by Mike Bendzela

I am a sort of “coincidence theorist”: I think most shit just happens, and our human duty is to be simultaneously appalled and amused by it all. The first gay man I ever met, who died of AIDS in 1985, was of the opposite temperament. He often told me “there are no coincidences” (his attempt, I think, to unnerve naive, Midwestern me). “The universe has a sway to it,” he used to say. He was a mystic who read Tarot cards and cast horoscopes for people, but I wanted nothing to do with any of that. Such a mindset suggests my friend must have died of AIDS “for a reason.” This view is repugnant to me, with its constant, cosmic vigilance bordering on paranoia.

The fact that the deaths I am about to describe all transpired during the covid years (2020-2022) is just that, coincidence. One of the benefits of writing nonfiction is you get to indulge the “you couldn’t make this stuff up if you tried” trope. It sometimes seems the more implausible events are, the more likely they are to be true. As Tim O’Brien puts it in his fictional accounting of the “true war story”:

In many cases a true war story cannot be believed. If you believe it, be skeptical. It’s a question of credibility. Often, the crazy stuff is true and the normal stuff isn’t, because the normal stuff is necessary to make you believe the truly incredible craziness.

At the outset of the pandemic in early 2020, people my husband and I knew suddenly began to die. Shortly after, I began to notice that I was losing my sense of smell. The first casualty, a favorite neighbor, was in his late 80s and had succumbed to a longtime struggle with cancer. I would bury his ashes that summer in the neighborhood cemetery I take care of. It was like burying a family member; I had known him for 35 years. As the pandemic was still pretty new and mysterious, those of us gathered at the cemetery stood around in the broad daylight crying behind surgical masks. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Night Seagulls at Karachi Harbor, Dec 7, 2023.

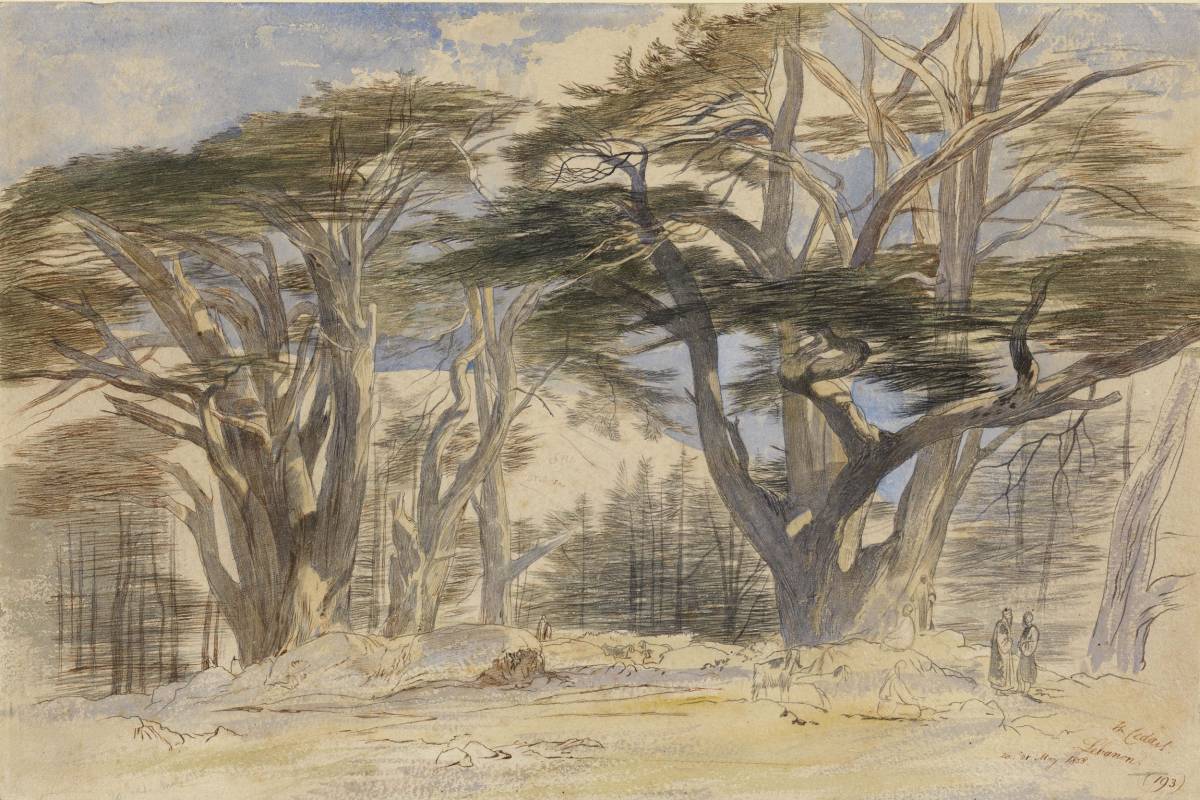

Sughra Raza. Night Seagulls at Karachi Harbor, Dec 7, 2023. The philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote in The Nicomachean Ethics that you cannot become good without practice. Even the ideal utterly good person whose every action is carried out at the right time for the right reason, has gone through a long process of trial and error; their ultimate victory over bad tendencies, precipitous judgement and external obstacles is a victory achieved through blood, sweat and tears. Aristotle’s promise is that the effort that engages both body and mind– if carried through with constancy and a bit of luck – will some day be sublimated into a way of being which will become both effortless and wholly constitutive of the moral agent. True enough, this ideal remains somewhat shrouded in the mist of a far-away horizon, but the path is paved, however arid and mountainous it may be. With the help of guides and maps, models and teachers, it is up to us to commit to the daunting effort.

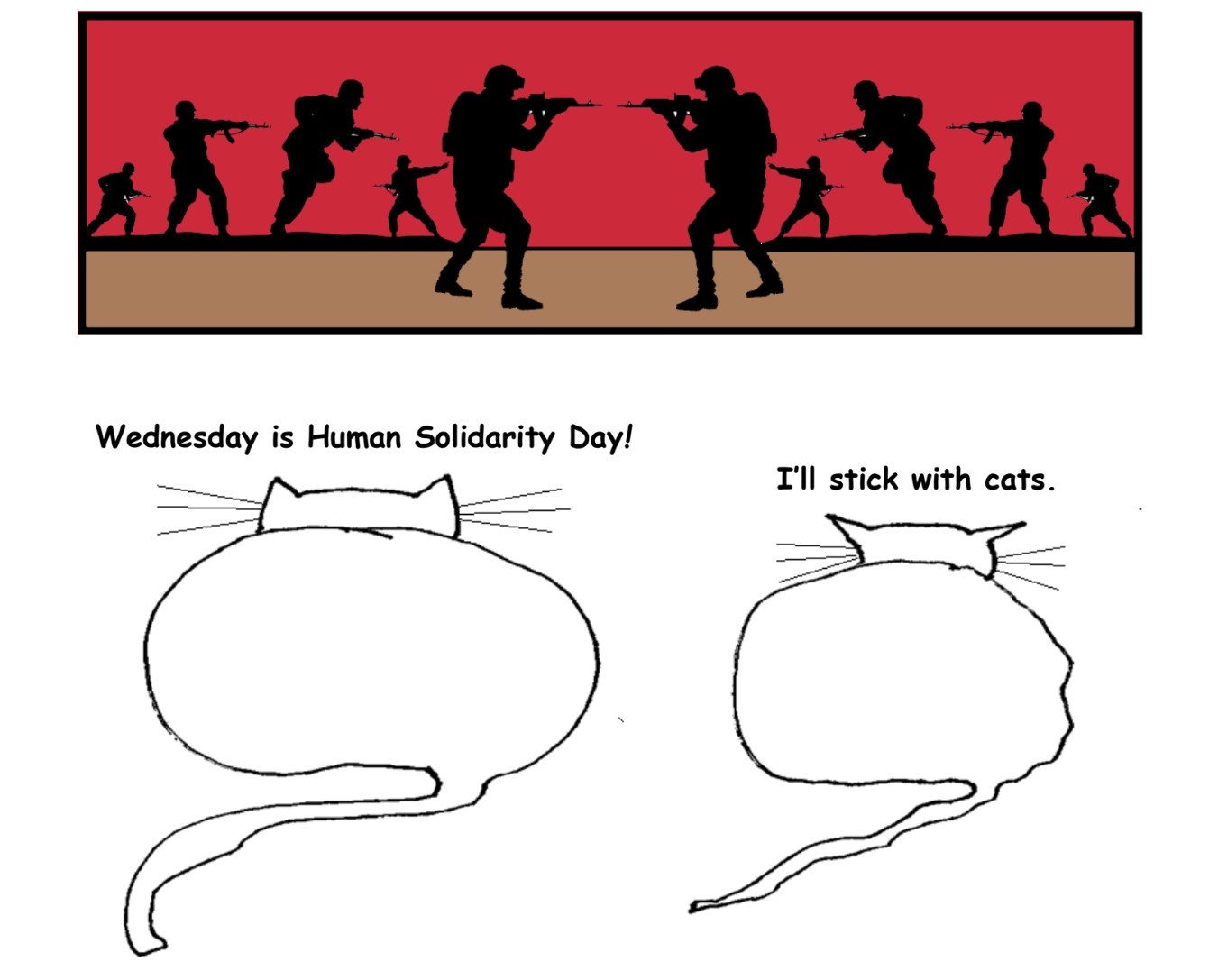

The philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote in The Nicomachean Ethics that you cannot become good without practice. Even the ideal utterly good person whose every action is carried out at the right time for the right reason, has gone through a long process of trial and error; their ultimate victory over bad tendencies, precipitous judgement and external obstacles is a victory achieved through blood, sweat and tears. Aristotle’s promise is that the effort that engages both body and mind– if carried through with constancy and a bit of luck – will some day be sublimated into a way of being which will become both effortless and wholly constitutive of the moral agent. True enough, this ideal remains somewhat shrouded in the mist of a far-away horizon, but the path is paved, however arid and mountainous it may be. With the help of guides and maps, models and teachers, it is up to us to commit to the daunting effort.