by Nils Peterson

“…another kind of net, that language, the one the world gives us to cast so that we might catch in it a little of what it is and what we are, and we are, among other things, the poverties of the language we inherit.” Robert Hass, “Families and Prisons,” What Light Can Do.

These days when night and cold come so soon one wants nothing more than to huddle around a fire, read for awhile, then go to bed – but the world has its obligations.

I was walking the dog in the cold night air, almost remembering what I wanted to remember, and then it came to me, the opening paragraph of James Joyce’s “Araby.”

The first time I read it was magic, the feel and look of the winter air, the awareness of the intensity of one’s aliveness in it, and Mangan’s sister:

When the short days of winter came dusk fell before we had well eaten our dinners. When we met in the street the houses had grown sombre. The space of sky above us was the colour of ever-changing violet and towards it the lamps of the street lifted their feeble lanterns. The cold air stung us and we played till our bodies glowed. Our shouts echoed in the silent street. The career of our play brought us through the dark muddy lanes behind the houses, where we ran the gauntlet of the rough tribes from the cottages, to the back doors of the dark dripping gardens where odours arose from the ashpits, to the dark odorous stables where a coachman smoothed and combed the horse or shook music from the buckled harness. When we returned to the street, light from the kitchen windows had filled the areas. If my uncle was seen turning the corner, we hid in the shadow until we had seen him safely housed. Or if Mangan’s sister came out on the doorstep to call her brother in to his tea, we watched her from our shadow peer up and down the street. We waited to see whether she would remain or go in and, if she remained, we left our shadow and walked up to Mangan’s steps resignedly. She was waiting for us, her figure defined by the light from the half-opened door. Her brother always teased her before he obeyed, and I stood by the railings looking at her. Her dress swung as she moved her body, and the soft rope of her hair tossed from side to side.

Yes, the paragraph described me too, though I was far in time and space from “dark odorous stables.” (Actually, there were some old stables around where I lived then, used for garages for awhile, but now mostly storage sheds filled with mysterious things.)

Then I remembered the girl next door, a year or two older than I who had once been the babysitter for me and my brother, but when I had caught up a little bit, passed puberty, and we were both going to high school, she walked ahead of me all the way while I shuffled behind and never said a word. But I certainly thought of her in my own way. Read more »

“In bardo again,” I text a friend, meaning I’m at the Dallas airport, en route to JFK. I can’t remember now who came up with it first, but it fits. Neither of us are even Buddhist, yet we are Buddhist-adjacent, that in-between place. Though purgatories are not just in-between places, but also places in themselves.

“In bardo again,” I text a friend, meaning I’m at the Dallas airport, en route to JFK. I can’t remember now who came up with it first, but it fits. Neither of us are even Buddhist, yet we are Buddhist-adjacent, that in-between place. Though purgatories are not just in-between places, but also places in themselves.

Do corporations have free will? Do they have legal and moral responsibility for their actions?

Do corporations have free will? Do they have legal and moral responsibility for their actions?

Stephanie Morisette. Hybrid Drone/Bird, 2024.

Stephanie Morisette. Hybrid Drone/Bird, 2024.

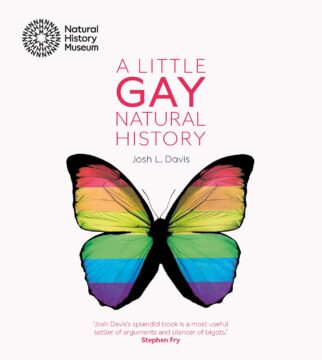

In his inaugural speech on 20 January 2025, Donald Trump jumped into the fray on the contentious issues of gender identity and sex when he announced that his administration would recognise “only two genders – male and female”. At this point there is no conceptual clarity on his understanding of the contested issues of ‘gender’ and ‘male and female’, but we do not have to wait too long before he clarifies his position. His executive order, ‘Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremists and Restoring Biological Truth to Federal Government’ signed by him soon after the official formalities of his inauguration were completed, sets out the official working definitions to be implemented under his administration.

In his inaugural speech on 20 January 2025, Donald Trump jumped into the fray on the contentious issues of gender identity and sex when he announced that his administration would recognise “only two genders – male and female”. At this point there is no conceptual clarity on his understanding of the contested issues of ‘gender’ and ‘male and female’, but we do not have to wait too long before he clarifies his position. His executive order, ‘Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremists and Restoring Biological Truth to Federal Government’ signed by him soon after the official formalities of his inauguration were completed, sets out the official working definitions to be implemented under his administration.