Month: July 2019

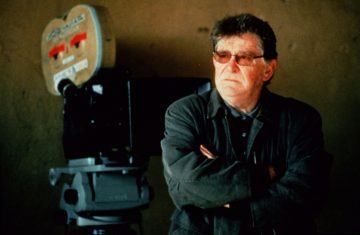

Two Films by Ermanno Olmi

Griffin Oleynick at Commonweal:

Legend of the Holy Drinker introduces viewers to Olmi’s mature understanding of the economy of grace and the price of salvation. Adapted from a novella by Austrian writer Joseph Roth, the film tells the tragic story of Andreas, a down-and-out middle-aged man living under the bridges of modern Paris. The plot unfolds like a medieval hagiography, replete with chance encounters and sudden (often comical) twists of fortune. Events are set in motion by the unbidden appearance of a kind stranger, a recent convert to Catholicism and devotee of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, who offers Andreas the handsome sum of two hundred francs to help him get back on his feet. There’s a catch, though; the stranger gently requests that Andreas eventually return the money as a holy offering before the saint’s statue, housed in the Church of Sainte-Marie des Batignolles. Andreas, “a man of honor,” readily agrees. But week after week Andreas fails to fulfill his vow, as a series of old acquaintances (and copious carafes of wine) prevent him from making his way to Mass every Sunday.

Legend of the Holy Drinker introduces viewers to Olmi’s mature understanding of the economy of grace and the price of salvation. Adapted from a novella by Austrian writer Joseph Roth, the film tells the tragic story of Andreas, a down-and-out middle-aged man living under the bridges of modern Paris. The plot unfolds like a medieval hagiography, replete with chance encounters and sudden (often comical) twists of fortune. Events are set in motion by the unbidden appearance of a kind stranger, a recent convert to Catholicism and devotee of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, who offers Andreas the handsome sum of two hundred francs to help him get back on his feet. There’s a catch, though; the stranger gently requests that Andreas eventually return the money as a holy offering before the saint’s statue, housed in the Church of Sainte-Marie des Batignolles. Andreas, “a man of honor,” readily agrees. But week after week Andreas fails to fulfill his vow, as a series of old acquaintances (and copious carafes of wine) prevent him from making his way to Mass every Sunday.

more here.

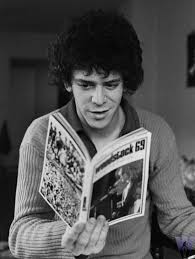

Literary Lou Reed

Matt Hanson at The Millions:

What made Reed’s songs special went beyond his notorious obsession with decadence, his caustic dry wit, and his sneaky romantic vulnerability. He was also one of the most literate of musicians and wasn’t shy about making his literary influences known. As a college kid, he was mentored by the brilliantly mad poet and critic Delmore Schwartz and took inspiration from the likes of Raymond Chandler, William S. Burroughs, James Joyce, Shakespeare, and Poe. Lulu, his odd later-period collaboration with Metallica, is perhaps best passed over—but basing a metal record on a 19th-century Austrian play is something very few writers would have even imagined, let alone attempted. Reed brought an informed, sophisticated writer’s eye to the kinds of underworlds he inhabited and observed, and his sense of language was as keen as a journalist’s. Reed made sure all the who, where, what, how, why bases got covered, using his own laconic, inimitable language.

What made Reed’s songs special went beyond his notorious obsession with decadence, his caustic dry wit, and his sneaky romantic vulnerability. He was also one of the most literate of musicians and wasn’t shy about making his literary influences known. As a college kid, he was mentored by the brilliantly mad poet and critic Delmore Schwartz and took inspiration from the likes of Raymond Chandler, William S. Burroughs, James Joyce, Shakespeare, and Poe. Lulu, his odd later-period collaboration with Metallica, is perhaps best passed over—but basing a metal record on a 19th-century Austrian play is something very few writers would have even imagined, let alone attempted. Reed brought an informed, sophisticated writer’s eye to the kinds of underworlds he inhabited and observed, and his sense of language was as keen as a journalist’s. Reed made sure all the who, where, what, how, why bases got covered, using his own laconic, inimitable language.

more here.

Our Love of The Minuscule

Leslie Jamison at the TLS:

Stewart is particularly good on the double-edged quality of the miniature. She grasps that the doll’s house is both paradise and cloister, for example, that it “represents a particular form of interiority, an interiority which the subject experiences as its sanctuary (fantasy) and prison”. She argues that the miniature always presents something that has already been lost, that you can never quite touch: “a world whose anteriority is always absolute, and whose profound interiority is therefore always unrecoverable”. While it can be tempting to focus on miniatures as fulfilments of fantasy, as Garfield does, Stewart asks us to read them as promises that are perpetually broken, as sites of unresolved longing. Miniatures are more like excursions than journeys, she argues, because you always have to come back from the fantasy. You can never stay for good. I’d argue that you can’t even really go in the first place: as with the shrinking man of Bekonscot, entering the miniature landscape means losing the very thing that makes it magical.

Stewart is particularly good on the double-edged quality of the miniature. She grasps that the doll’s house is both paradise and cloister, for example, that it “represents a particular form of interiority, an interiority which the subject experiences as its sanctuary (fantasy) and prison”. She argues that the miniature always presents something that has already been lost, that you can never quite touch: “a world whose anteriority is always absolute, and whose profound interiority is therefore always unrecoverable”. While it can be tempting to focus on miniatures as fulfilments of fantasy, as Garfield does, Stewart asks us to read them as promises that are perpetually broken, as sites of unresolved longing. Miniatures are more like excursions than journeys, she argues, because you always have to come back from the fantasy. You can never stay for good. I’d argue that you can’t even really go in the first place: as with the shrinking man of Bekonscot, entering the miniature landscape means losing the very thing that makes it magical.

more here.

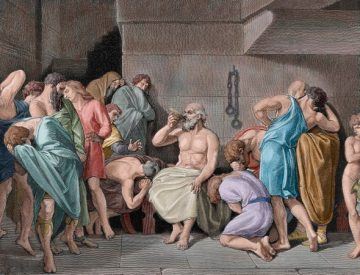

Socrates’ Critique of 21st-Century Neuroscience

Daniel Silvermintz in Scientific American:

If chocolate releases the same chemicals in the brain as sexual excitement, why not forgo the trials and tribulations of a romantic relationship for a bowl of Hershey’s kisses. Twenty-first century neuroscience provides such a sophisticated understanding of brain functions that it is tempting to mistake the psychic mechanism with the ultimate goal. This is precisely what goes on in the field of psychobiology, which eschews discussion of meaning beyond the biological process. Ironically, the scientific study of psychology was initiated by Socrates’ disillusionment with the natural sciences in light of their complete inability to account for human behavior. Alongside advances in brain science, we need to rediscover the ancient approach to behavioral science as a means of restoring meaning to function, if for no other reason than that our lives depend on it.

If chocolate releases the same chemicals in the brain as sexual excitement, why not forgo the trials and tribulations of a romantic relationship for a bowl of Hershey’s kisses. Twenty-first century neuroscience provides such a sophisticated understanding of brain functions that it is tempting to mistake the psychic mechanism with the ultimate goal. This is precisely what goes on in the field of psychobiology, which eschews discussion of meaning beyond the biological process. Ironically, the scientific study of psychology was initiated by Socrates’ disillusionment with the natural sciences in light of their complete inability to account for human behavior. Alongside advances in brain science, we need to rediscover the ancient approach to behavioral science as a means of restoring meaning to function, if for no other reason than that our lives depend on it.

…For Socrates, the misapplication of the natural sciences to human affairs renders the investigator incapable of seeing such fundamental notions as justice, beauty and goodness since they lack a material explanation. He poignantly illustrates the fallacy of scientific reasoning by considering how a biologist would explain why Socrates is sitting in his prison cell: “The bones are hung loose in their ligaments, the sinews, by relaxing and contracting, make me able to bend my limbs now,” declares Socrates just before drinking the poison, “and that is the cause of my sitting here with my legs bent.” Of course, one cannot argue with the truth of the biologist’s explanation; nonetheless, bones and sinews have nothing to do with why Socrates is sitting on death row.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Being out West When Time Stood Still

Once she had a seamless mind.

Clouds rolled into her thinking

like opposites attracting. And hitching.

There was that openness of beginning.

Those crisp little white cockle shells. And then

that low fog. Spreading around

like when once you could touch time without rules or referees,

like when you used to dance alone with your eyes closed

serenading crazy in your room late, doors shut, the music on fire,

and you moved around in there, bumping the walls

like salmon swarming and flopping up the ladder.

Just that. Somehow just

to be seamless that way. Fiercely in the free.

Clouding in open fog.

by Linda E. Chown

from Numéro Cinq

Vol. VIII, No. 7, July 2017

Six Degrees of Separation at Burning Man

Epstein et al in Nautilus:

Today the alkaline desert is quiet. The roar of techno music and flamethrowers has been replaced with the soft clink of rakes and trash cans. Thousands of people put aside their hangovers to methodically clean the desert. After a dedicated communal cleaning, Burning Man, one of the largest arts events in the world, spanning seven days and involving over 70,000 participants, leaves not a single wrapper on the desert. Among the swarm of salt-crusted denizens of this ephemeral city (known as Burners) is us: a scientist who studies cooperation, an industrial designer, and a Silicon Valley security CEO. Among the dismantled rigs, lifeless pyrotechnics, and bowed heads of Burners absorbed in cleaning, we are here trying to answer a simple question: How, after so many years, could Burning Man throw an event of such chaos, and yet leave the desert without a trace? What leads thousands of people in such an extreme environment to consistently engage in cooperative behavior at a scale seldom seen in society?

Today the alkaline desert is quiet. The roar of techno music and flamethrowers has been replaced with the soft clink of rakes and trash cans. Thousands of people put aside their hangovers to methodically clean the desert. After a dedicated communal cleaning, Burning Man, one of the largest arts events in the world, spanning seven days and involving over 70,000 participants, leaves not a single wrapper on the desert. Among the swarm of salt-crusted denizens of this ephemeral city (known as Burners) is us: a scientist who studies cooperation, an industrial designer, and a Silicon Valley security CEO. Among the dismantled rigs, lifeless pyrotechnics, and bowed heads of Burners absorbed in cleaning, we are here trying to answer a simple question: How, after so many years, could Burning Man throw an event of such chaos, and yet leave the desert without a trace? What leads thousands of people in such an extreme environment to consistently engage in cooperative behavior at a scale seldom seen in society?

To answer that question, we must start our journey at the MIT Media Lab, in an aptly named research group: Scalable Cooperation. This group studies how technologies—social media, the Internet, artificial intelligence—can empower cooperative human networks. The group’s heritage includes the scientists who solved DARPA’s Red Balloon Challenge in 2008, in which the United States government scattered 10 red weather balloons across the continental U.S., and instructed teams of researchers to locate them as fast as possible. The winning MIT team found all 10 balloons in just under nine hours using the virality of social media and an incentive structure that motivated people to recruit their friends. This result was a resounding success for crowdsourcing and the Internet at large, demonstrating that a collective of individuals, connected through technology, could together solve large-scale problems that no individual could solve alone.

More here.

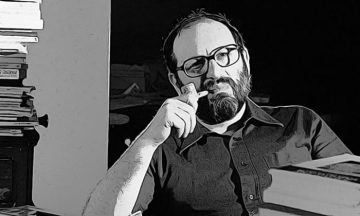

How to Write a Thesis, According to Umberto Eco

From the MIT Press Reader:

You are not Proust. Do not write long sentences. If they come into your head, write them, but then break them down. Do not be afraid to repeat the subject twice, and stay away from too many pronouns and subordinate clauses. Do not write,

You are not Proust. Do not write long sentences. If they come into your head, write them, but then break them down. Do not be afraid to repeat the subject twice, and stay away from too many pronouns and subordinate clauses. Do not write,

The pianist Wittgenstein, brother of the well-known philosopher who wrote the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicusthat today many consider the masterpiece of contemporary philosophy, happened to have Ravel write for him a concerto for the left hand, since he had lost the right one in the war.

Write instead,

The pianist Paul Wittgenstein was the brother of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Since Paul was maimed of his right hand, the composer Maurice Ravel wrote a concerto for him that required only the left hand.

More here.

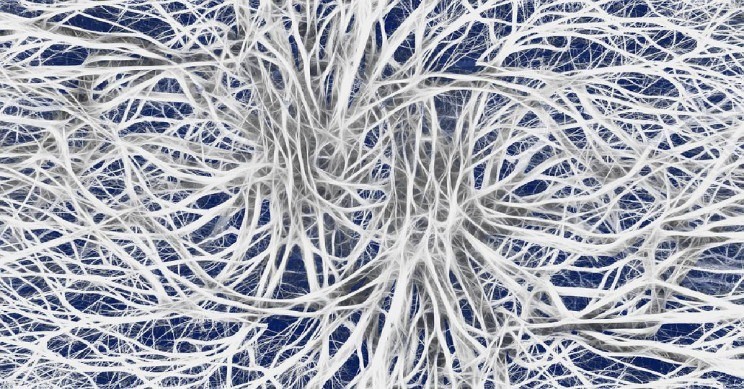

Scientists Map out the Entire Neural Wiring of an Animal’s Nervous System

Fabienne Lang in Interesting Engineering:

Scientists at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine have put together the complete wiring diagram of the nervous system of an animal.

Scientists at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine have put together the complete wiring diagram of the nervous system of an animal.

In the study, the researchers focused on the roundworm called Caenorhabditis elegans or C. elegans’s brains, and have discovered a few differences between the male and female of the species.

By putting together the map of the nervous system, the research assists in understanding nerve connections (thus where the term “connectomics” stems from) which are responsible for different human and animal behaviors.

Dr. Scott Emmons, the study’s lead author and professor of Genetics in the Dominick P. Purpura Department of Neuroscience, said, “Structure is always central to biology. The structure of the DNA revealed how genes work, and the structure of proteins revealed how enzymes function. Now, the structure of the nervous system is revealing how animals behave and how neural connections go wrong because of disease.”

More here.

Economics Is Broken

Annika Neklason in The Atlantic:

For years, the government of Bhutan has enshrined gross national happiness as its guiding light. Though national leaders had long eschewed traditional economic metrics like gross domestic product in favor of a more subjective understanding of development, in 2008, the country’s constitution formally established that ensuring “a good quality of life for the people of Bhutan” would be its primary aim. GNH would be the measure of the country’s progress, quantified by a complicated index based on “areas of psychological well being, cultural diversity and resilience, education, health, time use, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity and resilience and economic living standards”—an array of factors that might all together quantify well-being and happiness.

The United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution in 2011 that praised Bhutan’s efforts. It also recognized that “the gross domestic product indicator by nature was not designed to and does not adequately reflect the happiness and well-being of people in a country” and that “a more inclusive, equitable and balanced approach to economic growth that promotes sustainable development, poverty eradication, happiness and well-being of all peoples” was needed.

Gene Sperling, who served as an economic adviser to Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama and frequently contributes to The Atlantic, has come to the same conclusion.

More here.

Decolonising Philosophy: Do we need to wake up to western prejudice?

The Inescapable Town Square

L. M. Sacasas at The New Atlantis:

At the heart of Ong’s analysis is the understanding that each major transition in media technology — that is, in the means of communication — transformed or restructured human consciousness and human society. “Technologies are not mere exterior aids,” Ong explains, “but also interior transformations of consciousness, and never more than when they affect the word.” Literate society was not simply the old society of primary orality with the added advantage of writing, but in many respects a new society. The advent of electronic media was similarly consequential, inaugurating what we think of as the age of mass media in the twentieth century. Now we find ourselves thrust into an era dominated by the effects of digital media. We can’t yet know the full ramifications of this transition, but, taking a cue from some of Ong’s insights, we can begin to make some pertinent observations, particularly with respect to the character of digital discourse.

At the heart of Ong’s analysis is the understanding that each major transition in media technology — that is, in the means of communication — transformed or restructured human consciousness and human society. “Technologies are not mere exterior aids,” Ong explains, “but also interior transformations of consciousness, and never more than when they affect the word.” Literate society was not simply the old society of primary orality with the added advantage of writing, but in many respects a new society. The advent of electronic media was similarly consequential, inaugurating what we think of as the age of mass media in the twentieth century. Now we find ourselves thrust into an era dominated by the effects of digital media. We can’t yet know the full ramifications of this transition, but, taking a cue from some of Ong’s insights, we can begin to make some pertinent observations, particularly with respect to the character of digital discourse.

more here.

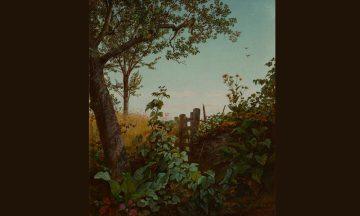

On The American Pre-Raphaelites

Bailey Trela at the LARB:

The painting that kicked it all off, Ruskin’s own Fragment of the Alps, goes a long way towards explaining the intermingling of spirituality and scientific exactitude found in the best of the American Pre-Raphaelites’ works. Shuttled around America in a touring exhibition in the year 1857, the small canvas is a fantasia of vivid yellows and saturated purples, yet this almost surreal medley stems from no more mystical source than Ruskin’s hidebound attention to the play of light on stone. As the exhibition notes make clear, the careful delineation of the natural environment was a profoundly moral act for Ruskin. Detail became a form of prayer, a sort of thanksgiving for and hymn to God’s creation. The delicate plexing of boughs in Charles Herbert Moore’s Pine Tree, from 1868, are a perfect non-Ruskinian example of this drive — the detail is so fine that the tree seems to be melting upward, the fine pen markings gradually being blown away by the wind.

The painting that kicked it all off, Ruskin’s own Fragment of the Alps, goes a long way towards explaining the intermingling of spirituality and scientific exactitude found in the best of the American Pre-Raphaelites’ works. Shuttled around America in a touring exhibition in the year 1857, the small canvas is a fantasia of vivid yellows and saturated purples, yet this almost surreal medley stems from no more mystical source than Ruskin’s hidebound attention to the play of light on stone. As the exhibition notes make clear, the careful delineation of the natural environment was a profoundly moral act for Ruskin. Detail became a form of prayer, a sort of thanksgiving for and hymn to God’s creation. The delicate plexing of boughs in Charles Herbert Moore’s Pine Tree, from 1868, are a perfect non-Ruskinian example of this drive — the detail is so fine that the tree seems to be melting upward, the fine pen markings gradually being blown away by the wind.

more here.

The Last Poems of James Tate

Dan Chiasson at The New Yorker:

Tate’s final work will lodge him permanently in the landscape of American poetry, but, like Dickinson, he will always also be a local phenomenon. In 2004, he published a poem, “Of Whom Am I Afraid?,” about encountering “an old grizzled farmer” at the supply store. They strike up a conversation about Dickinson’s poetry. (It may seem unlikely, or “Surreal,” but Amherst has always had its share of literary farmers.) These two men discuss Dickinson’s toughness; then the farmer, testing Tate’s own mettle, slaps him across the face. Somehow this is a form of homage, and Tate commemorates the occasion by buying “some ice tongs . . . for which I had no earthly use.” They wind up, instead, in a poem. It’s that higher utility that Tate always sought.

Tate’s final work will lodge him permanently in the landscape of American poetry, but, like Dickinson, he will always also be a local phenomenon. In 2004, he published a poem, “Of Whom Am I Afraid?,” about encountering “an old grizzled farmer” at the supply store. They strike up a conversation about Dickinson’s poetry. (It may seem unlikely, or “Surreal,” but Amherst has always had its share of literary farmers.) These two men discuss Dickinson’s toughness; then the farmer, testing Tate’s own mettle, slaps him across the face. Somehow this is a form of homage, and Tate commemorates the occasion by buying “some ice tongs . . . for which I had no earthly use.” They wind up, instead, in a poem. It’s that higher utility that Tate always sought.

more here.

Here’s why busy-ness is so damaging

Jackie Smith and Joyce Dalsheim in AlterNet:

There never seems to be enough time to accomplish all the things we must do. Life gets busier and busier. But what does all that busy-ness add to our lives? Mainstream culture tells us that being busy is a virtue, so we want to be busy even if we complain about it. It means we’re productive and have purpose. Ideas like “time is money” and “idle hands are the devil’s workshop” have helped to define our culture. Both ideas work in concert with the global capitalist economy, which depends on keeping us busy in order to increase productivity, expand markets, and encourage hyper-consumption. Busy-ness also helps to keep us from questioning the assumptions and values that drive busy-ness itself. Busy-ness is part of a broader set of structures that limit our choices and our ability to feel satisfied. What we call the “hegemony of busy-ness” refers two interrelated processes. First, busyness is a powerful cultural pressure. Second, and more importantly, this busy-ness perpetuates the social system that makes the rich richer and creates more and more economically vulnerable people. We are impelled to do more and to want to do more, but busy-ness limits our ability to improve our overall happiness, promote greater equity, or save our endangered planet.

There never seems to be enough time to accomplish all the things we must do. Life gets busier and busier. But what does all that busy-ness add to our lives? Mainstream culture tells us that being busy is a virtue, so we want to be busy even if we complain about it. It means we’re productive and have purpose. Ideas like “time is money” and “idle hands are the devil’s workshop” have helped to define our culture. Both ideas work in concert with the global capitalist economy, which depends on keeping us busy in order to increase productivity, expand markets, and encourage hyper-consumption. Busy-ness also helps to keep us from questioning the assumptions and values that drive busy-ness itself. Busy-ness is part of a broader set of structures that limit our choices and our ability to feel satisfied. What we call the “hegemony of busy-ness” refers two interrelated processes. First, busyness is a powerful cultural pressure. Second, and more importantly, this busy-ness perpetuates the social system that makes the rich richer and creates more and more economically vulnerable people. We are impelled to do more and to want to do more, but busy-ness limits our ability to improve our overall happiness, promote greater equity, or save our endangered planet.

Our global economic and political order fuels a state of constant activity, and busy-ness harms both individual and community well-being. There’s so much information thrown at us, we just don’t know where to start. Time poverty limits our ability to talk with neighbors and nurture communities. If time is money for some, it is also what gives meaning to our lives. Busy-ness disconnects us from our social habitats by preoccupying us with endless tasks and often meaningless information.

The upshot is that busy-ness undermines our physical and mental health as well as our ability to think and learn. Modern society has transformed homo sapiens into what former technology professional and Consciously Digital founder Anastasia Dedyukhina calls homo distractus -people who are continuously inundated with information and perpetually distracted.

More here.

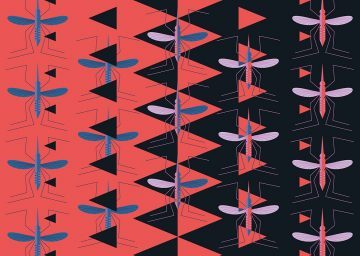

Self-destructing mosquitoes and sterilized rodents: the promise of gene drives

Megan Scudellari in Nature:

Austin Burt and Andrea Crisanti had been trying for eight years to hijack the mosquito genome. They wanted to bypass natural selection and plug in a gene that would mushroom through the population faster than a mutation handed down by the usual process of inheritance. In the back of their minds was a way to prevent malaria by spreading a gene to knock out mosquito populations so that they cannot transmit the disease. Crisanti remembers failing over and over. But finally, in 2011, the two geneticists at Imperial College London got back the DNA results they’d been hoping for: a gene they had inserted into the mosquito genome had radiated through the population, reaching more than 85% of the insects’ descendants1.

Austin Burt and Andrea Crisanti had been trying for eight years to hijack the mosquito genome. They wanted to bypass natural selection and plug in a gene that would mushroom through the population faster than a mutation handed down by the usual process of inheritance. In the back of their minds was a way to prevent malaria by spreading a gene to knock out mosquito populations so that they cannot transmit the disease. Crisanti remembers failing over and over. But finally, in 2011, the two geneticists at Imperial College London got back the DNA results they’d been hoping for: a gene they had inserted into the mosquito genome had radiated through the population, reaching more than 85% of the insects’ descendants1.

It was the first engineered ‘gene drive’: a genetic modification designed to spread through a population at higher-than-normal rates of inheritance. Gene drives have rapidly become a routine technology in some laboratories; scientists can now whip up a drive in months. The technique relies on the gene-editing tool CRISPR and some bits of RNA to alter or silence a specific gene, or insert a new one. In the next generation, the whole drive copies itself onto its partner chromosome so that the genome no longer has the natural version of the chosen gene, and instead has two copies of the gene drive. In this way, the change is passed on to up to 100% of offspring, rather than around 50% (see ‘How gene drives work’).

More here.

‘In India, it’s pathological authoritarianism’ —Akeel Bilgrami

Jipson John and Jitheesh P. M. in Frontline:

You have pointed out the role of liberalism in keeping out the New Deal and the social democratic ideals of [Bernie] Sanders and [Jeremy] Corbyn. And you were highly critical of liberalism for that reason. You also said that liberalism is ensuring that nothing in the political arena is conceptually available for a fundamental transformation of society. But you are not equating social democracy with a fundamental transformation of society, are you? We know, from your writings, that you believe that social democracy does not amount to a radical critique of capitalism. So, then, can you explain what you have in mind exactly?

That raises a whole range of very familiar and long-standing issues that have afflicted the Left, leading to debates in India (and no doubt in other places as well) between the organised Left and what has come to be called the “ultra-Left” and the insurgent Left.

That raises a whole range of very familiar and long-standing issues that have afflicted the Left, leading to debates in India (and no doubt in other places as well) between the organised Left and what has come to be called the “ultra-Left” and the insurgent Left.

I think that what is true and what everybody knows is that liberalism in the 20th century has, as I’ve put it in some of my writing, “taken social democracy in its stride”, that is, taken in its stride the social-democratic constraints that had been put on capitalism after the end of the Second World War. But the point of the expression “take in its stride” should not be seen as merely saying that liberalism is able to accommodate these constraints in its doctrinal framework because they don’t constitute a fundamental critique of capitalism. What more is connoted by “take in its stride” is very important, in fact absolutely crucial, in understanding capitalism today and the ideological role of liberalism and the exact nature of the accommodation.

So, what would be this “more” you would add to the nature of the accommodation?

It is this. Liberalism takes social democracy in its stride not only by accommodating social democracy but also by making sure that the accommodation is always constantly being undermined, even as it is allowed to be there. In other words, social democracy should not be allowed an equilibrium (leave alone strengthening) within its accommodated status. That is the point of liberalism and it recurs everywhere. Even the Scandinavian countries are subject to it, though, of course, being more peripheral than the main belt of capitalism, social democracy there has not been so recurrently subject to this disequilibrium and instability in its status as in other parts of the capitalist world. So, when one says liberalism accommodates social democracy, we must be absolutely clear that that accommodation is never stable and is never going to be allowed to be stable.

More here. The first part of this two-part interview can be found here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Indre Viskontas on Music and the Brain

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

It doesn’t mean much to say music affects your brain — everything that happens to you affects your brain. But music affects your brain in certain specific ways, from changing our mood to helping us learn. As both a neuroscientist and an opera singer, Indre Viskontas is the ideal person to talk about the relationship between music and the brain. Her new book, How Music Can Make You Better, digs into why we love music, how it can unite and divide us, and how music has a special impact on the very young and the very old.

It doesn’t mean much to say music affects your brain — everything that happens to you affects your brain. But music affects your brain in certain specific ways, from changing our mood to helping us learn. As both a neuroscientist and an opera singer, Indre Viskontas is the ideal person to talk about the relationship between music and the brain. Her new book, How Music Can Make You Better, digs into why we love music, how it can unite and divide us, and how music has a special impact on the very young and the very old.

More here.

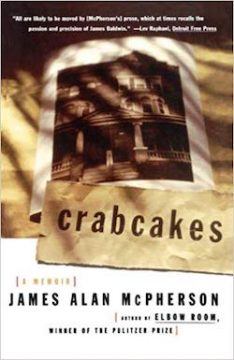

Before Ta-Nehisi Coates: On James Alan McPherson’s “Crabcakes”

Anya Ventura in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

JAMES ALAN MCPHERSON’S memoir Crabcakes begins with the death of his tenant, Mrs. Channie Washington. A traditional memoir might have sketched McPherson’s upbringing: the strapped childhood in segregated Savannah, Georgia, as the son of an electrician and a maid, and his ascent to Harvard Law School in the late ’60s. He might have noted that during that time, his short story “Gold Coast” won a competition sponsored by The Atlantic, and that two years later, with the story collection Hue and Cry already under his belt, he received his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He could have also mentioned that his second collection Elbow Room, published in 1977, earned him a Pulitzer Prize: the first African American to win one for fiction.

JAMES ALAN MCPHERSON’S memoir Crabcakes begins with the death of his tenant, Mrs. Channie Washington. A traditional memoir might have sketched McPherson’s upbringing: the strapped childhood in segregated Savannah, Georgia, as the son of an electrician and a maid, and his ascent to Harvard Law School in the late ’60s. He might have noted that during that time, his short story “Gold Coast” won a competition sponsored by The Atlantic, and that two years later, with the story collection Hue and Cry already under his belt, he received his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He could have also mentioned that his second collection Elbow Room, published in 1977, earned him a Pulitzer Prize: the first African American to win one for fiction.

In 1981, McPherson was among the first to be awarded a MacArthur “genius” grant. A different kind of narrative might have illuminated all these facts — a true Horatio Alger story — yet McPherson includes none, nor does he elaborate his pains (to the dismay of early critics, who grappled with this absence of biographic detail). Instead, in courteous and precise prose, he begins with Mrs. Washington.

More here.