by Abigail Akavia

As was to be expected, artists are now calling to relocate the next Eurovision Song Contest, which is to be held in Israel in May. No less predictably, supporters are saying, more or less, “let’s leave politics out of it”. As if the Eurovision is nothing but a celebration of music, a friendly competition where sportsmanship is what counts above else. As if, indeed, athletic competitions have nothing to do with politics. The Eurovision has been described as the “Gay Olympics” or the “Gay World Cup.” The analogy brings to mind the controversies surrounding Russia’s hosting of the 2018 world cup games, despite the country’s well-documented violations of human rights. The example of Russia is telling, since there was quite a lot of criticism aimed at FIFA this summer, not for allowing Russia to host per se, but for failing to secure the games as a racism-free zone. In the 2014 Eurovision held in Copenhagen, the Russian representatives were loudly booed in response to Russia’s recent annexation of Crimea and its stance on gay rights. Like it or not, Eurovision participants are held as representatives of their nation, and are judged as such. Thus, even though Eurovision fans display a “playful nationalism” in their celebratory participation in the events, and often support not only their nation’s song but also the one they deem most worthy, the Eurovision remains an overt political arena where two issues are at stake: nationalism and queerness.

A local controversy surrounding one of the runner-ups to become Israel’s contestant to the Eurovision illuminates these two contexts and how they intersect. The next performer to represent Israel on the Eurovision Song Contest will be chosen in a pre-competition reality show called “The Next Star.” Since the competition began two and half months ago, one of the contestants has gained particular attention. Rotem Shefi, a Jewish Israeli singer, performs under the stage-persona of Shefita, an Arab diva, whose props include tacky gowns, heavy jewelry, a glittery walking-cane (yup), and, the most important in her toolbox, a thick Arabic accent. Shefi’s songs in the competition have so far been almost exclusively covers, remakes of rock and pop hits rendered in a non-specific Middle Eastern, pseudo-Arabic sound, performed in English. Despite some signs of unease, especially among one of the show’s judges, Shefita is consistently voted up, and is still presented as a likely contender to win and become Israel’s representative to the Eurovision. Read more »

Like most people of a certain age, at any one time I have the unfortunate experience of knowing several people, some close, some not, who have cancer. It has become standard for the friend or spouse of the ill person to join one of the many message boards devoted to the subject and post updates to keep their friends and relatives informed. Others use Facebook to share information. Currently there are three people whose lives I follow, mostly from a distance, all with serious forms of cancer, one newly diagnosed but metastasized, two others who have been fighting for months and months.

Like most people of a certain age, at any one time I have the unfortunate experience of knowing several people, some close, some not, who have cancer. It has become standard for the friend or spouse of the ill person to join one of the many message boards devoted to the subject and post updates to keep their friends and relatives informed. Others use Facebook to share information. Currently there are three people whose lives I follow, mostly from a distance, all with serious forms of cancer, one newly diagnosed but metastasized, two others who have been fighting for months and months.

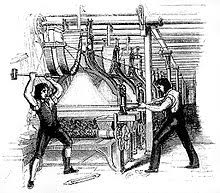

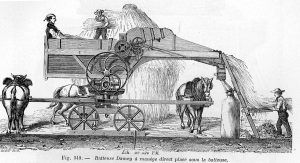

“Luddite” is a word that is thrown around a lot these days. It signifies someone who is opposed to technological progress, or who is at least not climbing on board the technological bandwagon. 21st century luddites tend to eschew social media, prefer presentations without PowerPoint, still write cheques, and may even, in extreme cases, get by without a cell phone. When used in the first person, “luddite” is often a badge of honour. “I’m a bit of a luddite,” usually means “I see through and am unimpressed by the false promise of constant technological novelty.” Used in the third person, though, it typically suggests criticism. “So-and-so’s a bit of a luddite,” is likely to imply that So-and-so finds the latest technology confusing and has failed to keep up with it, probably due to intellectual limitations.

“Luddite” is a word that is thrown around a lot these days. It signifies someone who is opposed to technological progress, or who is at least not climbing on board the technological bandwagon. 21st century luddites tend to eschew social media, prefer presentations without PowerPoint, still write cheques, and may even, in extreme cases, get by without a cell phone. When used in the first person, “luddite” is often a badge of honour. “I’m a bit of a luddite,” usually means “I see through and am unimpressed by the false promise of constant technological novelty.” Used in the third person, though, it typically suggests criticism. “So-and-so’s a bit of a luddite,” is likely to imply that So-and-so finds the latest technology confusing and has failed to keep up with it, probably due to intellectual limitations.

The traffic had been slow all day but by four pm, it was reduced to a trickle. Those cars that passed him on the street did so in two and threes as if they were sticking together for safety like lumbering animals caught out in a storm. It was, in fact, a very harsh winter day. The afternoon temperatures dipped well below zero: one of the coldest days ever recorded in Chicago. The only sounds now were from an occasional plane passing overhead, and from distant cackling from those venturesome neighbors who had left snug homes to experience the cold. He could hear the sound of his feet crunching through the snow.

The traffic had been slow all day but by four pm, it was reduced to a trickle. Those cars that passed him on the street did so in two and threes as if they were sticking together for safety like lumbering animals caught out in a storm. It was, in fact, a very harsh winter day. The afternoon temperatures dipped well below zero: one of the coldest days ever recorded in Chicago. The only sounds now were from an occasional plane passing overhead, and from distant cackling from those venturesome neighbors who had left snug homes to experience the cold. He could hear the sound of his feet crunching through the snow. One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism.

One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism. The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As

The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As  A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with

A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with  In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1