by Eric J. Weiner

From Saint Pélagie Prison in 1883, Paul Lafargue wrote The Right to Be Lazy, an anti-capitalist polemic that challenged the hegemony of the “right to work” discourse. The focus of his outrage was the liberal elite as well as the proletarians. His central argument is summed up in this quote:

Capitalist ethics, a pitiful parody on Christian ethics, strikes with its anathema the flesh of the laborer; its ideal is to reduce the producer to the smallest number of needs, to suppress his joys and his passions and to condemn him to play the part of a machine turning out work without respite and without thanks.

Quite a bit has changed since he wrote his polemic, yet I think there are some important insights that still resonate in the 21st century. Unlike the industrialism that informed Lafargue’s critique of the bourgeoisie’s work fetish, time at work in the 21st century is no longer primarily experienced in the factory or small brick-and-mortar business. In today’s knowledge economy, we celebrate a form of “uber” work where workers “enjoy” the flexible benefits of constant connectivity, borderless geographies of work/time, and schedules unconstrained by days-of-week or time-of-day. Workdays blend into work-nights which slide into work-mornings without beginning or end. Not unlike techniques of “enhanced interrogation” that leverage the power of time to (dis)orient, in our current historical juncture time is erased leaving workers without a sense of place; there is nothing to distinguish Wednesday from Sunday, Monday from Friday. In this new timeless workscape, the old adage TGIF is meaningless, an artifact as quaint as the vinyl record or paper road maps. Within this environment, workers struggle to adapt to this new model. For example, people still claim to need more time, yet in the 21st century postmodern workscape, time no longer has a meaningful referent. It simply floats above labor signaling neither a beginning nor end. Clocks likewise have become a quaint, antiquated technology of a mechanical era, yet they are still ubiquitous in most work-spaces. In this new workscape, clocks don’t measure time in order to determine the value of one’s labor on an hourly, weekly, or annual calendar. For uber-workers, the clock never gets punched because it doesn’t really exist in the context of their flexible workscapes. At most, they can orient workers to meet up for lunch or for that rare occasion when a body-to-body meeting is desired (it rarely is). They also, in the form of a wrist watch, can represent a kind of retro-cool, a form of cultural capital, especially when the watch is an “automatic”!

Uber workers are “free” to take a break yet no one can or actually does because “taking a break” requires one to be at work somewhere, anywhere. Today’s uber-workforce has no indigenous location, no point of reference in time and space and therefore no recognizable beginning or end. Without this geography of labor, workers are always “on,” and never “off.” This constant state of work is then described as a form of freedom. Read more »

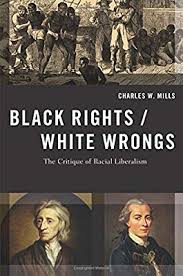

Charles Mills’s Black Rights/White Wrongs represents the culmination of more than two decades of work on the philosophy of race and social justice. Mills received his PhD from the University of Toronto in 1985, working with the left-wing philosophers Frank Cunningham and Daniel Goldstick on the concept of ideology in Marx and Engels. In the following years, liberal political philosophy would be strongly challenged. A growing number of feminists argued that liberal normative theorists were engaged in a form of selective historical imagination, erasing everyone but white males from the story of political society’s origins.

Charles Mills’s Black Rights/White Wrongs represents the culmination of more than two decades of work on the philosophy of race and social justice. Mills received his PhD from the University of Toronto in 1985, working with the left-wing philosophers Frank Cunningham and Daniel Goldstick on the concept of ideology in Marx and Engels. In the following years, liberal political philosophy would be strongly challenged. A growing number of feminists argued that liberal normative theorists were engaged in a form of selective historical imagination, erasing everyone but white males from the story of political society’s origins.

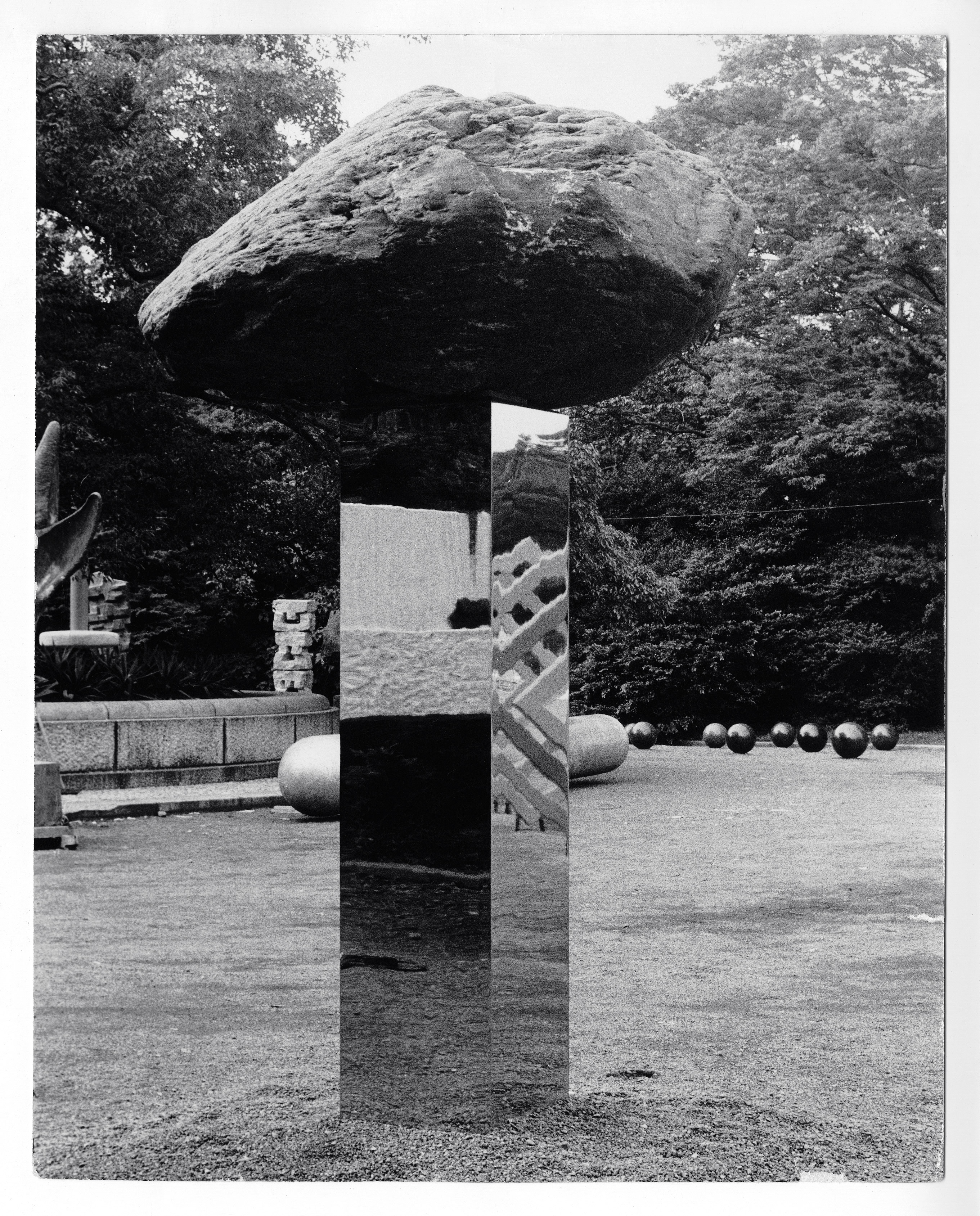

Pei’s stature among architects is hard to convey. However visually entertaining their work, the likely legacies of other American so-called starchitects shrink—some to triviality—beside the decades of modern design that Ieoh Ming Pei produced, from his earliest built work in 1948 to his last project sixty years later. By the time he co-designed the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha in 2008, he was among the last practicing students of a teacher from the Bauhaus. Walter Gropius taught, and later taught beside, Pei at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Gropius had arrived there in 1937. Pei, the scion of a Suzhou banking family who left Shanghai in 1935 for undergraduate study at Penn and MIT, arrived at Harvard in 1942. His classmates included Paul Rudolph and Philip Johnson.

Pei’s stature among architects is hard to convey. However visually entertaining their work, the likely legacies of other American so-called starchitects shrink—some to triviality—beside the decades of modern design that Ieoh Ming Pei produced, from his earliest built work in 1948 to his last project sixty years later. By the time he co-designed the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha in 2008, he was among the last practicing students of a teacher from the Bauhaus. Walter Gropius taught, and later taught beside, Pei at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Gropius had arrived there in 1937. Pei, the scion of a Suzhou banking family who left Shanghai in 1935 for undergraduate study at Penn and MIT, arrived at Harvard in 1942. His classmates included Paul Rudolph and Philip Johnson. Climate change is certainly an urgent challenge. Rising levels of greenhouse gases are raising temperatures worldwide, leading to shifting weather patterns that are only expected to get worse, with increased

Climate change is certainly an urgent challenge. Rising levels of greenhouse gases are raising temperatures worldwide, leading to shifting weather patterns that are only expected to get worse, with increased  John Bolton, White House national security adviser and notorious Iraq-era hawk, is a man on a mission. Given broad latitude over policy by Donald Trump, he is widely held to be driving the US confrontation with

John Bolton, White House national security adviser and notorious Iraq-era hawk, is a man on a mission. Given broad latitude over policy by Donald Trump, he is widely held to be driving the US confrontation with

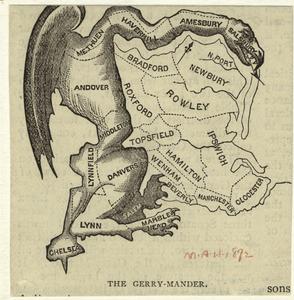

The Supreme Court doesn’t play politics.

The Supreme Court doesn’t play politics.

Several co-workers, all of whom have Ph.D.s. An old friend who’s a physicist. Scads of family members of both blue and white collar variety. Numerous neighbors. And of course the well dressed, kindly old women who occasionally show up at my door uninvited, pamphlets in hand.

Several co-workers, all of whom have Ph.D.s. An old friend who’s a physicist. Scads of family members of both blue and white collar variety. Numerous neighbors. And of course the well dressed, kindly old women who occasionally show up at my door uninvited, pamphlets in hand.

Johnny spoke softly in a voice just past the threshold of manhood. His smile, mistaken for charm, was longing. I could see the pentimento of the child still in him.

Johnny spoke softly in a voice just past the threshold of manhood. His smile, mistaken for charm, was longing. I could see the pentimento of the child still in him.