Kenan Malik in Pandaemonium:

Officials eyeing you with contempt. Police treating you as scum. A sense of being constantly watched and judged by professionals. Living in fear of benefit sanctions. A lack of community facilities.

Officials eyeing you with contempt. Police treating you as scum. A sense of being constantly watched and judged by professionals. Living in fear of benefit sanctions. A lack of community facilities.

Such is likely to be your experience if you are working class. Such is also likely to be your experience if you are of black or minority ethnic origin.

But here’s the odd thing: people from the working class and minorities are rarely seen as facing the same kinds of issues. Instead, in political debates from Brexit to welfare benefits, minorities and the working class are seen as having conflicting interests and often set against each other. We are Ghosts: Race, Class and Institutional Prejudice, a report published last week by the thinktanks Class and the Runnymede Trust, attempts to address this this issue of common experiences yet conflicting perceived interests. Based on interviews and focus groups, almost entirely in London, the sample may not be statistically valid but the subjective experiences of the interviewees are revealing.

More here.

W

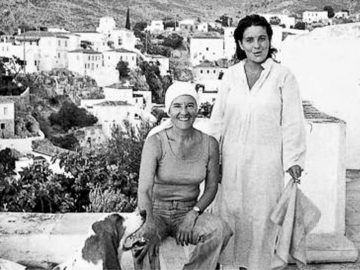

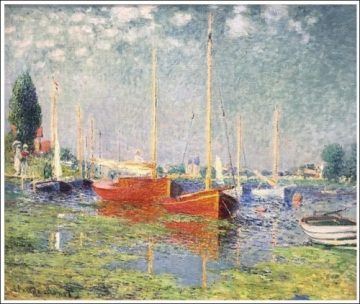

W “That summer we bought big straw hats. Maria’s had cherries around the rim, Infanta’s had forget-me-nots, and mine had poppies as red as fire. When we lay in the hayfield wearing them, the sky, the wildflowers, and the three of us all melted into one.” The beginning of Margarita Liberaki’s Three Summers, at once vivid and hazy, evokes the season and the story of adolescent girlhood that the book will unfold. The novel tells the story of three sisters living outside Athens: Maria, Infanta, and Katerina, the youngest, who tells the tale. The house where they live with their mother, aunt, and grandfather is in the countryside. Focusing on the sisters’ daily life and first loves, as well as on a secret about their Polish grandmother, the novel is about growing up and how strange and exciting it is to discover the curious moods and desires that constitute you and your difference from other people. It also features a stable cast of friends and neighbors, all with their own unexpected opinions: the self-involved Laura Parigori; the studious astronomer David and his Jewish mother, Ruth, from England; and the carefree Captain Andreas. The book is adventurous, fantastical, romantic, down to earth, earthy, and, above all, warm. Its only season, after all, is summer.

“That summer we bought big straw hats. Maria’s had cherries around the rim, Infanta’s had forget-me-nots, and mine had poppies as red as fire. When we lay in the hayfield wearing them, the sky, the wildflowers, and the three of us all melted into one.” The beginning of Margarita Liberaki’s Three Summers, at once vivid and hazy, evokes the season and the story of adolescent girlhood that the book will unfold. The novel tells the story of three sisters living outside Athens: Maria, Infanta, and Katerina, the youngest, who tells the tale. The house where they live with their mother, aunt, and grandfather is in the countryside. Focusing on the sisters’ daily life and first loves, as well as on a secret about their Polish grandmother, the novel is about growing up and how strange and exciting it is to discover the curious moods and desires that constitute you and your difference from other people. It also features a stable cast of friends and neighbors, all with their own unexpected opinions: the self-involved Laura Parigori; the studious astronomer David and his Jewish mother, Ruth, from England; and the carefree Captain Andreas. The book is adventurous, fantastical, romantic, down to earth, earthy, and, above all, warm. Its only season, after all, is summer. Many poets

Many poets Nothing belongs to us any more; they have taken away our clothes, our shoes, even our hair; if we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listen, they will not understand. They will even take away our name: and if we want to keep it, we will have to find our strength to do so, to manage somehow so that behind the name something of us, of us as we were, still remains.” So

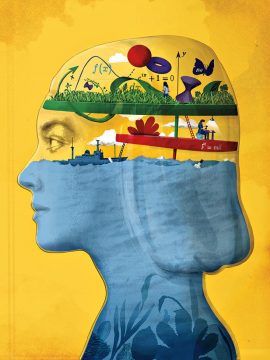

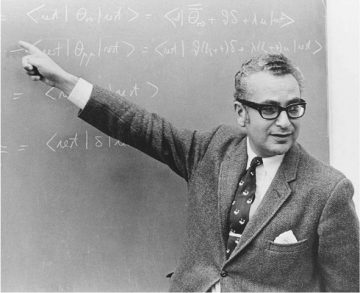

Nothing belongs to us any more; they have taken away our clothes, our shoes, even our hair; if we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listen, they will not understand. They will even take away our name: and if we want to keep it, we will have to find our strength to do so, to manage somehow so that behind the name something of us, of us as we were, still remains.” So  I was a wayward kid who grew up on the literary side of life, treating math and science as if they were pustules from the plague. So it’s a little strange how I’ve ended up now—someone who dances daily with triple integrals, Fourier transforms, and that crown jewel of mathematics, Euler’s equation. It’s hard to believe I’ve flipped from a virtually congenital math-phobe to a professor of engineering. One day, one of my students asked me how I did it—how I changed my brain. I wanted to answer Hell—with lots of difficulty! After all, I’d flunked my way through elementary, middle, and high school math and science. In fact, I didn’t start studying remedial math until I left the Army at age 26. If there were a textbook example of the potential for adult neural plasticity, I’d be Exhibit A.

I was a wayward kid who grew up on the literary side of life, treating math and science as if they were pustules from the plague. So it’s a little strange how I’ve ended up now—someone who dances daily with triple integrals, Fourier transforms, and that crown jewel of mathematics, Euler’s equation. It’s hard to believe I’ve flipped from a virtually congenital math-phobe to a professor of engineering. One day, one of my students asked me how I did it—how I changed my brain. I wanted to answer Hell—with lots of difficulty! After all, I’d flunked my way through elementary, middle, and high school math and science. In fact, I didn’t start studying remedial math until I left the Army at age 26. If there were a textbook example of the potential for adult neural plasticity, I’d be Exhibit A.

This genetic explanation of my Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry came as no surprise. According to family lore, my forebears lived in small towns and villages in eastern Europe for at least a few hundred years, where they kept their traditions and married within the community, up until the Holocaust, when they were either murdered or dispersed.

This genetic explanation of my Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry came as no surprise. According to family lore, my forebears lived in small towns and villages in eastern Europe for at least a few hundred years, where they kept their traditions and married within the community, up until the Holocaust, when they were either murdered or dispersed.

Almost all books of aphorisms, which have ever acquired a reputation, have retained it,” John Stuart Mill wrote in 1837, aphoristically—that is to say, with a neat if slightly dubious finality. (“How wofully the reverse is the case with systems of philosophy,” he added.) We prefer collections of aphorisms over big books of philosophy, Mill thought, not just because the contents are always short and usually funny but because the aphorism is, in its algebraic abbreviation, a micro-model of empirical inquiry. Mill noted that “to be unsystematic is of the essence of all truths which rest on specific experiment,” and that there is, in a good aphorism, “generally truth, or a bold approach to some truth.” So when La Rochefoucauld writes, “In the misfortune of even our best friends, there is something that does not displease us,” he is offering not a moral injunction saying “Take pleasure in the misfortune of your best friends” but a testable observation about what Mill termed “the workings of habitual selfishness in the human breast.” The aphorism means: We do take pleasure—not in every case, perhaps, but more often than we might admit—in the misfortune of our best friends.

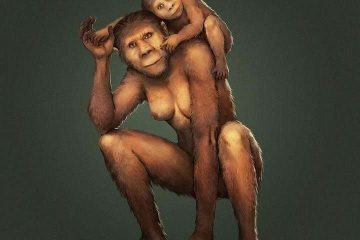

Almost all books of aphorisms, which have ever acquired a reputation, have retained it,” John Stuart Mill wrote in 1837, aphoristically—that is to say, with a neat if slightly dubious finality. (“How wofully the reverse is the case with systems of philosophy,” he added.) We prefer collections of aphorisms over big books of philosophy, Mill thought, not just because the contents are always short and usually funny but because the aphorism is, in its algebraic abbreviation, a micro-model of empirical inquiry. Mill noted that “to be unsystematic is of the essence of all truths which rest on specific experiment,” and that there is, in a good aphorism, “generally truth, or a bold approach to some truth.” So when La Rochefoucauld writes, “In the misfortune of even our best friends, there is something that does not displease us,” he is offering not a moral injunction saying “Take pleasure in the misfortune of your best friends” but a testable observation about what Mill termed “the workings of habitual selfishness in the human breast.” The aphorism means: We do take pleasure—not in every case, perhaps, but more often than we might admit—in the misfortune of our best friends. Extended parental care is considered one of the hallmarks of human evolution. A stunning new research result published today in Nature reveals for the first time the parenting habits of one of our earliest extinct ancestors.

Extended parental care is considered one of the hallmarks of human evolution. A stunning new research result published today in Nature reveals for the first time the parenting habits of one of our earliest extinct ancestors.

It does not take long for history to repeat itself. It was only a little over a decade ago that overzealous lending, lax underwriting standards, unrealistic collateral valuations, borrowers not understanding loan terms, an exploding derivative securities market–and a dozen or so other factors–led to a massive crash in the housing market. Today in the United States we have outstanding student loan debt of $1.5

It does not take long for history to repeat itself. It was only a little over a decade ago that overzealous lending, lax underwriting standards, unrealistic collateral valuations, borrowers not understanding loan terms, an exploding derivative securities market–and a dozen or so other factors–led to a massive crash in the housing market. Today in the United States we have outstanding student loan debt of $1.5

While Trump’s immigration politics makes international headlines almost every day, the disaster of the European immigration policies rarely becomes international news. A recent exception is the case of Captain Carola Rackete, and it is a telling one. With all the potential for a good story, Rackete’s journey is both standing for and at the same time distracting from the actual complex mess of European immigration politics.

While Trump’s immigration politics makes international headlines almost every day, the disaster of the European immigration policies rarely becomes international news. A recent exception is the case of Captain Carola Rackete, and it is a telling one. With all the potential for a good story, Rackete’s journey is both standing for and at the same time distracting from the actual complex mess of European immigration politics. When the flight delay is announced, we ask what it is we have done wrong. From airlines and the world at large, the answer is rarely forthcoming, so we must look inward instead.

When the flight delay is announced, we ask what it is we have done wrong. From airlines and the world at large, the answer is rarely forthcoming, so we must look inward instead.