by Bill Murray

OUTBOUND

We’re off to meet a small live-aboard motorboat about three hours drive south of Ho Chi Minh City to cruise the Mekong Delta for a few days. The older gentleman driving has a deep, rich voice we don’t understand, speaks no English and we no Vietnamese besides pleasantries, the names of some food and a particular local beer, 333, not very challengingly pronounced baa baa baa, like the black sheep.

He’s a pro driver, no doubt about that, all turned out in a nice golf shirt and slacks, and he works our little sedan to the Saigon River then south out of town, and holds a steady course until the city falls away. He appropriates the left lane and proceeds with zealous caution, a campaign strategy he follows every bloody deliberate inch of the way.

Steady ahead. If he hurtles inadvertently to 60 kph, even on long, empty stretches, his face flushes and he brakes abruptly. Could he be working by the hour? If they say this trip should take three and a half hours, no way will he make it three hours and a quarter.

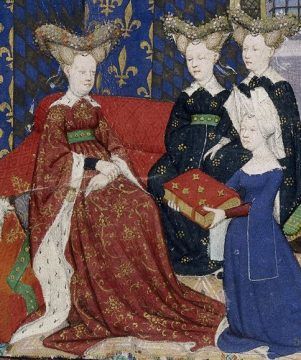

We first came to Saigon twenty-five years ago. Since then women have largely dispensed with the demure way they rode the back of cycles, both legs to one side. Back then many more women wore the traditional Ao Dai, the thin, body length robe. Perhaps that made it hard to sit any other way.

The river yields to a web of canals. Smart electronic overhead signs show the way through less kempt industrial outskirts. Now we roll along a divided six-lane highway, with extra outside lanes for every variety of two-wheeler, and this goes on for miles and undifferentiated miles. Read more »

Madeleine LaRue: It did turn out to be pretty mammoth! How about I tell you, by way of introduction, about the first time I met Bichsel in person. He’d come to read at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin, the center of the grand old West Berlin literary establishment. It was November, it was dark and cold, and when he emerged at the back of the room and started walking up toward the stage, wearing the same black leather vest he’s been wearing for the past forty years, I think we were all a little worried about him. He was eighty-two then, and he looked exhausted. It had been a while since he’d been on such an extensive reading tour outside of Switzerland. He got to the stage and settled into his chair. The moderator welcomed him and asked how it felt to be back in Berlin—a simple question, a nice, easy opener. Bichsel still seemed tired, but as he leaned back and said, very slowly, in his lilting Swiss accent, “Ja, ja, Berlin,” his eyes lit up and he launched into a story about his first time in the city, in the early 1960s, and how he got caught in the middle of a bar fight with some people! Who turned out to be Swiss! And they all got thrown out onto the street together, and he’ll never forget it! And ja, ja, Berlin—and from his very first word, we all became like delighted children at Grandfather’s feet, totally enraptured, utterly unwilling to go to bed until we’d heard just one more story, pleeeease? And he himself became younger, full of life, charming and hilarious and genuine and profound.

Madeleine LaRue: It did turn out to be pretty mammoth! How about I tell you, by way of introduction, about the first time I met Bichsel in person. He’d come to read at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin, the center of the grand old West Berlin literary establishment. It was November, it was dark and cold, and when he emerged at the back of the room and started walking up toward the stage, wearing the same black leather vest he’s been wearing for the past forty years, I think we were all a little worried about him. He was eighty-two then, and he looked exhausted. It had been a while since he’d been on such an extensive reading tour outside of Switzerland. He got to the stage and settled into his chair. The moderator welcomed him and asked how it felt to be back in Berlin—a simple question, a nice, easy opener. Bichsel still seemed tired, but as he leaned back and said, very slowly, in his lilting Swiss accent, “Ja, ja, Berlin,” his eyes lit up and he launched into a story about his first time in the city, in the early 1960s, and how he got caught in the middle of a bar fight with some people! Who turned out to be Swiss! And they all got thrown out onto the street together, and he’ll never forget it! And ja, ja, Berlin—and from his very first word, we all became like delighted children at Grandfather’s feet, totally enraptured, utterly unwilling to go to bed until we’d heard just one more story, pleeeease? And he himself became younger, full of life, charming and hilarious and genuine and profound.  Having before you an iced mango

Having before you an iced mango

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

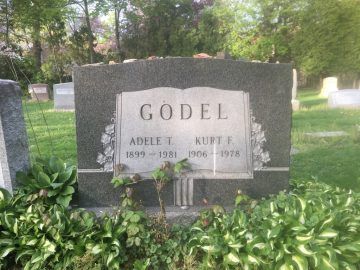

On a whim I decided to visit the gently sloping hill where the universe announced itself in 1964, not with a bang but with ambient, annoying noise. It’s the static you saw when you turned on your TV, or at least used to back when analog TVs were a thing. But today there was no noise except for the occasional chirping of birds, the lone car driving off in the distance and a gentle breeze flowing through the trees. A recent trace of rain had brought verdant green colors to the grass. A deer darted into the undergrowth in the distance.

On a whim I decided to visit the gently sloping hill where the universe announced itself in 1964, not with a bang but with ambient, annoying noise. It’s the static you saw when you turned on your TV, or at least used to back when analog TVs were a thing. But today there was no noise except for the occasional chirping of birds, the lone car driving off in the distance and a gentle breeze flowing through the trees. A recent trace of rain had brought verdant green colors to the grass. A deer darted into the undergrowth in the distance.

Sughra Raza. Enlightened, April, 2019.

Sughra Raza. Enlightened, April, 2019.