by Mike Bendzela

The funeral director is a good guy, both sedate and friendly. I wait for him to wrap up his service in advancing rain before driving up to the site to close the grave. The mourners depart the gravesite but do not leave the cemetery. They hang out near their pickup trucks, some talking animatedly.

“Wait around awhile and you might be able to collect some returnables,” the director says. I look over: the mourners have already cracked open beers and canned “cocktails.”

Then I look at the urn, a small squat box made of “cultured marble,” perched on a pedestal over the pit I have dug and covered with plywood and hemlock boughs. “Forty is way too young,” I say. Before coming over, I searched the obituary online. Theoretically, I could have a son that age.

“Fentanyl, I’m pretty sure,” the director says, his tone lowered. “It’s worse than covid now.”

In 2021 and 2022, there were at least three covid victims interred in our cemetery; I know because I had to make out receipts for the families to receive government reimbursements for funeral expenses. I don’t know how many opioid deaths there have been.

“We have at least one of these going at any time now,” he says, meaning funerals for overdose deaths. “It’s that bad.”

As the rain picks up, the mourners scoot into their trucks with their beverages and drive off. No returnable deposits for me on this Day of Our Lord.

I put the urn into its hole in the same plot as the deceased man’s infant daughter. Yes, this place is a veritable garden of sorrow.

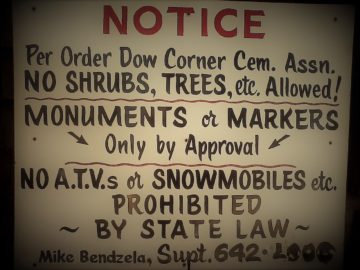

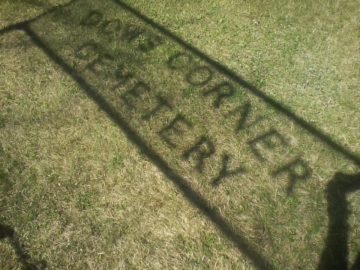

There is nothing spooky, mystical, or Gothic about this cemetery. It is simply five acres of weedy grass and stone monuments, clumps of (largely plastic) flowers and flapping American flags. In addition to those interred over the centuries, this place is occupied by turkeys, mockingbirds, and deer. The deer eat everything they desire, especially the leaves of hosta plantings around gravestones. The turkeys claw up the dead grass caused by the four previous years of spring drought and turn it into a playpen where they take dust baths. Only the mockingbirds do no damage, but their manifold vocalizations can sound insanely out of place here.

After topping the grave with a pathetic square of drought-damaged sod, I haul off the excess gravel, sand, and rocks in my pickup and toss it all over an embankment at the back of the cemetery, just before a downpour commences. Little by little, we replace the deposits under the sod with vaults, urns, concrete footings, and stone markers. But this place will never run out of rocks nor stories that can make you cry. Or laugh. In addition to the sorrow and sadness and shock, this place is stocked with absurdity, irony, satire.

*

It is the end of July, yet I have only interred three people, which is very unusual–we average about fifteen funerals per season (May-Nov). Year by year the number of full burials decreases, and the number of cremation burials increases, so that in the four years I have been superintendent here the ratio of full burials to cremation burials has dropped to one-in-three. Having seen what goes into interring caskets (backhoe, concrete vault, crane, etc.), full interment of my own remains will happen over my dead body. A cannister dropped in a hole is fine with me, or my winding-sheet-wrapped corpse rolled into a pit. But many folks still require full, royal treatment, and their survivors still heap their graves with the usual slabs and ornaments and doodads: cans of beer, opened and unopened; cigarettes, whole and butt ends; odd rocks and polished stones; stuffed animals, even a small pot metal dog figurine that chipped my mower blade. Three thousand years hence, if Earth has not been fried to a cinder, archaeologists who stumble upon burial sites such as this will wonder, “Who the hell did these people think they were?”

It is the end of July, yet I have only interred three people, which is very unusual–we average about fifteen funerals per season (May-Nov). Year by year the number of full burials decreases, and the number of cremation burials increases, so that in the four years I have been superintendent here the ratio of full burials to cremation burials has dropped to one-in-three. Having seen what goes into interring caskets (backhoe, concrete vault, crane, etc.), full interment of my own remains will happen over my dead body. A cannister dropped in a hole is fine with me, or my winding-sheet-wrapped corpse rolled into a pit. But many folks still require full, royal treatment, and their survivors still heap their graves with the usual slabs and ornaments and doodads: cans of beer, opened and unopened; cigarettes, whole and butt ends; odd rocks and polished stones; stuffed animals, even a small pot metal dog figurine that chipped my mower blade. Three thousand years hence, if Earth has not been fried to a cinder, archaeologists who stumble upon burial sites such as this will wonder, “Who the hell did these people think they were?”

The cemetery sits just a few hundred feet down the road from the old Maine farmhouse where my spouse and I are tenants, so, I can ride my lawnmower to work. It was once all a contiguous piece of land, hayfield and orchard, and over the years historical owners of the property have deeded real estate to the cemetery for expansion. A full mowing and trimming job at the place now takes about 16 hours. It takes me several days as I cannot stand to sit on the mower for more than a couple of hours at a time. Visitors tell me the grounds look nice, that I seem to be doing a good job.

“I’ve heard no complaints,” I respond.

Cemetery work, like hair salons and sex, attracts jokes and bad puns like fleas and lice: When I started the job, which overlapped with a small farming gig, I joked that I would paint a fictional business name on the side of my pickup truck, Planten & Planten. I imagined that if someone were to ask me how much I got paid, I would respond, “Well, I don’t make a killing. . . . But I don’t exactly make a living, either.” I’m such a funny guy, couldn’t you just die?

In addition to mowing and trimming, I dig. Full burials are hired out, but I can hand-dig the holes for urns. My rule of thumb for the digging depth of cremation burials is as follows: Thirty inches or until the first big rock. I have discovered over the years that the tops of some old burial vaults lie only six inches below the surface for the same reason: BFR got in the way. Sometimes it doesn’t take much digging to disinter a chunk of granite “from away,” as the Maine expression goes.

Not for nothing the sides of the roads here in Maine are lined with stone walls. Using just oxen and “stone boats,” 18th-century European interlopers on the land began by clearing the fields as best they could and demarcating their properties with handsome boulder fences. They did not–and could not–get all the rocks out. As this particular area of the state does not yield well to the plow (or spade), “They grew cows and apples here,” as my spouse likes to say.

At the university where I teach (my main job), I sometimes have to walk past the Department of Geography to get to a class. I am always fascinated by the maps on the walls in the hallway. During one such trip I discovered a large soils map of the State of Maine on the wall there and immediately fell to examining our town for soil type. What I found was as shocking as it was immediately recognizable: The map legend depicted our farm and the cemetery as sitting on glacial till–remnants of the last giant glacier to pulverize North America, the Laurentide Ice Sheet, up to about 12,000 years ago.

“No effing wonder,” I thought, “whole chunks of Canada lie here.”

*

One time, I had dug down a full foot before striking a big honking boulder with my spade, a frigging glacial erratic if there ever was one. “Oh, you miserable son of a bitch,” I said, quoting my dad (1934-2022). On one side was the concrete footing that had been poured in advance of the headstone’s arrival, and if I tried to remove the rock with an iron pry bar, it might upset the footing. So, I had to stop digging, probe to the edge of the boulder, and restart the grave about eight inches further in. When I had finished, it ended up being a sort of stepped grave, with a ledge formed by the rock twelve inches down.

Sitting in my truck later during the funeral, I noticed that the wife herself placed the urn into the grave, stepping down into the hole, putting her foot on that big rock below the surface, and leaning over to settle the urn on the bottom of the hole. As people were dispersing, I drove over to finish the burial, when the bereaved wife came up to me and said, “I want to thank you for putting that stair step in. It really made placing his ashes inside much easier.” I just shrugged and smiled.

But that’s not the funniest part: A few weeks later, the stone marker finally arrived, the one the footing had been poured for; and when I went over to inspect it, I found it engraved with the following inscription:

S T A I R W A Y T O H E A V E N

*

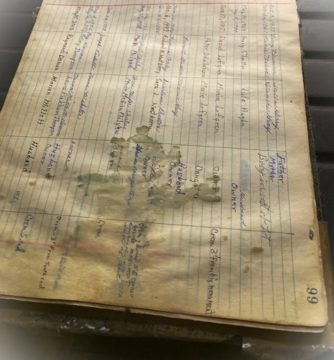

After receiving notice from a funeral director that a full service and burial will take place at our cemetery, I get a call from the deceased man’s nephew asking about the location of the grave. I get out the old burial records book I have inherited from the previous superintendent–an ancient, yellowed ledger held together by packing tape that we call The Bible–and look it up. When I tell him where the burial will be, he gets quiet a moment then asks, “Is that my family’s plot?”

“Yes. Your father gave permission for your uncle to be buried next to his sister.”

The sister was mother of the man on the phone now. The father long ago bought a block of five lots when his wife died and had her interred there.

“Where is this in relation to my own wife’s grave?” the nephew asks.

“Beside it.”

Immediately, the nephew says, “I’m planning to have my own ashes go in with my wife. Is there a way I can get ownership of that lot?”

“You could buy it from your father. Or perhaps he will gift it to you.”

That is what eventually happens. I get a letter from the father stating that, as owner of the block of lots, he is granting lot X to his son. So, I draw up a new conveyance–a sort of land deed in miniature–and send it to the man via mail. Once he gets the conveyance, he calls me up and says, “Thanks for sending the paperwork. How much do lots cost? I want to buy a new one.”

I tell him that there are no more plots available in that row.

“I don’t care,” he says. “I want one in the new section of the cemetery.”

In the meantime, the uncle is interred in the family plot as planned, the works–full burial contracted out to professional gravediggers, concrete vault, funeral procession, ceremony, etcetera. I don’t have to do a thing except mark the spot. Let them deal with the boulders.

Afterwards, things begin happening quickly: The nephew picks out and purchases a lot in the undeveloped section of the cemetery, far from his family plot, and he immediately has a monument company come out and pour a concrete footing for a gravestone.

Then he calls me to ask how much it costs to exhume and rebury an urn. I’ve never done this before–it basically means digging two graves–but instead of charging for two, I tell him I would just charge for one and a half.

The monument company returns to the cemetery with their big truck, and using their crane they package up the deceased wife’s headstone and move it to the new location across the cemetery. I’m thinking, “Whatever.”

The man wants to be there when I rebury his wife’s ashes in the new lot. When the time comes for burial, it is just the nephew, the urn, the new hole, and two piles of dirt on a tarp–a tall pile of sand, silt and gravel beside a heap of loam. The man silently weeps when I place his wife’s urn in its hole.

Afterward, I ask him if he has plans for the old lot, the one he gained ownership of next to his uncle but that now lies empty.

“I don’t care what happens to it,” the nephew says, “as long as we’re far away from that son of a bitch.”

*

The sisters, both in their sixties, have come up to Maine from Arizona with their mother’s urn to have her interred with her second husband. There is just the three of us, on a clear day in May, in the midst of the pandemic. We don’t wear masks as we’re in the open air. Just to make conversation before the inurnment, I look down at the veterans marker and ask, “Was Clyde from this area?”

“I don’t know,” one woman says. She glances to her sister, who says, “Don’t look at me.” This sister looks down at the urn in her hands and says, “I don’t know why she wanted us to bring her all the way up here.” She hands the urn to the other sister and eventually walks off to go sit in their rental car.

The remaining sister says, “Mom died of covid in the nursing home. Could you write up a receipt for the burial? We can get funeral assistance from the government.”

“Of course,” I say. “I’ll just need your mailing address.”

I take the hemlock bough-covered plywood cap off the grave. Every time I look into one of these holes I wonder if I’m next.

“This is your moment,” I say. “Is there anything you want to do, or anything you want me to do?”

The sister looks around the cemetery. It’s a perfect day, sunny, Clyde’s American flag waves in the breeze. She glances toward the car with her sister in it. Then she hands me the urn and says, “Plant her.”

*

I always manage to send a silent “Hello” to Don and Effie whenever I mow over their graves. They were my husband’s longest-lived neighbors, from families that go back centuries in the state of Maine. I had known them since I moved here in 1985: Their house was right across the street so that their kitchen window looked directly out onto our driveway and dooryard.

Effie (Ethelyn) was a homebody who never went out. It was a project for Don to get her out to her favorite antiques auctions and to relatives’ places. She was diminutive, bespectacled, and always had a sweater draped over her back and shoulders. Don was a social butterfly: He “opened” the local diner every morning after he retired and was a sort of kindly gossip-central for the neighborhood. After breakfast, he would come home, grab our newspaper out of our box, and sit with my husband and me in the kitchen as we ate breakfast, ratchet-jawing and laughing the morning away.

Effie was the first to go. As I was an EMT for about fifteen years, Don called me over whenever there was a problem. Effie had fainting spells, and once Don himself suffered a stroke (from which he fully recovered), and he would call my cell phone instead of dialing 911 directly. I had taken a long leave of absence from rescue work to manage our small farm and orchard venture, but I held onto my radio and kept track of calls. One November night, Don called me and said: “Mikey, Effie is on the kitchen floor.”

“Did you call rescue?”

“No.”

I got out my radio and summoned the ambulance immediately. I ran next door and found Effie on her back on the floor, not breathing. No heartbeat, either.

“Don,” I said, “go out to the end of your driveway and make sure to direct the ambulance in here when they arrive.” Actually, I wanted him out of the house as I did CPR on his wife.

Somehow, I continued rescue breathing and chest compressions on my neighbor until the ambulance arrived. I told my colleagues on the crew about her history, and off they went. I later heard they got her rhythm back in the back of the ambulance, but Effie died the next morning in the hospital in Portland. As this was several years before I started working at the cemetery, the former superintendent arranged her full interment. I never returned to the rescue crew: I turned in my gear after my spouse had a stroke; so I always referred to Effie as “my last rescue call.”

Don was a chain-smoker who, remarkably, lived to be 88, in spite of his stroke and bouts with bladder cancer. Just before covid struck, he developed liver cancer and was able to die at home surrounded by neighbors, his daughter, and nurses. I had just started working at the cemetery and was able to bury his urn myself, right on top of his wife’s vault. I returned the money for the burial to his daughter when I discovered that the dirt was so loose on his wife’s vault, and the top of the vault was so close to the surface of the ground, that I hardly had to do any work to inurn Don.

Every trip with the lawn mower over their flat markers is a moment of remembrance for dear, lost friends. To my husband, losing these neighbors was scarring, as it meant the Old Maine he had known since the 1970s was finally dead and gone.

*

A woman who is part of a funeral party asks if her grandson may help bury her daughter’s ashes. I have gotten such requests before, so I say, “Of course,” and head up to the grave site with my truck and shovels once the service is over.

I recall the first time a kid wanted to participate in a burial. This was at another small, private gathering over an elderly woman’s gravesite, an inurnment. When I showed up to close the grave, a preadolescent African American girl stepped forward with her white mother to ask if she could help. It was a delight to have this young girl, decked out in her sparkly purple dress and matching sparkling shoes, take up a shovel to help me. The shovel was almost as tall as she was, so I realized I would be doing the work while helping her direct shovelfuls of dirt into the grave. She stomped the shovel into the sand and gravel earnestly with her purple shoe and managed to assist me until the grave was filled.

“Thank you for letting me help,” she said, handing the shovel back to me.

“You’re welcome,” I said. Then I added, “You will always remember this,” hoping to help solidify an important moment in her young mind.

I expected something similar this time around, a boy wanting to participate as best he could in this oldest of human rites. The mother’s death in a car accident had occurred the previous summer. The family had retained the ashes until the time for burial was right for them. I thought this should be a pretty routine inurnment. I did not realize what I was in for. This would be a much different experience than the one with the little girl, by an order of magnitude.

When I arrived at the site, all vehicles had departed except for one. I drove my truck up the access road near the grave, got out and met the son. He was not a boy, but a young man in his twenties. His grandmother stood by, dressed in a casual long skirt, hair pulled back, glasses, looking very matronly. The surviving son was tall, dressed in shorts (it was terribly hot that day, and thunderstorms threatened that afternoon) and big sneakers. He had a head of magnificently mussed chestnut curls. He sniffled, and his mouth hung open as if he had a terrible cold. I shook his hand, said I would help him with the burial, and when he looked at me, I saw eyes swollen and red from crying. He looked exhausted. It was obvious to me that those twelve months since his mother died had not really passed at all. This is what inconsolable looks like, I thought.

I handed him the shovel, got out a two-by-four for myself, and explained that I would tamp down the dirt he put in, one shovelful at a time, so that the grave would not collapse later. He picked up gravel and sand with the shovel languidly, as if contemplating it, and moved it to the hole. We worked silently; there was just the sound of dirt hitting the top of the urn, the thumping of the two-by-four as I packed the dirt around it. At three-quarters full, I directed him to begin moving shovelfuls of loam to the hole. Not two feet away from where we labored, in the same lot, lay the remains of the deceased woman’s older sister, an aunt the young man beside me had never met, who had died thirty-some years previously. Yet another pit of sorrow–generations of it–in the glacial till.

The grandmother, mother of the two deceased daughters, stood by observing, arms folded across her bosom, as if she were clutching the boy himself against her chest.

When we had filled the grave, I put the square of sod back into place, and the young man instinctively helped me lift the tarp full of excess sand and gravel onto the tailgate of my truck. It was all over in ten minutes. There was something perfect about it: a silent, grave task done, without a hitch. I slammed the tailgate shut. The son turned back to stand over the now-covered grave.

What could I say? The young man burying a mother cut down in the middle of her life is not like the young girl burying a grandmother who has lived a full life. To say to him, You will always remember this, would sound shockingly callous, even insane. I could state the truth: You know this world is shittier than we can imagine when you have to fit an entire parent into a small hole. But he already knows that. Much more than I do. My father died last summer at age 86, fully twice this young man’s mother’s age. Yet the grief I witnessed that afternoon was a natural wonder to me: I was three times the kid’s age but never had to stomach such loss.

“It has been an honor to help you with this,” I said. Because, indeed, he had done the work of burying the dead. He didn’t respond. “I don’t think he heard me,” I said, looking at his grandmother.

She called out his name. The bereaved son’s head snapped up. I stepped forward and extended my hand. “It has been an honor to help you with this,” I repeated. He took my hand and gazed at me with eyes still raw with grief.

*

I feel a need to end with some graveyard levity. Here’s a sort of inverted “knock-knock” joke set in a cemetery: you have to start it:

You: Knock-knock.

Me: [Silence.] I don’t think anyone heard you.

You: Knock-knock.

Me: Louder! You have to wake the dead!

You: Knock! Knock!

Me: Go away! Nobody lives here!

_____________________

The details of these episodes are factual, but in a few of these I have combined multiple incidents and obscured identities to protect privacy.

Images by the author.