by Elizabeth S. Bernstein

Feminists are often accused of downgrading motherhood. The accusation is ridiculous: motherhood hit rock bottom long before the new feminist wave broke. —Germaine Greer (1984) 1

What sort of picture does the phrase “stay-at-home mother” call to mind? Searching images and stock photos online, you may find a reasonably diverse looking group of contemporary women with young children. There are, after all, millions of mothers at home in the United States today – over a third of those with children under the age of six – and they are a demographically diverse lot.

But there is also a particular variant of the photos on offer which tends to be favored by editors looking for illustrations of at-home mothering. It is the image of that iconic housewife of the 1950s, in her apron and heels. The woman who, these many decades later, is still our foil. The woman whose fate we were saved from by second-wave feminism.

This woman, the story goes, had been influenced by men to devote herself to her children to an excessive degree. The very essence of the “feminine mystique” Betty Friedan decried was that it urged postwar wives to find their fulfillment in “sexual passivity, acceptance of male domination, and nurturing motherhood.” 2 Read more »

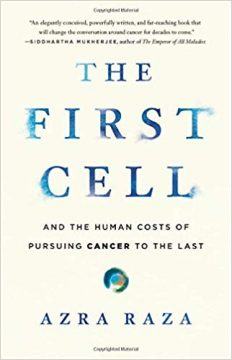

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given.

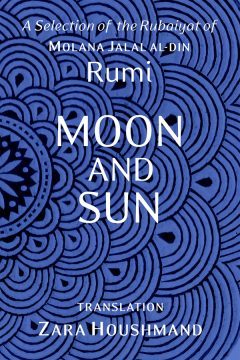

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given. These energetic lines open Moon and Sun: Rumi’s Rubaiyat, Zara Houshmand’s brilliant translation of selected ruba’iyat – quatrains – by Molana Jalaluddin Rumi, and set the tone for an inspiring and exhilarating sojourn through the passions of the peerless Sage of Konya.

These energetic lines open Moon and Sun: Rumi’s Rubaiyat, Zara Houshmand’s brilliant translation of selected ruba’iyat – quatrains – by Molana Jalaluddin Rumi, and set the tone for an inspiring and exhilarating sojourn through the passions of the peerless Sage of Konya. Sutcliffe views the concept of “disdain” as central to Scarlatti’s approach: the term, first applied to the composer by Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli, connotes a deliberate rejection of convention. Scarlatti is well-versed in, but does not fully adopt, the conventions of the

Sutcliffe views the concept of “disdain” as central to Scarlatti’s approach: the term, first applied to the composer by Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli, connotes a deliberate rejection of convention. Scarlatti is well-versed in, but does not fully adopt, the conventions of the

One autumn I’m suddenly taller than my mother. The euphoria of wearing her heels and blouses will, for an instant, distract me from the loss of inhabiting the innocence of a child’s body—the hundred scents and stains of tumbling on grass, the anthills and hot powdery breath of brick-walls climbed, the textures of twigs and nodes of branches and wet doll hair and rubber bands, kite paper and tamarind-candy wrappers, the cicada-like sound of pencil sharpeners, the popping of coca cola bottle caps, of cracking pine nuts in the long winter evenings— will blunt and vanish, one by one.

One autumn I’m suddenly taller than my mother. The euphoria of wearing her heels and blouses will, for an instant, distract me from the loss of inhabiting the innocence of a child’s body—the hundred scents and stains of tumbling on grass, the anthills and hot powdery breath of brick-walls climbed, the textures of twigs and nodes of branches and wet doll hair and rubber bands, kite paper and tamarind-candy wrappers, the cicada-like sound of pencil sharpeners, the popping of coca cola bottle caps, of cracking pine nuts in the long winter evenings— will blunt and vanish, one by one.

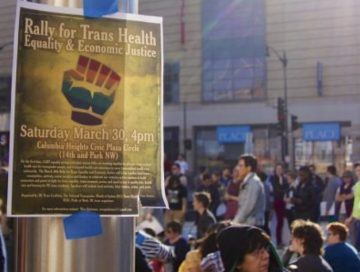

We are all in some sense equal. Aren’t we? The Declaration of American Independence says that, “We hold these Truths [with a capital ‘T’!] to be self-evident” – number one being “that all Men are created equal.” Immediately, you probably want to amend that. Maybe, not “created”, and surely not only “Men” – and, of course, there’s the painful irony of a group of landed-gentry proclaiming the equality of all men, while also holding (at that point) over 300,000 slaves. But don’t we still believe, all that aside, that all people are, in some sense, equal? Isn’t this a central and orienting principle of our social and political world? What should we say, then, about what equality is for us now?

We are all in some sense equal. Aren’t we? The Declaration of American Independence says that, “We hold these Truths [with a capital ‘T’!] to be self-evident” – number one being “that all Men are created equal.” Immediately, you probably want to amend that. Maybe, not “created”, and surely not only “Men” – and, of course, there’s the painful irony of a group of landed-gentry proclaiming the equality of all men, while also holding (at that point) over 300,000 slaves. But don’t we still believe, all that aside, that all people are, in some sense, equal? Isn’t this a central and orienting principle of our social and political world? What should we say, then, about what equality is for us now? Einstein had called nationalism ‘an infantile disease, the measles of mankind’. Many contemporary cosmopolitan liberals are similarly skeptical, contemptuous or dismissive, as its current epidemic rages all around the world particularly in the form of right-wing extremist or populist movements. While I understand the liberal attitude, I think it’ll be irresponsible of us to let the illiberals meanwhile hijack the idea of nationalism for their nefarious purpose. Nationalism is too passionate and historically explosive an issue to be left to their tender mercies. It is important to fight the virulent forms of the disease with an appropriate antidote and try to vaccinate as many as possible particularly in the younger generations.

Einstein had called nationalism ‘an infantile disease, the measles of mankind’. Many contemporary cosmopolitan liberals are similarly skeptical, contemptuous or dismissive, as its current epidemic rages all around the world particularly in the form of right-wing extremist or populist movements. While I understand the liberal attitude, I think it’ll be irresponsible of us to let the illiberals meanwhile hijack the idea of nationalism for their nefarious purpose. Nationalism is too passionate and historically explosive an issue to be left to their tender mercies. It is important to fight the virulent forms of the disease with an appropriate antidote and try to vaccinate as many as possible particularly in the younger generations.