by Dwight Furrow

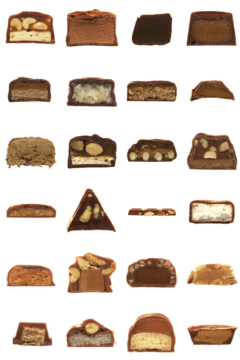

The term “gastronomy” has no agreed-upon, definitive meaning. Its common meaning, captured in dictionary definitions, is that gastronomy is the art and science of good eating. But the term is often expanded to include food history, nutrition, and the ecological, political, and social ramifications of food production and consumption. For my purposes, I want to focus on the conventional meaning of gastronomy for which that dictionary definition will suffice.

The term “gastronomy” has no agreed-upon, definitive meaning. Its common meaning, captured in dictionary definitions, is that gastronomy is the art and science of good eating. But the term is often expanded to include food history, nutrition, and the ecological, political, and social ramifications of food production and consumption. For my purposes, I want to focus on the conventional meaning of gastronomy for which that dictionary definition will suffice.

We have thousands of recipes from all over the world and, thanks to food historians, this data spans many generations. From this vast database, we know the combinations of ingredients that cooks have used to satisfy our need for enjoyment. We have practical guides to the techniques and methods that make each dish successful as elaborated in countless media devoted to cooking. And we have a robust science of cooking that explains the chemical interactions that occur when dishes are properly made and that also expands our understanding of what is possible. But we don’t have a general theory of the organization and structure of dishes that explains what it means for something to “taste good.” In other words, we can give accounts of what it means for a paella to taste good according to conventional standards of paella making, while acknowledging widespread disagreement on some of the details. But we have no theory of how that is related to a butter chicken or ossobuco tasting good. In gastronomy there is nothing akin to music theory or theories in the visual arts that elaborate the general conditions for the composition of recipes and no account of what kind of aesthetic achievement a dish or a meal is.

This is not to say there are no rules of thumb that guide chefs and cooks. Good dishes must be skillfully made, balanced, have enough flavor variation and texture to be interesting, be appropriate to the season or occasion, and be made from quality ingredients. But these factors make only a minimal contribution to a conceptual system that would organize the vast and highly differentiated world of cuisine. Read more »

One of the most interesting debates within the larger discussion around large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 is whether they are just mindless generators of plausible text derived from their training – sometimes termed “

One of the most interesting debates within the larger discussion around large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 is whether they are just mindless generators of plausible text derived from their training – sometimes termed “

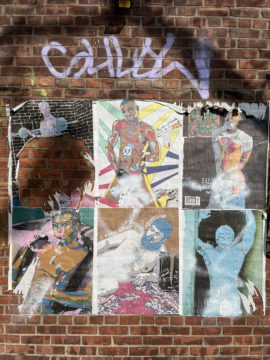

Misha Japanwala. Breastplate, ca. 2018.

Misha Japanwala. Breastplate, ca. 2018.

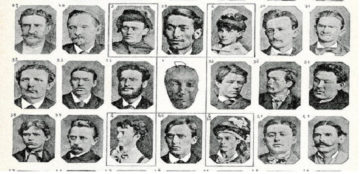

When they arrived in the U.S., Southern Italians brought with them the sense that they’d been branded as underdogs, that they belonged and would forever belong to a lower class, but the birth of the Italian-American gangster was rooted in attitudes toward the Mezzogiorno that dated back far earlier. After Italy was unified under Vittorio Emanuele II in 1861, a new national government imposed Piedmont’s centralized administrative system on the South, which led to violent rebellion against State authority. Politicians and intellectuals took pains to deflect responsibility for what they saw as the “barbarism” of the Mezzogiorno, and were particularly receptive to theories that placed the blame for the South’s many problems on Southern Italians’ own inborn brutishness. The decades following Unification saw the nascent fields of criminal anthropology and psychiatry establish themselves in the universities of Northern Italy; implementing the pseudosciences of phrenology and anthropometry in their search for evolutionary remnants of an arrested stage of human development manifested in the people of the Mezzogiorno, they used various instruments to measure human skulls, ears, foreheads, jaws, arms, and other body parts, catalogued these, and correlated them with undesirable behavioral characteristics, inventing in the process a Southern Italian race entirely separate from and unrelated to a superior Northern race and officially confirming the biological origins of Southern “savagery.”

When they arrived in the U.S., Southern Italians brought with them the sense that they’d been branded as underdogs, that they belonged and would forever belong to a lower class, but the birth of the Italian-American gangster was rooted in attitudes toward the Mezzogiorno that dated back far earlier. After Italy was unified under Vittorio Emanuele II in 1861, a new national government imposed Piedmont’s centralized administrative system on the South, which led to violent rebellion against State authority. Politicians and intellectuals took pains to deflect responsibility for what they saw as the “barbarism” of the Mezzogiorno, and were particularly receptive to theories that placed the blame for the South’s many problems on Southern Italians’ own inborn brutishness. The decades following Unification saw the nascent fields of criminal anthropology and psychiatry establish themselves in the universities of Northern Italy; implementing the pseudosciences of phrenology and anthropometry in their search for evolutionary remnants of an arrested stage of human development manifested in the people of the Mezzogiorno, they used various instruments to measure human skulls, ears, foreheads, jaws, arms, and other body parts, catalogued these, and correlated them with undesirable behavioral characteristics, inventing in the process a Southern Italian race entirely separate from and unrelated to a superior Northern race and officially confirming the biological origins of Southern “savagery.”