by David M. Introcaso

Over the past several months the White House has taken several significant steps to undermine our nation’s ability to mitigate climate change or global warming. While these policies are being rolled out the increasingly dramatic effects of anthropogenic climate change are taking place before our eyes. Because there has always been a link between climate and health the obviously begged question is what has been the professional medical community’s response to all this?

The Past Few Months

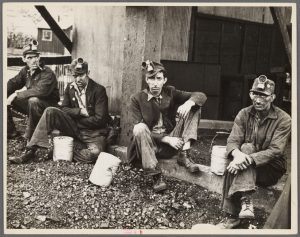

The US is the biggest carbon polluter in history. Regardless, this past March the President Trump issued his Executive Order (EO) On Energy Independence the White House press shop stated, “stops Obama’s war on fossil fuels.” Among other things, the EO allows the EPA to review President Obama’s Clean Power Plan initiative aimed at reducing carbon pollution or greenhouse gas emissions from coal plants by 32 percent of 2005 levels by 2030. (Carbon dioxide, that accounts for approximately 60 percent of greenhouse gasses, has increased by 40 percent since pre-industrial levels and more than half of this increase has occurred over the past three decades.) The EO also lifted a 14 month moratorium on new coal leases on federal lands and it eliminates guidance that climate considerations be factored into environmental reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

Two months later or on June 1st President Trump announced the US would withdraw from the Paris climate accord signed by 194 other nations and considered by many to be modestly ambitious. US joined Syria as the only non-participant. (Nicaragua also refused to sign because its envoy said the accord was insufficiently ambitious.) Under the accord the US had committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 26 to 28 percent compared to 2005 levels by 2025. Trump’s decision was made despite the fact the president’s Secretary of State, and former Exxon CEO, Rex Tillerson, opposed the decision. Ironically, in early May Tillerson signed the Fairbanks Declaration that stressed the importance of reversing Arctic warming that is occurring at twice the rate of the global average and has caused to date the disappearance of 40 percent of summer Arctic ice. Following up on the President’s March EO, EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt, announced in early October his agency would begin the process of repealing the Clean Power Plan. Most recently, or on November 3rd, the Trump administration, surprisingly, released a Congressionally-mandated report assessing climate change. (The report’s release was expected in August.) Authored by 13 federal agencies and considered the most definitive statement on the subject, the report titled, “‘US Global Change Research Program, Climate Science Special Report” (CSSR), stated in part, “it is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominate cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century.” The White House played down the reports findings stating “the climate has changed and is always changing.”