by Bill Murray

Americans stood as implacable enemies of National Socialism. As an American myself, on the anniversary of the Berlin Wall’s fall, I want to tell you about my dear friend the Nazi soldier.

“I don’t like Polish people,” he says, and raises an eyebrow suggesting “How could anybody, really?”

“I don’t like Polish people,” he says, and raises an eyebrow suggesting “How could anybody, really?”

Among other things, it’s common knowledge their language is incomprehensible.

At 90, he has earned his opinions.

He’s gray and a little severe, turned out today in a light spring jacket, tan sweater and shirt with matching scarf. He takes small steps, pitched forward just a little. He’s tall, thin, bright and upright, and he walks us up and down the streets of Wittenberg all day long.

We suggested a visit and he’s determined we make the day of it. We’ve come all this way, haven’t we?

His father was born in Poland, but mind you, Poland’s borders waved like a battle flag. When his father was born Posen was German. Today it is Poznan, in Poland.

His father fought the Great War riding great horses for the Kaiser, a dragooneer fighting hand to hand with lances. Imagine. His father owed oaths to three sovereigns in his lifetime: Kaiser Wilhelm, the Weimar government and the Third Reich. Imagine that, too.

Erich was born in 1929.

His mother never dreamed he’d go to war. At the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria in 1938, and during the occupation of the Sudetenland later that year, she’d never have conjured the prospects of her Grundschuler son marching off to war. When Germany invaded Poland to start the war in earnest, she thanked the heavens her boy wasn’t even ten.

But in time her boy was fifteen and the Reich wheezed for fighting stock. He got six weeks training – rifles, hand grenades, knives. They marched his cadre off to dig anti-tank trenches near Bratislava on the pretense they were to learn advanced farming techniques to feed the Vaterland. Military leaders from the Reich flew in to laud their progress. In the end his unit marched for two desperate days trying but failing to surrender to the Americans.

•••••

Early on the morning of 2 May, 1944 Russian soldiers captured the Reich Chancellery. Fighting continued scattershot in the hinterland, but after a week the Red Army had collected German remnants, sorry unfledged youth like Erich and their press-ganged elders into a stadium in Prague.

They ran them through a gauntlet of sticks and pipes. They held them rain or shine, no shelter, no change of clothes, for a week gave them only bread, then marched the lot to Germany.

Erich feels the Russians were fair enough. They didn’t break bones. His schoolgirl future wife, who hid at that moment in unmitigated terror with her mother and her bicycle in a Berlin basement, would see things differently.

Ordinary Czech people, though, they were rough. Erich’s rag-tag column of spent pensioners and boy soldiers came to further woe. In the villages they beat them with sticks and bats and the Russians did nothing to stop them. The prisoners’ tongues were so dry they filled their mouths.

They came to a camp at Dresden, a German POW camp for Russians that once held 3000. The Russians used it for 18,000 Germans. He was there a month. Sleeping, when one man turned over, the next three or four had to, too.

Finally freed with no food, aid or resources, he found his way to Berlin, a boy of sixteen, a war veteran. He had no idea if his parents were alive. His father had been a fireman. Because of the bombing, during the war he worked day and night. It was a dangerous job.

Tremulously, Erich walked up to his old house, knocked, and his mother answered. She peered into his eyes and dismissed him: “I already gave food to soldiers,” before at last she recognized her son.

He mimics her, putting his palms to his cheeks and exclaiming, “My boy!”

He was so gaunt she didn’t recognize her own son.

His family was reunited but their city lay in ruins. He and his father bicycled 100 kilometers, deep into the Spreewald to trade with farmers, for there was no food in Berlin. 100 kilometers on a bike, for food.

One time it was a Sunday. He was due in school the next day, learning Latin and mathematics but when they got home he leaned his bicycle against the wall and slept all the way through until noon on Tuesday.

They traded nails, tools, and especially soap for food. His father could get soap. Firemen had a police connection; they were the Fire Police. Maybe that had something to do with it, but he was never clear, he was just sixteen.

What food could you get from farmers after the war? It depended on how many nails you brought, how much soap. But the staple was corn.

•••••

Erich came to love a woman, and when they wed in 1951 they had nothing. Basic weddings were free because of the church tax, but the pastor would suggest every extra you might imagine, a tree and flowers and cards and silly things, but they had nothing and told the man they wanted it simple.

Together they finished school as lawyers. Inge became a family court judge. Erich became a criminal attorney. By happenstance they lived in western Berlin.

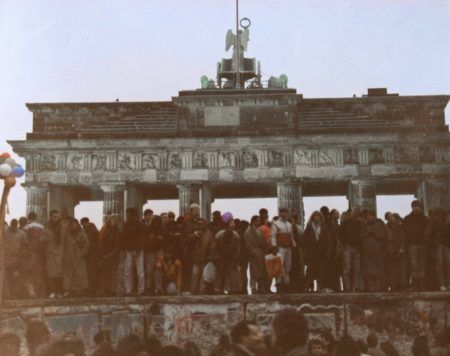

I flew into Berlin to stand atop the wall on New Year’s Eve 1989, a privileged tourist, and flew out. Once the wall went up Erich and Inge had no such freedom of movement, hemmed in by East Germany for nearly three decades, denied the opportunity to venture far out into the countryside around town. Still, that was so much better than living on the other side.

They had a wooden boat for fifty years. They would pack enough food for the weekend and live on the boat from Friday night until Monday morning to get out of town. It gave them a measure of freedom. Except they had to be careful. There were buoys beyond which if they drifted in error, they were liable to be shot. Others were.

Sometime in the 2000s they sailed us over to the Gleineke bridge, the famous spy bridge where Francis Gary Powers and other prisoners were swapped between the East and West Blocs, and pointed to enticing woodlands on the other side that they’d been able to see but not visit.

•••••

Inge and her mother lived in Berlin right through the allies’ assault, until the block of flats where they lived was bombed and burned. They found shelter in the neighborhood, sharing bedrooms with others and moved around from time to time before the German surrender, when they hid from the Russians.

They so wanted the Americans to arrive first because of the stories they’d heard of Russian soldiers and rape. There was a public shelter across the street from the last place they lived, nearby enough that Inge, a teenager in 1945, and her mother watched in terror as Russian soldiers went in and women came out, ‘blouses ripped’ and hysterical.

Finally one day a single Russian soldier, very young, she said, pounded on their door and opened it to find her and her mother inside. “This is it,” her mother said, the moment of horror they’d conjured in their minds in all those nights underground, burrowing like rodents against the bombs and the fires.

But the soldier just looked, then closed the door.

Later a Russian soldier stole her bicycle, but he left them alone.

•••••

She thought that because of some translation problem, when the Russians asked the Germans what kind of seed they wanted to plant they misunderstood that the Germans wanted corn instead of wheat, so now there are corn fields where there weren’t before. Which her future husband bicycled into the Spreewald for, instead of starving.

People ate most of the kernels the Russians brought instead of planting them. Which is part of the reason she loved the Americans. They brought actual bread instead of seeds. She said she would never forget when she and her mother got a whole loaf of bread from the Americans.

When President Kennedy came to give his ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’ speech, of course she went, but to Inge, more than Kennedy the star of the show was General Lucius Clay, the head of the American sektor, who came out of retirement to accompany Kennedy. She said Berliners felt it was he who had fed and saved them.

•••••

They traveled widely once they could, after the wall came down. They visited all the European capitals. They survived a vicious hurricane in St. Maarten. They liked the warmth of the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf in winter and spent lots of beach time in Cyprus and Doha and Dubai. We met some twenty-five years ago in their wild, liberated traveling days, on a beach in Polynesia.

•••••

American World War II veterans’ numbers are dropping by about 350 a day. They are dying in Berlin too.

America’s dwindling Great War veterans have led remarkable lives. So too have the remaining veterans in Berlin, the surviving ones just boys at the time, conscripted and forced toward a desperate fight, vanquished and left in a city in ruins, a city then rent asunder for 28 years more, divided east from west and friend from friend by the Berlin Wall.

In April 2014 Inge, the family court judge and wife of the young soldier Erich, died in Berlin. Erich lives on in Wilmersdorf. His 90th birthday was three months ago.

•••••

For a short look at Germany’s last thirty years see Constanze Stelzenmüller’s essay German Lessons: Thirty years after the end of history: Elements of an education.

For the fall of the wall see The Collapse: The Accidental Opening of the Berlin Wall by Mary Elise Sarotte and the newly released Checkpoint Charlie: The Cold War, The Berlin Wall, and the Most Dangerous Place On Earth by Iain MacGregor.