by Dwight Furrow

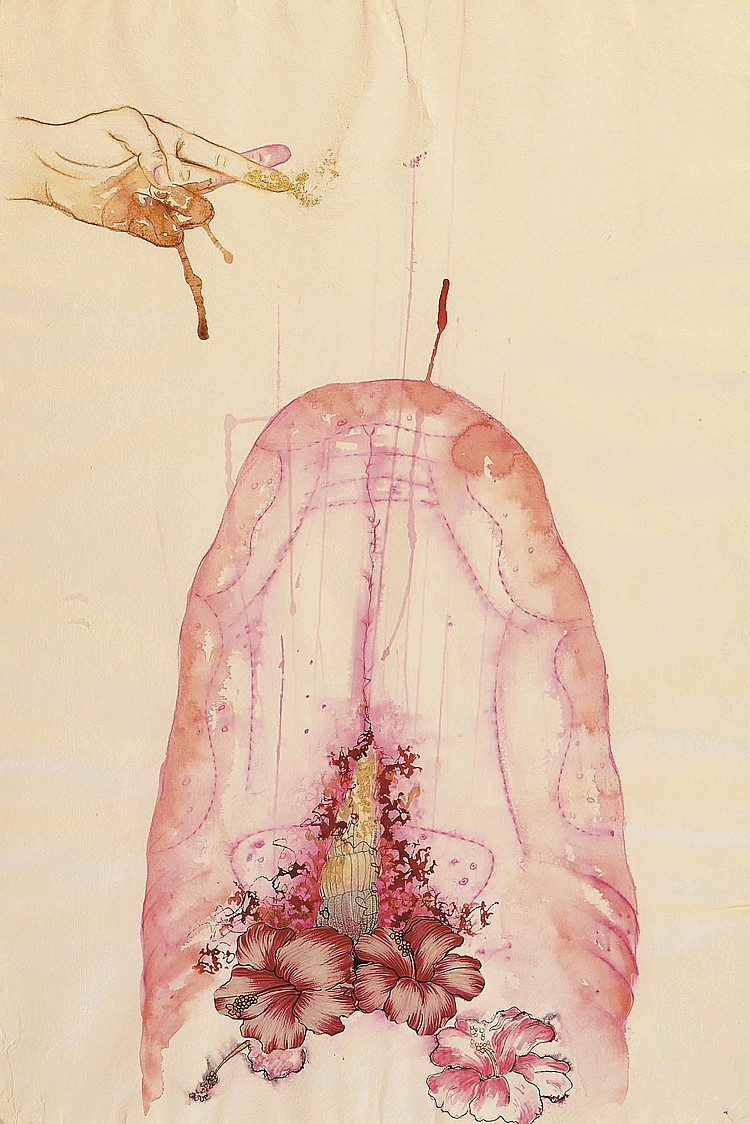

Aesthetic properties in art works are peculiar. They appear to be based on objective features of an object. Yet, we typically use the way a work of art makes us feel to identify the aesthetic properties that characterize it. However, dispassionate observer cases show that even when the feelings are absent, the aesthetic properties can still be recognized as such. Feelings seem both necessary yet unnecessary for appreciation of the work.

Aesthetic properties in art works are peculiar. They appear to be based on objective features of an object. Yet, we typically use the way a work of art makes us feel to identify the aesthetic properties that characterize it. However, dispassionate observer cases show that even when the feelings are absent, the aesthetic properties can still be recognized as such. Feelings seem both necessary yet unnecessary for appreciation of the work.

How do we square this circle?

When we ascribe to works of art properties such as beautiful, melancholy, mesmerizing, charming, ugly, awe-inspiring, magnificent, drab, or dynamic we are typically reporting how the work affects us, and we often use what we loosely call “feelings” to help in the ascription. A painting is charming if the viewer feels charmed. The architecture of a building is awe-inspiring if an admirer has the feeling of being awed. To say that a musical passage is beautiful but it leaves me uninspired and bored is peculiar and would require some special explanation for what is meant by “beautiful” in this case. We typically use the degree and kind of pleasure we feel about an object to be one measure of its beauty. The feelings involved in our response to artworks or other aesthetic objects need not be full blown emotions. As many commentators have pointed out, a sad song does not necessarily make one feel sad if you have nothing to be sad about. In fact, we often find sad songs exhilarating. Yet sad songs make us feel an analog to sadness which helps us attribute the property “sad” to the song.

In other words, there is something that it is like to feel charmed, awed, in the presence of beauty, or “sad-adjacent” that typically accompanies the identification of that property in an object. And the feeling state helps us identify the property. We know a film is amusing because it makes us feel amused, joyful because it sparks feelings of joy, etc.

But this raises a puzzle about dispassionate observers. Read more »

ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say

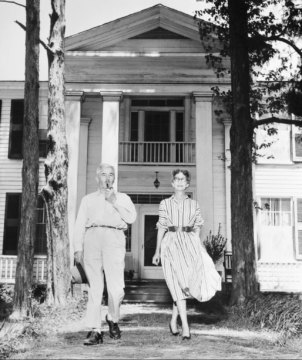

ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say  The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

Today marks eight years since I had my last drink. Or maybe yesterday marks that anniversary; I’m not sure. It was that kind of last drink. The kind of last drink that ends with the memory of concrete coming up to meet your head like a pillow, of red and blue lights reflected off the early morning pavement on the bridge near your house, the only sound cricket buzz in the dewy August hours before dawn. The kind of last drink that isn’t necessarily so different from the drink before it, but made only truly exemplary by the fact that there was never a drink after it (at least so far, God willing). My sobriety – as a choice, an identity, a life-raft – is something that those closest to me are aware of, and certainly any reader of my essays will note references to having quit drinking, especially if they’re similarly afflicted and are able to discern the liquor-soaked bread-crumbs that I sprinkle throughout my prose. But I’ve consciously avoided personalizing sobriety too much, out of fear of being a recovery writer, or of having to speak on behalf of a shockingly misunderstood group of people (there is cowardice in that position). Mostly, however, my relative silence is because we tribe of reformed dipsomaniacs are a superstitious lot, and if anything, that’s what keeps me from emphatically declaring my sobriety as such.

Today marks eight years since I had my last drink. Or maybe yesterday marks that anniversary; I’m not sure. It was that kind of last drink. The kind of last drink that ends with the memory of concrete coming up to meet your head like a pillow, of red and blue lights reflected off the early morning pavement on the bridge near your house, the only sound cricket buzz in the dewy August hours before dawn. The kind of last drink that isn’t necessarily so different from the drink before it, but made only truly exemplary by the fact that there was never a drink after it (at least so far, God willing). My sobriety – as a choice, an identity, a life-raft – is something that those closest to me are aware of, and certainly any reader of my essays will note references to having quit drinking, especially if they’re similarly afflicted and are able to discern the liquor-soaked bread-crumbs that I sprinkle throughout my prose. But I’ve consciously avoided personalizing sobriety too much, out of fear of being a recovery writer, or of having to speak on behalf of a shockingly misunderstood group of people (there is cowardice in that position). Mostly, however, my relative silence is because we tribe of reformed dipsomaniacs are a superstitious lot, and if anything, that’s what keeps me from emphatically declaring my sobriety as such.