by O. Del Fabbro

I met Kseniia during my second visit to Ukraine, in June 2023. The moment I met her, I knew that this thirty-four-year-old woman is a special one. Kseniia belongs to the type of women who made Molotov cocktails to help defend Kyiv in March 2022. “I had some romantic idea to create these Molotov cocktails, because I heard that it might come to urban warfare, and I wanted to help. We spent a whole day making them, but the smell of petrol was awful.” Nevertheless, Kseniia made several boxes.

I met Kseniia during my second visit to Ukraine, in June 2023. The moment I met her, I knew that this thirty-four-year-old woman is a special one. Kseniia belongs to the type of women who made Molotov cocktails to help defend Kyiv in March 2022. “I had some romantic idea to create these Molotov cocktails, because I heard that it might come to urban warfare, and I wanted to help. We spent a whole day making them, but the smell of petrol was awful.” Nevertheless, Kseniia made several boxes.

The concept of women making Molotov cocktails was something I only knew from news reports, and I distinctly remember the impression that such women made on my perception of the willingness of Ukrainians to not only resist but also fight the aggressor. To suddenly be sitting in front of such a woman seemed surreal to me.

The more I listened to Kseniia’s numerous stories, the more it occurred to me that she was much more than just a simple activist. Kensiia is a hub of different intense experiences: sadness, happiness, danger, beauty. Kseniia, I believe, has seen it all; and her stories speak for themselves.

The Saddest Experience

Kseniia opened and still runs two aid organizations. One supplies the military and civilians with food, clothes, drones, night vision goggles, whatever people contact her for. The other organization repairs roofs of destroyed houses, especially in the countryside, and supplies the military with used cars. So far, the later organization called ‘livyj bereh’ – which means the left bank of the river – has repaired two hundred roofs and donated more than forty cars to the military. In total, she raised more than half a million euros. “Pink Floyd sent us some money too,” says Kseniia with a little pride. The controversy around the provocative statements on the war of the former Pink Floyd member, Roger Waters, is something Kseniia has no clue about and also does not care. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait at Itaimbezinho Canyon, Brazil, March 2014.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait at Itaimbezinho Canyon, Brazil, March 2014.

I picture the LORD God as a child psychologist—very much of a type, vaguely professorial, plucked from the ’50s. Picture him with me: shorn and horn-rimmed, his fingernails immaculate, he’s on his way to a morning appointment. As he kneels in the garden to tie his shoe, his starched white shirtfront strains against his gut.

I picture the LORD God as a child psychologist—very much of a type, vaguely professorial, plucked from the ’50s. Picture him with me: shorn and horn-rimmed, his fingernails immaculate, he’s on his way to a morning appointment. As he kneels in the garden to tie his shoe, his starched white shirtfront strains against his gut.

The first

The first

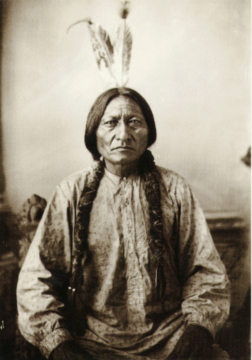

Jeffrey Gibson. Chief Black Coyote, 2021.

Jeffrey Gibson. Chief Black Coyote, 2021.

Lucky you, reading this on a screen, in a warm and well-lit room, somewhere in the unparalleled comfort of the twenty-first century. But imagine instead that it’s 800 C.E., and you’re a monk at one of the great pre-modern monasteries — Clonard Abbey in Ireland, perhaps. There’s a silver lining: unlike most people, you can read. On the other hand, you’re looking at another long day in a bitterly cold scriptorium. Your cassock is a city of fleas. You’re reading this on parchment, which stinks because it’s a piece of crudely scraped animal skin, by the light of a candle, which stinks because it’s a fountain of burnt animal fat particles. And your morning mug of joe won’t appear at your elbow for a thousand years.

Lucky you, reading this on a screen, in a warm and well-lit room, somewhere in the unparalleled comfort of the twenty-first century. But imagine instead that it’s 800 C.E., and you’re a monk at one of the great pre-modern monasteries — Clonard Abbey in Ireland, perhaps. There’s a silver lining: unlike most people, you can read. On the other hand, you’re looking at another long day in a bitterly cold scriptorium. Your cassock is a city of fleas. You’re reading this on parchment, which stinks because it’s a piece of crudely scraped animal skin, by the light of a candle, which stinks because it’s a fountain of burnt animal fat particles. And your morning mug of joe won’t appear at your elbow for a thousand years.

Harry Frankfurt died on July 16, 2023. As a philosophy student I came to appreciate him for his work on freedom and responsibility, but as a high school word nerd, I came to know him the way other shoppers did: as the author of one of those small books near the bookstore checkout line. That book, On Bullshit, had exactly the right title for impulse-buying, which has to explain how Frankfurt became a bestselling author in a field not known for bestsellers.

Harry Frankfurt died on July 16, 2023. As a philosophy student I came to appreciate him for his work on freedom and responsibility, but as a high school word nerd, I came to know him the way other shoppers did: as the author of one of those small books near the bookstore checkout line. That book, On Bullshit, had exactly the right title for impulse-buying, which has to explain how Frankfurt became a bestselling author in a field not known for bestsellers.