by Emrys Westacott

The relation between what is natural and what is morally good is a topic that has concerned philosophers from ancient times to the present. Those who view the part of a human being that belongs to the material world as sordid, unclean, and irrational have understood morality to require the suppression or the taming of nature; the angel in us must control the beast. This outlook is endorsed by Plato and is commonly found in Christian theology. Hobbes’ social contract theory, which presents moral life and political order as the way we escape the miseries of the state of nature, also takes morality and nature to be in certain respects opposed. Many others, though, have looked to nature for some sort of moral guidance. The Stoics viewed the implacable order observed in the heavens as a model for a serene human life. Defenders of rigid social hierarchies pointed to the successful arrangements in a bee hive. Critics of homosexuality argue that it is “unnatural,” while advocates of gay rights deny this. Appeals to what one finds in nature have bolstered social Darwinism, the subordination of women, arguments for and against slavery, egalitarianism, and the idea of universal human rights.

The relation between what is natural and what is morally good is a topic that has concerned philosophers from ancient times to the present. Those who view the part of a human being that belongs to the material world as sordid, unclean, and irrational have understood morality to require the suppression or the taming of nature; the angel in us must control the beast. This outlook is endorsed by Plato and is commonly found in Christian theology. Hobbes’ social contract theory, which presents moral life and political order as the way we escape the miseries of the state of nature, also takes morality and nature to be in certain respects opposed. Many others, though, have looked to nature for some sort of moral guidance. The Stoics viewed the implacable order observed in the heavens as a model for a serene human life. Defenders of rigid social hierarchies pointed to the successful arrangements in a bee hive. Critics of homosexuality argue that it is “unnatural,” while advocates of gay rights deny this. Appeals to what one finds in nature have bolstered social Darwinism, the subordination of women, arguments for and against slavery, egalitarianism, and the idea of universal human rights.

In Against Nature, Lorraine Daston (Director of Berlin’s Max Planck Institute for the History of Science), poses the following question: “Why do human beings, in many different cultures and epochs, pervasively and persistently, look to nature as a source of norms for human conduct?”[1]The book belongs to the Untimely Meditation series published by MIT Press. At seventy pages, nine of which are taken up by illustrations, and four of which are blank, the book is essentially an 18,000 word essay on this topic.

The modern view of nature that emerged and took hold during the scientific revolution is that it contains no values. In the thought of intellectual pioneers like Descartes and Boyle, the material world is best understood as a vast machine operating predictably according to universal laws of nature. The implications of this outlook for ethics were first noticed by Hume when he observed that there is a logical difference between “is” statements that describe facts, and “ought” statements that express values; moreover, because of this logical difference, it is impossible to fully justify the latter by appealing to the former. Descriptions, by themselves, never logically entail prescriptions. Since then, the “fact-value gap” has haunted much moral philosophy. But even though John Stuart Mill and others have warned against using nature as a moral guide–think preying mantis and sexual relations–according to Daston, “the temptation to extract norms from nature seems to be enduring and irresistible.”[2] Read more »

The authority of scientific experts is in decline. This is unfortunate since experts – by definition – are those with the best understanding of how the world works, what is likely to happen next, and how we can change that for the best. Human civilisation depends upon an intellectual division of labour for our continued prosperity, and also to head off existential problems like epidemics and climate change. The fewer people believe scientists’ pronouncements, the more danger we are all in.

The authority of scientific experts is in decline. This is unfortunate since experts – by definition – are those with the best understanding of how the world works, what is likely to happen next, and how we can change that for the best. Human civilisation depends upon an intellectual division of labour for our continued prosperity, and also to head off existential problems like epidemics and climate change. The fewer people believe scientists’ pronouncements, the more danger we are all in.

Growing up, a lighter branded you as suspect to any Baptist worth his King James Version. Because really, other than smoking and setting houses on fire to incinerate the family within just for kicks, what did you need a lighter for anyway? If you wanted to light something righteous like a candle or the water heater, you reached for the box of safety matches next to the paprika in the spice cabinet. They had SAFETY written on the box in case you felt tempted to go astray. Lighters should have had Iniquity Equipment inscribed on them as far as we were concerned.

Growing up, a lighter branded you as suspect to any Baptist worth his King James Version. Because really, other than smoking and setting houses on fire to incinerate the family within just for kicks, what did you need a lighter for anyway? If you wanted to light something righteous like a candle or the water heater, you reached for the box of safety matches next to the paprika in the spice cabinet. They had SAFETY written on the box in case you felt tempted to go astray. Lighters should have had Iniquity Equipment inscribed on them as far as we were concerned.

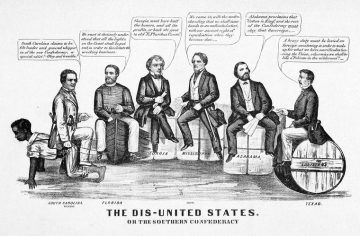

By the time Sherman’s armies had scorched and bow-tied their way to the sea, by the time Halleck had followed Grant’s orders to “eat out Virginia clean and clear as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their own provender with them,” and by the time Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was finished squeezing every drop of life out of the Confederacy, there had to be those who wondered what possible logic would lead intelligent men like Jefferson Davis to make such a catastrophic choice.

By the time Sherman’s armies had scorched and bow-tied their way to the sea, by the time Halleck had followed Grant’s orders to “eat out Virginia clean and clear as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their own provender with them,” and by the time Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was finished squeezing every drop of life out of the Confederacy, there had to be those who wondered what possible logic would lead intelligent men like Jefferson Davis to make such a catastrophic choice.

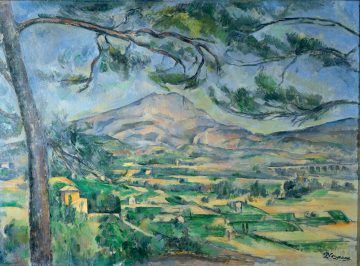

Philosophers have spilled a great deal of ink attempting to nail down once and for all the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing’s being a work of art. Many theories have been proposed, which can seem in retrospect to have been motivated by particular works or movements in the history of art: if you’re into Cézanne, you might think art is “significant form,” but if you’re impressed by Andy Warhol, you might that arthood is not inherent in a work’s perceptible attributes, but is instead something conferred upon it by members of the artworld.

Philosophers have spilled a great deal of ink attempting to nail down once and for all the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing’s being a work of art. Many theories have been proposed, which can seem in retrospect to have been motivated by particular works or movements in the history of art: if you’re into Cézanne, you might think art is “significant form,” but if you’re impressed by Andy Warhol, you might that arthood is not inherent in a work’s perceptible attributes, but is instead something conferred upon it by members of the artworld.

logician of modern times, at Einstein’s urging, brought his two magnificent proofs to Princeton. There he would remain for almost forty years, never mentoring a graduate student, rarely lecturing, adding only one substantial but incomplete proof to the cannon of math.

logician of modern times, at Einstein’s urging, brought his two magnificent proofs to Princeton. There he would remain for almost forty years, never mentoring a graduate student, rarely lecturing, adding only one substantial but incomplete proof to the cannon of math.

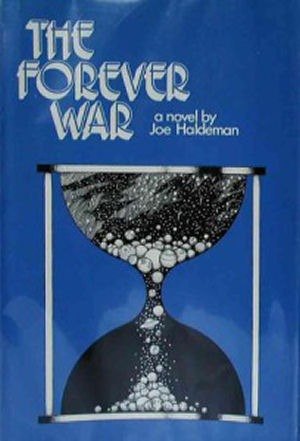

In 1974, noted science fiction author Joe Haldeman published a novel called The Forever War, which won several awards and spawned sequels, a comic version, and even a board game. The Forever War tells the story of William Mandella, a young physics student drafted into a war that humans are waging against an alien race called the Taurans. The Taurans are thousands of light years away, and traveling there and back at light speed leads Mandella and other soldiers to experience time differently. During two years of battle, decades pass by on Earth. Consequently, the world Mandella returns to each time is increasingly different and foreign to him. He eventually finds his home planet’s culture unrecognizable; even English has changed to the point that he can no longer understand it.

In 1974, noted science fiction author Joe Haldeman published a novel called The Forever War, which won several awards and spawned sequels, a comic version, and even a board game. The Forever War tells the story of William Mandella, a young physics student drafted into a war that humans are waging against an alien race called the Taurans. The Taurans are thousands of light years away, and traveling there and back at light speed leads Mandella and other soldiers to experience time differently. During two years of battle, decades pass by on Earth. Consequently, the world Mandella returns to each time is increasingly different and foreign to him. He eventually finds his home planet’s culture unrecognizable; even English has changed to the point that he can no longer understand it.