by Joan Harvey

a skilled

Vigilant, flexible,

Unemphasised, enthralled

Catching of happiness

from Born Yesterday by Philip Larkin, quoted in Adam Phillips, One Way and Another

But the fear’s so strong it leaves you gasping

No way to last out here like this for long

‘Cause everywhere I go, I know

Everywhere I go, I know

All my happiness is gone

All my happiness is gone

It’s all gone somewhere beyond

All my happiness is gone

—David Berman, All My Happiness is Gone

It’s tied to that word we were talking about this morning—ebbrezza. There is a sort of wondrous fever that can go on, and that is very near a feeling of happiness. The Sanskrit word tapas, “ardor,” is deeply connected with this. —Roberto Calasso

In Microhabitat, a film by Korean Jeon Go-woon, a young woman who cleans houses for a living goes to an elegant bar after work each day where she sits alone and contemplatively drinks a glass of good whiskey and smokes a cigarette. When her rent goes up, rather than give up this daily bit of relief she gives up her apartment, and moves nomadically around the city, staying with friends when she can. Some of her friends in the film are morally outraged at her choice, especially as neither cigarettes nor whiskey are considered healthy. I found the film striking in showing a woman taking care of herself, in a way not socially acceptable, knowing what she needed to get through the day. Men are often filmed in bars, but we rarely see women just pausing, not unhappy, not looking for anything but time alone for themselves, in a place where, for a change, they are waited upon. I saw in this a woman’s way of allowing herself some daily respite, an achievement of a space of happiness. Read more »

I remember the first time I thought I might be able to get on board with Stoicism. I read a

I remember the first time I thought I might be able to get on board with Stoicism. I read a

Do you remember when the Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw suggested significant changes to English spelling so that it would make more sense? Probably not, because it was more than 70 years ago. According to him

Do you remember when the Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw suggested significant changes to English spelling so that it would make more sense? Probably not, because it was more than 70 years ago. According to him

Things are changing. Always, everywhere, immensely and minutely, the history of mankind unfolds as we rotate around a grand burning star (also, everything everywhere else changes; the history of mankind may be of the least consequence on a cosmic scale, but I digress). I digress too early; I include parentheticals too soon; I stall with flowery descriptions of the sun. Because – ugh – I’m going to talk about “how divided we are as a nation.” It’s such a tired phrase; I don’t want to write about it. It’s stale because it’s static, and anyway, the declaration is often accompanied by divisive rhetoric. Wherever one may fall on the political spectrum (and here I’m being gracious; how often do we now identify with a “side”), they likely have established opinions of those who lie elsewhere. It does seem increasingly difficult to imagine a sweeping reconciliation when we continue to pour our definitions in concrete and defend our positions by reason of consistency. Inflexibility begets inability to listen, and thus to understand, which is why we find our differences so baffling and allow our prejudices to influence our opinions. So, finally, here it is: my own personal take on how we can get people to stop saying how divided we are. Bear with me, because I’m going to try and sell contradictions as potential energy for unity.

Things are changing. Always, everywhere, immensely and minutely, the history of mankind unfolds as we rotate around a grand burning star (also, everything everywhere else changes; the history of mankind may be of the least consequence on a cosmic scale, but I digress). I digress too early; I include parentheticals too soon; I stall with flowery descriptions of the sun. Because – ugh – I’m going to talk about “how divided we are as a nation.” It’s such a tired phrase; I don’t want to write about it. It’s stale because it’s static, and anyway, the declaration is often accompanied by divisive rhetoric. Wherever one may fall on the political spectrum (and here I’m being gracious; how often do we now identify with a “side”), they likely have established opinions of those who lie elsewhere. It does seem increasingly difficult to imagine a sweeping reconciliation when we continue to pour our definitions in concrete and defend our positions by reason of consistency. Inflexibility begets inability to listen, and thus to understand, which is why we find our differences so baffling and allow our prejudices to influence our opinions. So, finally, here it is: my own personal take on how we can get people to stop saying how divided we are. Bear with me, because I’m going to try and sell contradictions as potential energy for unity.

Firstly, of course we should rescue the art first. Secondly, of course we should not.

Firstly, of course we should rescue the art first. Secondly, of course we should not.

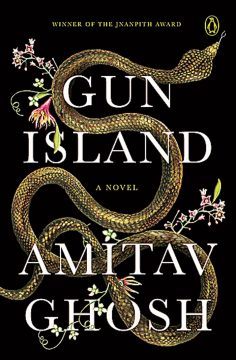

Following in the footsteps of the brilliant and exhaustive account of the British opium wars in his hefty Ibis Trilogy, Amitav Ghosh’s latest book Gun Island at just over 300 pages, is a relatively slim volume in which he returns to the Sundarbans to pick up from where his 2004 novel The Hungry Tide left off, with a dire warning about the ravaged ecological plight of the region. Only this time, Ghosh’s novel takes us out of the Sundarbans to Venice via Brooklyn, Kolkata and Los Angeles.

Following in the footsteps of the brilliant and exhaustive account of the British opium wars in his hefty Ibis Trilogy, Amitav Ghosh’s latest book Gun Island at just over 300 pages, is a relatively slim volume in which he returns to the Sundarbans to pick up from where his 2004 novel The Hungry Tide left off, with a dire warning about the ravaged ecological plight of the region. Only this time, Ghosh’s novel takes us out of the Sundarbans to Venice via Brooklyn, Kolkata and Los Angeles. A degree in engineering from India, grad school at an American university, and a job at an American corporation: call it the Indian-engineer version of the American dream. Like hundreds of thousands of Indian immigrants, Ved, the 36-year old protagonist of

A degree in engineering from India, grad school at an American university, and a job at an American corporation: call it the Indian-engineer version of the American dream. Like hundreds of thousands of Indian immigrants, Ved, the 36-year old protagonist of

Academic dishonesty is a widespread problem in colleges in many countries, and it is getting worse. One particular form of cheating has become especially common in the age of the internet: students buying custom-written essays–a.k.a. “contract cheating.” A recent study estimated that over 15% of college students had paid someone else to do their work for them;

Academic dishonesty is a widespread problem in colleges in many countries, and it is getting worse. One particular form of cheating has become especially common in the age of the internet: students buying custom-written essays–a.k.a. “contract cheating.” A recent study estimated that over 15% of college students had paid someone else to do their work for them; A while ago findingtimetowrite wrote a

A while ago findingtimetowrite wrote a