by John Allen Paulos

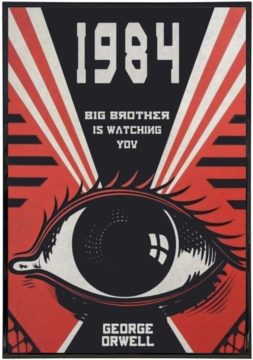

Kurt Gödel was a logician whose work in mathematical logic was seminal and fundamental. His famous incompleteness theorems, in particular, have changed our view of mathematics and computer science. He was born in Austria and lived through political turmoil there before fleeing the country after the Nazis annexed it in 1938. He came to America and settled for a time at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where after the war in 1947 he applied for US citizenship. While preparing for the test, the ever punctilious Gödel noted a logical inconsistency in the Constitution, a loophole that would allow American democracy to legally become a dictatorship. His friends at the Institute, including Einstein, counseled him not to express his misgivings when he appeared before the judge lest he not be granted citizenship. He did, but happily the judge ignored them.

It’s never been clear what Gödel’s logical objection was, but it’s likely, as F. E. Guerra-Pujol speculated in his 2012 paper, “Gödel’s Loophole,” that it centered around Article V of the U.S. Constitution, which described the procedure by which the Constitution might be amended. Given that Gödel’s proof of his first incompleteness theorem involves a sort of self-reference, it’s not surprising that his loophole arises from the observation that Article V’s procedures to amend the Constitution might be employed to amend itself. Article V could be modified to make it easier to amend Article V. Thus, although Article V makes the Constitution difficult to amend, an amended Article V could make it easier to do so. There could also be amendments to the amendments to make it easier still, allowing future politicians to do away with the constitutional safeguards of fundamental rights in the Constitution. Read more »

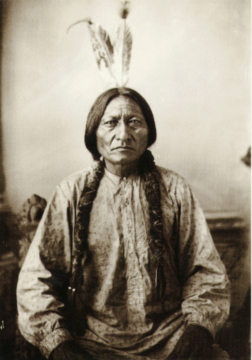

Jeffrey Gibson. Chief Black Coyote, 2021.

Jeffrey Gibson. Chief Black Coyote, 2021.

Lucky you, reading this on a screen, in a warm and well-lit room, somewhere in the unparalleled comfort of the twenty-first century. But imagine instead that it’s 800 C.E., and you’re a monk at one of the great pre-modern monasteries — Clonard Abbey in Ireland, perhaps. There’s a silver lining: unlike most people, you can read. On the other hand, you’re looking at another long day in a bitterly cold scriptorium. Your cassock is a city of fleas. You’re reading this on parchment, which stinks because it’s a piece of crudely scraped animal skin, by the light of a candle, which stinks because it’s a fountain of burnt animal fat particles. And your morning mug of joe won’t appear at your elbow for a thousand years.

Lucky you, reading this on a screen, in a warm and well-lit room, somewhere in the unparalleled comfort of the twenty-first century. But imagine instead that it’s 800 C.E., and you’re a monk at one of the great pre-modern monasteries — Clonard Abbey in Ireland, perhaps. There’s a silver lining: unlike most people, you can read. On the other hand, you’re looking at another long day in a bitterly cold scriptorium. Your cassock is a city of fleas. You’re reading this on parchment, which stinks because it’s a piece of crudely scraped animal skin, by the light of a candle, which stinks because it’s a fountain of burnt animal fat particles. And your morning mug of joe won’t appear at your elbow for a thousand years.

Harry Frankfurt died on July 16, 2023. As a philosophy student I came to appreciate him for his work on freedom and responsibility, but as a high school word nerd, I came to know him the way other shoppers did: as the author of one of those small books near the bookstore checkout line. That book, On Bullshit, had exactly the right title for impulse-buying, which has to explain how Frankfurt became a bestselling author in a field not known for bestsellers.

Harry Frankfurt died on July 16, 2023. As a philosophy student I came to appreciate him for his work on freedom and responsibility, but as a high school word nerd, I came to know him the way other shoppers did: as the author of one of those small books near the bookstore checkout line. That book, On Bullshit, had exactly the right title for impulse-buying, which has to explain how Frankfurt became a bestselling author in a field not known for bestsellers.

I had my first experience with Daylight Saving Time when I was 9 or 10 years old and living in Phoenix. Most of the country was on DST, but Arizona wasn’t. I knew DST as a mysterious thing that people in other places did with their clocks that made the times for television shows in Phoenix suddenly jump by one hour twice a year. In a way, that wasn’t a bad introduction to the concept. During DST, your body continues to follow its own time, as we in Phoenix followed ours. Your body follows solar time, and it can’t easily follow the clock when it suddenly jumps forward.

I had my first experience with Daylight Saving Time when I was 9 or 10 years old and living in Phoenix. Most of the country was on DST, but Arizona wasn’t. I knew DST as a mysterious thing that people in other places did with their clocks that made the times for television shows in Phoenix suddenly jump by one hour twice a year. In a way, that wasn’t a bad introduction to the concept. During DST, your body continues to follow its own time, as we in Phoenix followed ours. Your body follows solar time, and it can’t easily follow the clock when it suddenly jumps forward.

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

Barbara Chase-Riboud. Untitled (Le Lit), 1966.

Barbara Chase-Riboud. Untitled (Le Lit), 1966.