by Mike Bendzela

[Part One of this essay can be found here.]

Alexia, Redux

Throughout the winter of 2017, as he recovered from the stroke, Don went through a battery of therapies, including walking on a treadmill with and without handrails; navigating the winding corridors of the rehab center and having to find his way back to where he started; taking apart and putting back together block puzzles; scanning a large computer screen for numbered sequences.

I was invited to accompany him to his reading therapy sessions because his gay therapist got such a kick out of us. He would spend the first few minutes asking us about life on the farm. He wanted to know about milking cows and slopping pigs, shoveling shit, wringing the necks of unwanted roosters. Two husbands husbanding, har, har. He even devised a few bucolic reading exercises for Don.

Once the reading therapy began, it was painful to watch. Don would stare at the page upon which the therapist had printed a sentence in block letters:

IT WAS ON THE PIG.

The forefinger of Don’s left hand worked furiously as he struggled to recognize the words, like how I used to count on my fingers in math class. He had discovered he could bypass the damaged areas of his brain by transferring the task of letter recognition to his finger. Air writing, as it were. He eventually got around to naming letters without using his finger as a crutch.

“So, what was on the pig?” Don asked.

“I just made that up myself,” the therapist said.

One of the uncanniest exercises the therapist demonstrated for us: Three sets of three letters–two sets nonsensical, one an English word–were presented to Don in turn. Don simply had to identify which one was an actual word, not what it said.

WRO

EGG

XQD

“The middle one looks like a word.”

YRL

FDI

COW

“Bottom.”

We took the exercises home with us. I made flashcards and wrote function words in large letters: AS ON IF.

After weeks of this, and more therapy sessions—and feet of snowfall—he was reading full paragraphs provided by the therapist at home, albeit haltingly. There were such long pauses I was able to count the mechanical tick-tocks of the windup clock on the shelf in the kitchen.

“In an old . . . house . . . lived . . . an old . . . woman . . . named . . . Mrs. . . . Strange?”

“Strong,” I corrected, as the therapist had recommended.

“Oh. Mrs. Strong. . . . She . . . lived . . . up to her . . . name. . . .”

His alexia wasn’t helped by the fact that half his field of vision was gone. But he learned to anticipate full words and common phrases by scanning just the first few letters: WOM was usually “woman,” HOU “house.” But he had his bad days and second-guessed himself terribly. We eventually got through the story together and even laughed:

One day her doorbell rang. A man selling vacuum cleaners stood on her front porch. “Madam,” he said, “I want to show you something that you’ll never forget.”

“I do not want to see it,” said Mrs. Strong. “My house is full now and there is no room for anything else.”

But then the salesman threw a fistful of dirt on the floor. “Now, Mrs. Strong,” he said, “I want to make a bargain with you. If this vacuum cleaner does not pick up every bit of dirt, I’ll eat it.”

“Here’s a spoon,” said Mrs. Strong. “I don’t have electricity.”

He had to take a break as he had had a bad morning; he had woken up with very low blood sugar. He ate breakfast—French toast, bacon, apple slices—then took his injections, and his blood sugar shot sky high: rebound. He tried knocking it down with a few more units of short-acting insulin. He re-tested: even higher. It was like shooting skeet.

During his break, I tell him to re-test. I stand behind his chair while he gets out his finger-sticker.

“You’re hovering!”

“OK!” I sit down.

His blood sugar is 400.

“No wonder you couldn’t see to read!”

He dials up the insulin, takes his injection.

“Do you want to try reading later?”

“Put it in a pickle jar.”

(Meaning his brain.)

Seizure

His sleeping without hearing aids has led to some interesting exchanges. Once, he was snoring so loudly I had to reach over and push on his chin to open his airway.

He startled awake: “What?”

“Your snoring is terrible.”

He paused: I could sense him groping toward interpretation. “Did you hear that on the radio?”

Now it was my turn: “What?”

“You said, It’s snowing in Caribou?”

Later that night, as chunks of ice slid off the metal roof, Don grunted in his sleep, pained and desperate. It was a tone I knew like the winter chill. I shook him awake.

“Are you low?”

“Probably!”

I got up and went into the kitchen to get a cookie and a glass of juice, homemade grape juice canned in quarts, Don’s own recipe, which we keep on hand for just such occasions. I glanced at the shelf clock: It was 1:50 am.

He managed to sit up in bed and slurp the juice like hot tea. When I gave him the cookie, he chomped on it like a silly child.

I stuffed down my panic, went off to refill the glass, grabbed his glucose meter. From the kitchen I could hear him banging his head against the headboard. So, I grabbed the emergency glucagon kit as well. More banging, then sobbing. I ran back in and tried to get him to sit up on the siderail of the bed, but he jerked the blankets away and turned over violently.

“No! It’s cold!”

I got him to sit up against his pillows. He took the glass from me, tipped his head back and began pouring juice right into his open mouth.

I got the glucose meter set up on the bedside table and grabbed his hand to try to get a blood sample; he would not open his fist; his tough fingernails dug into my hand. I pried a finger loose and managed to click the finger-sticker and squeeze a drop of blood out onto the test strip: five seconds later, the machine beeped: 48.*

I tried to sit him up again, but he fought it. Then he fell back onto the bed, limp. I shook him hard and yelled his name, but he was unconscious. I felt for a carotid pulse: strong and regular. As I struggled to get his sweatpants off his hip, he roused and began fighting me again. Somehow—there is no actual memory here—I opened the glucagon emergency kit, got the cap off the bottle of powder, shot the liquid contents of the pre-filled syringe into the bottle, swirled the contents until the powder dissolved, reinserted the syringe into the bottle, and drew up the shot. Now he was rocking and sobbing in bed. I shot the glucagon into his left hip near the buttock, then picked up the phone. . . .

By the time red lights flickered past the kitchen window, Don was sitting at the table, polishing off a cookie. His blood sugar had come up to 67.

Two EMTs and a firefighter piled into the kitchen with their giant bags, tracking in snow. One EMT knelt beside Don and dug around in his kit for a stethoscope and blood pressure cuff.

“What’s going on tonight, young man?” the on-duty paramedic said to Don. I knew him from my days as a volunteer EMT; a big, gentle guy; calm as a puddle. He had been to the farm before, a week after the stroke, when Don had become very confused during supper, and I had pressed the panic button. They had transported him to Portland, but it turned out to be a false alarm. Just part of the initial stroke’s “evolution.”

“I’m becoming a frequent flyer,” Don said.

“That’s all right. We love coming here, don’t we guys?” The others nodded.

I, too, had stood in many such kitchens in the wee hours, telling jokes, the emergency having passed. It was unsettling being on the other end, but I knew it was bound to happen.

“You want to stick your finger for me?” The medic sat at the table and opened a laptop computer. “If you’re over 80 we can get out of here and let you go back to bed.”

I told the paramedic the story of Don’s seizure, the glucagon injection that revived him, while he typed away on the computer.

The EMT called out vital signs: “BP 154 over 100. Pulse strong, in the 60s.”

Don’s blood sugar had shot up to 150.

The medic nodded at one of the firefighters, who took his radio off his hip and stepped outside the door.

“You should eat something,” the medic said, “because you know it’s going to drop again.”

“I already took a cookie,” Don said.

We all got a kick out of that.

Tears

A dreary day in April. No surprise there. Good day to fill out Don’s advanced directive. “I don’t think I’m going to be around much longer,” he has told me.

I am filling Mason jars with bulk spices that have arrived by morning mail. The ground red pepper is clumped up inside the bag, and when I tip it toward the wide-mouthed funnel all the pepper comes out at once. The air in the kitchen becomes so toxic my throat and sinuses catch fire. We both begin choking. “Jesus Christ!”

We begin filling out the paperwork. It is not difficult as I’m the agent. I simply transcribe his wishes, in his own words. I ask him how he wants to be treated if he ever falls into a coma.

“I just don’t want to be a burden to you.”

“I’m not writing that down.”

He sits at the table and puts his hands over his face. I think it is the red pepper; then he begins sobbing.

My sinuses are stopped up solid, and my eyeballs begin shedding burning tears. I catch my breath and choke out, “But you’re not a burden, you’re my husband!” Mucus streams out of my nose and eyes. I get out my handkerchief and blow and blow. I cannot seem to get the pepper out. “You’re no burden, you’re just a pain in the ass!”

“You know there’s a difference!” he sobs, his face a dripping mess.

Headache, Redux

I walk into the kitchen upon arriving home from classes. Don is standing there at the iron sink, surrounded by the pine panel cabinetry and handsome open shelves he has designed and built himself.

“I think some of my students have had strokes.” I say. I toss my bag onto the seat of a chair. “They can read, but they can’t write.”

Don is quiet. I can tell he is not feeling well.

“What is it?”

“I had headache today,” he says.

Six months ago, a headache had been the first sign of his stroke. He has been complaining about his vision lately as well. It is typically April, “black as a pocket,” he puts it, and the low light exacerbates his diminished eyesight. He says it is like “looking through a screen.”

I have to say it: “Do you think you’re having another stroke?” I speak too loudly.

At that moment, our landlady and longtime friend, Claudia, knocks and comes in, carrying a foil-wrapped chunk of salmon crusted with pistachios, about the most scrumptious thing I have ever put in my mouth. She and her husband Ken come up from Washington D. C. every summer to farm with us. Don spent over thirty years restoring the old farmhouse for her father, and when he died she and Ken took over ownership. Maine summers are good for Ken; he has a constitution such that he is prostrate in temperatures over 80 degrees. Don and I are now permanent caretakers of the family homestead.

I absently take the foil package from her, as if it were a piece of litter she has given me to throw in the trash.

Seeing how upset I am, Don says, “You wonder why I don’t want to tell you anything?”

“He has a point there,” Claudia says.

We are in that weird zone: we have to decide whether or not to call the ambulance—again—or wait and see. Some strokes are reversible and need immediate care. The Golden Hour, we called it in rescue. But these two clowns are more focused on my being upset.

My response is to fling the package of salmon across the room.

“I said I had a headache,” Don says. “It’s gone away.”

“How long did you have it?”

“About an hour.”

“Are you still having problems with your vision?”

“I don’t want to go to the hospital. There’s nothing they can do. You go in with a stroke and they say, ‘Well, that’s interesting, but there’s nothing we can do.’”

So that settles it. I apologize to Claudia for chucking her gift.

That afternoon, the four of us go out and cut down trees along the edge of the field. For three hours, we haul brush to the burn pile until we are wiped out.

Whirlwind

June at last.

This afternoon, I must cover seeded rows of corn with cloth. Half of a field is fallow, the other half planted to potatoes and three varieties of sweet corn for our CSA customers. If I don’t lay down cloth, crows will find the corn sprouts and pull them out. I learned this the hard way.

We have saved old row covers—torn, dirty, synthetic fabric—from previous years for this occasion. I get out the cloth and lay it over the newly planted corn rows and weigh it down with stones and piles of dirt. On flat ground the cloth will stay put until the corn sprouts push the cloth off the earth. When the stalks are tall enough that crows won’t bother them, we can take the fabric off and let the corn straighten up.

As I work, the initial crisis on that morning in October 2016 streams back to me like a remembered dream.

Don had been complaining of a persistent, low-grade headache and decided he needed to see our doctor about it. With Type 1 diabetes, you don’t mess around.

He was upstairs changing out of his work clothes, getting ready for his appointment, I was downstairs loading firewood, when he yelled out, “My vision just split in half and the two halves don’t line up.”

All at once, I was running up the stairs, saying, “What did you say?” and dialing 9-1-1 on my cellphone.

While I’m kicking dirt over cloth and finding stones to weigh it down, Don comes out of the barn to help.

“Can’t see shit,” he says, “but at least I can still do stuff.”

He begins gathering bricks from an old brick pile to weigh down the cloth properly. I help him gather armloads of bricks and plop them on the cloth. He makes sure the corners are pulled taut, that the sections of fabric are lapped enough to seal out the crows, that the bricks are regularly spaced and evenly distributed. It takes a lot of time but that’s the way he is now.

Nine two-hundred-foot rows—about six thousand square feet—lie completely covered in white fabric. Those crows are going to be pissed. I imagine it from their lofty perspective: A big patch of gauze placed over raw earth.

Don returns to the barn.

The other half of the plot is scatter-seeded with a cover crop of oats. I climb aboard the tractor and begin lightly disking in the seed so foraging wild turkeys won’t get it all. As I drive across the seed bed, I turn in my seat to watch the disk harrow. Something over at the corn patch catches my eye:

One big length of cloth is up on end, shimmying. It twists and flaps in one wild motion.

Another length gets up off the ground and joins it, wrapping itself around the midsection of the shimmying cloth, the two of them now cycling around together in an eccentric orbit several feet above the dirt, their rotation intensifying as the dust devil wends its way right up the middle of my corn plot.

Now wound up together, the cloth bundle lifts off.

I shut off the tractor and watch.

The spinning ball of sheets lands in the crown of the largest maple tree on the property, a tree so tall we thought about cutting it down because it shades a half-acre of ground. The cloths are hung up there good and will stay there, like a gigantic mass of dirty laundry, for years to come.

Overhead, I see another fifty-foot section of fabric undulating high in the blue sky. “Jesus,” I say, to no one in particular. It drifts over an adjacent three-acre field, hangs there, maybe two hundred feet up, for what seems a full minute, then floats downward, taking its time, like a leaf sinking in water.

The whirlwind has dissipated. I wish Don had stuck around to see it.

Our landlady, Claudia, is striding across the field underneath the falling fabric, looking up at it in her funky, straw sun bonnet. Her whole head looks like a laundry basket.

All that is left on the bare ground in the corn plot are lines of bricks.

I dismount the tractor and gather up some remaining cloth bunched off to the side—I find it is torn completely in half, right up the middle.

An hour of work, two man-hours, gone. But worse things have happened: this is just a corn patch. This kind of thing happens to whole lives, even. Nature suddenly up and says, “Who do you think you are?”

That floating fabric finally lands in the field a hundred yards away. Claudia stoops down and gathers it up. I will have to retrieve it and spread it over the ground again or those crows will do their dirty work.

When I bend over and begin picking up bricks off the dirt, I find scraps of torn cloth still lying underneath them.

*This hypoglycemic incident occurred in 2017, back before Don got a continuous glucose monitor, once he qualified for Medicare. The old stick-and-pick-the-finger method seems so primitive now.

__________________

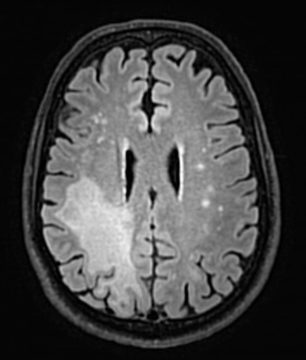

Image

“MRI of patient with PML” by National Institutes of Health (NIH) is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0.