by Martin Butler

What do people want? Not such a simple question as it seems. Tom Turcich, the guy who recently walked around the world passing through 38 countries over seven years, claimed that from what he had experienced people just want to make a little money and hang out with their families, which sounds like a fairly hopeful conclusion, though we mustn’t forget that this was clearly not enough for Tom himself. If true, this simple answer leads on to other important questions. If most people have such modest wants, why would they care about the big political and ethical questions that philosophers agonise about? Might it be the case that equality, human rights, democratic representation and so on are pretty much beside the point for the majority? Why would those with a good enough life need to bother with such wider issues? We need to remember here that, historically, political ideals took off as real issues only when they entered people’s everyday lives rather than as abstract ideals debated by the intellectual few. The important struggles of the past – and present – have been prompted when people, or at least significant groups of them, were unable to enjoy an adequately resourced and secure life with their families which was not dependent on the whim of those in positions of power. So there certainly is a very clear connection between the modest wants that Tom Turcich identifies and the big political questions. He draws the conclusion that while people are on the whole good, he can’t say the same for the systems they often live under.

With the advent of mass media and the internet in particular our whole landscape has changed dramatically. For most of history the vast majority of people lived essentially local lives with little or no knowledge of a wider world picture. Now we can know of the sufferings of people on the other side of the world as easily as we can the goings on in the next street or village, in fact often more easily. We can gain a sophisticated grasp of the latest scientific information on climate breakdown and the many other negative effects of humanity on the environment. The distinction between our own personal concerns and those issues which might be regarded as more remote and abstract becomes increasingly blurred. Read more »

Jesus Rafael de Soto. Penetrable, at Olana State Historical Site, New York.

Jesus Rafael de Soto. Penetrable, at Olana State Historical Site, New York.

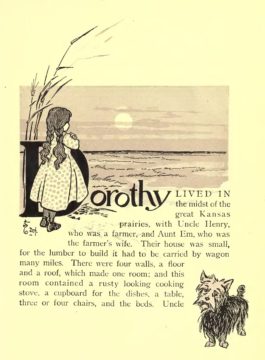

On a small paper bag maybe from a bookstore, one side Romeo’s soliloquy, “But soft! What light from yonder window breaks?” On the other side, these words: “Dorothy lived in the midst of the great Kansas prairies, with Uncle Henry, who was a farmer, and Aunt Em, who was the farmer’s wife. Their house was small, for the lumber to build it had to be carried by wagon many miles. There were four walls, a floor and a roof, which made one room; and this room contained a rusty looking cook stove, a cupboard for the dishes, a table, three of four chairs, and the beds. Uncle Henry and Aunt Em had a big bed in one corner, and Dorothy a little bed in another corner. There was no garret at all, and no cellar–except a small hole dug in the ground, called a cyclone cellar, where the family could go in case one of those great whirlwinds arose, mighty enough to crush any building in its path. It was reached by a trap-door in the middle of the floor, from which a ladder

On a small paper bag maybe from a bookstore, one side Romeo’s soliloquy, “But soft! What light from yonder window breaks?” On the other side, these words: “Dorothy lived in the midst of the great Kansas prairies, with Uncle Henry, who was a farmer, and Aunt Em, who was the farmer’s wife. Their house was small, for the lumber to build it had to be carried by wagon many miles. There were four walls, a floor and a roof, which made one room; and this room contained a rusty looking cook stove, a cupboard for the dishes, a table, three of four chairs, and the beds. Uncle Henry and Aunt Em had a big bed in one corner, and Dorothy a little bed in another corner. There was no garret at all, and no cellar–except a small hole dug in the ground, called a cyclone cellar, where the family could go in case one of those great whirlwinds arose, mighty enough to crush any building in its path. It was reached by a trap-door in the middle of the floor, from which a ladder I’ve recently started playing pickup basketball again. When I was younger, I played basketball all the time. At two or three years old, we had a toy hoop with a bright orange rim, white backboard, blue pole, and black base. It was, I believe, a “Little Tikes” brand hoop; I’ve just looked it up online, and my research seems to confirm this. In any case, I will now remember it this way—the vague memory I hold has solidified into one canonical version. But it might have been a different brand, the base of the hoop might have been a different color.

I’ve recently started playing pickup basketball again. When I was younger, I played basketball all the time. At two or three years old, we had a toy hoop with a bright orange rim, white backboard, blue pole, and black base. It was, I believe, a “Little Tikes” brand hoop; I’ve just looked it up online, and my research seems to confirm this. In any case, I will now remember it this way—the vague memory I hold has solidified into one canonical version. But it might have been a different brand, the base of the hoop might have been a different color.

I’ve been visiting Ontario this month. Which is a wildly non-specific thing to say, since the province of Ontario, though only the second largest of Canada’s constituent divisions, boasts a surface area greater than those of Germany and Ukraine combined. But while I would normally designate as my destination the city in Ontario in which I mean to stay during my annual visit to my home and native land—as for instance Toronto, the provincial capital, where I went to high school and university; or Kingston, once Canada’s Scottish-Gothic capital, where my brother has settled with his family—the particular reason for this year’s sojourn, which began with a brief visit to relatives in Montreal, was my niece’s wedding, on August 12, celebrated at her fiancé’s family home in Frankford, with guests put up in the towns surrounding that hamlet on the River Trent, in Hastings County, the second largest of Ontario’s 22 “upper-tier” administrative divisions. Which all feels to me quite uncannily foreign, not to say unutterably vague. Hence simply: I’ve been visiting Ontario this month.

I’ve been visiting Ontario this month. Which is a wildly non-specific thing to say, since the province of Ontario, though only the second largest of Canada’s constituent divisions, boasts a surface area greater than those of Germany and Ukraine combined. But while I would normally designate as my destination the city in Ontario in which I mean to stay during my annual visit to my home and native land—as for instance Toronto, the provincial capital, where I went to high school and university; or Kingston, once Canada’s Scottish-Gothic capital, where my brother has settled with his family—the particular reason for this year’s sojourn, which began with a brief visit to relatives in Montreal, was my niece’s wedding, on August 12, celebrated at her fiancé’s family home in Frankford, with guests put up in the towns surrounding that hamlet on the River Trent, in Hastings County, the second largest of Ontario’s 22 “upper-tier” administrative divisions. Which all feels to me quite uncannily foreign, not to say unutterably vague. Hence simply: I’ve been visiting Ontario this month. Sughra Raza. Untitled, July 2020.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, July 2020.