by Katie Poore

A few weeks ago, I journeyed up to Chamonix-Mont-Blanc during a work vacation. I went with a few friends of mine, embarking from our homes in Chambéry, France, taking a train to Annecy, and a bus to our final destination. I was outrageously tired, having stayed up until some ungodly hour of the morning playing, of all things, Just Dance.

After shuffling around Annecy for a few hours, laden down with luggage and waiting for the arrival of our bus, we were on our way into the so-called heart of the French Alps. As badly as I wanted to sleep, I couldn’t tear my eyes away from the changing landscape, framed through immense bus windows. I pressed my forehead against the glass and turned on some music, hoping to block out any sounds of more mundane humanity for just a moment. Views like this always felt too sacred for human chatter, for the faint rumble of an engine. I couldn’t do much about the vibrating of the bus, or the fact that I was on a bus at all, but this I needed: a world composed of only those things which have taken great thought and time.

For me, this was those mountains and Gregory Alan Isakov, a singer-songwriter and farmer based near Boulder, Colorado, who writes his songs in a barn-studio plastered with giant pieces of paper scrawled with potential song lyrics. He calls songwriting “laborious” in an interview with Atwood Magazine, but this labor gives way to music that is something else entirely: quietly transcendent, aching, longing, at once fragile and formidable. It feels clear that these songs are constructed slowly, scrupulously, mined from the depths of feeling. Anyone familiar with that so-often agonizing creative process might feel the erasures and changes, the takes and retakes, the immense and fatiguing degree of ceaseless thought and emotion that slowly amalgamates to form each of his compositions.

It felt like the only proper music to which I might listen: carefully composed and somehow soaring, a perfect sonic accompaniment to the mountains whose formations might well be described the same way. Read more »

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

I was always a skinny fuck. Forever the thinnest kid in the class, and for a longtime the second shortest boy (thank you, David Mehler). My stick-figure proportions were the thing of legend. I could suck my stomach in so far that some people swore they could touch the inside of my spine. My uncle used to refer to me as the Biafra Boy, a tasteless reference to the gruesome famine that accompanied the Nigerian Civil War (1967 – 70). In an effort to fatten me up, my grandmother would serve me breakfast cereal with half-and-half instead of milk. It was to no avail. A growth spurt in the 8th grade got me well above the short kids, but my body didn’t fill out. I graduated high school standing five feet, nine and a half inches tall, and weighing less than 120 pounds.

I was always a skinny fuck. Forever the thinnest kid in the class, and for a longtime the second shortest boy (thank you, David Mehler). My stick-figure proportions were the thing of legend. I could suck my stomach in so far that some people swore they could touch the inside of my spine. My uncle used to refer to me as the Biafra Boy, a tasteless reference to the gruesome famine that accompanied the Nigerian Civil War (1967 – 70). In an effort to fatten me up, my grandmother would serve me breakfast cereal with half-and-half instead of milk. It was to no avail. A growth spurt in the 8th grade got me well above the short kids, but my body didn’t fill out. I graduated high school standing five feet, nine and a half inches tall, and weighing less than 120 pounds. Economics. The dismal science. All those numbers and graphs, formulas and derivations, tombstone-sized copies of Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus’s Macroeconomics (now apparently in its 19th edition), and memories of the detritus that came with them: half-filled coffee cups and overfilled ashtrays, mechanical pencils and HP-45s.

Economics. The dismal science. All those numbers and graphs, formulas and derivations, tombstone-sized copies of Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus’s Macroeconomics (now apparently in its 19th edition), and memories of the detritus that came with them: half-filled coffee cups and overfilled ashtrays, mechanical pencils and HP-45s.

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the  The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

“I don’t like Polish people,” he says, and raises an eyebrow suggesting “How could anybody, really?”

“I don’t like Polish people,” he says, and raises an eyebrow suggesting “How could anybody, really?”  are suitable to it. The computer is ontologically ambiguous. Can it think, or only calculate? Is it a brain or only a machine?

are suitable to it. The computer is ontologically ambiguous. Can it think, or only calculate? Is it a brain or only a machine?

Last year we drove across the country. We had one cassette tape to listen to on the entire trip. I don’t remember what it was. —Steven Wright

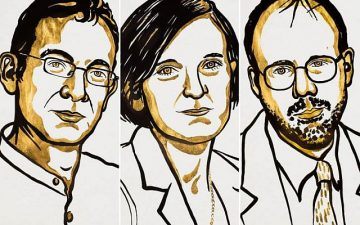

Last year we drove across the country. We had one cassette tape to listen to on the entire trip. I don’t remember what it was. —Steven Wright As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).