by R. Passov

The British Boxing Board of Control (BBBofC) provides a short history of boxing. It’s an ancient sport. The Romans fought each other wearing cestus, sometimes to the death. Before them so the Greeks. In the fourth century AD, tired of the violence, the Romans outlaw the sport.

According to the BBBofC, fourteen hundred years pass before boxing re-appears in London as an organized sport for bettors. In 1719, a James Figg is recognized as the First Heavyweight Champion. His protégé, John Broughton introduces rules. A century later, John Graham fighting for the 8th Marquis of Queensberry, codifies the rules as the Queensberry Rules, which still govern the sport:

A boxer shall wear gloves. Wrestling is not allowed. The match is no longer a fight to the finish. Rounds shall last for three minutes. A boxer must rise before a 10 second count and the match shall be fought in a standardized ring – more or less.

Queensberry Rules also include – No shoes or boots with springs and a man hanging off the ropes with his toes off the ground shall be considered down.

* * *

George Foreman, in Spike Jones’s magnificent documentary Facing Ali says that Muhammad Ali was at his very best against Cleveland Big Cat Williams. In that same documentary George Chuvalo, the former Canadian Heavy weight champion, says otherwise.

In the first of his two fights against Ali, Chuvalo was a fill-in. Ali had announced his decision to join the Nation of Islam. His handlers thought Toronto would be far enough from the backlash to face Ernie Terrell, a tall, talented, mafia-controlled fighter. Terrell’s handlers, bowing to pressure from the United States, backed out. Chuvalo, a hard-partying twenty-four-year-old, had just seventeen days to stop drinking and start training.

In a match held in Ali’s home town, Louisville, Ky., Chuvalo had faced Mike DeJohn. Ali sat ringside as Chuvalo got a boxing lesson. In the second round, DeJohn, knocked down twice, was kept from a third fall by the ropes where he lay, back bent into a bow, fully unconscious. Instead of ruling another knockdown and awarding the match to Chuvalo, the referee stopped action for over a minute while he conferred with DeJohn’s corner.

Reaching into the rule books it was decided that Chuvalo had wrestled DeJohn, a clear violation of Queensberry rules. DeJohn regained his senses. In the sixth round, after his second knockdown, he’s helped to his feet by the referee. Somehow Chuvalo managed to win by decision. Asked for a comment after the fight he offered, “I thought the referee was DeJohn’s brother.”

Ali, watching ringside, noted that Chuvalo “… fights like a washer-woman, no style.” Not to be outdone, Chuvalo showed up to the ceremonial contract-signing with Ali wearing a country-girl dress, under a white wig, dragging a mop and bucket.

Inside the ring, Chuvalo proved himself. Ali won by decision in what he would come to say was his toughest fight.

Foreman, after decimating the heavyweight ranks, faced a twice-defeated Ali near the end of his career. On a steamy morning in the capital of a country then known as Zaire, for seven rounds, Ali lay against the ropes as a powerful, overconfident young fighter punched past his stamina.

In the eighth round Ali came off the ropes, hit Foreman high on the temple then watched him fall.

* * *

Paraphrasing from Wikipedia:

Cleveland was born in Griffin GA on June 30th, 1933 and passed away in Houston on September 3rd, 1999.

His path to the heavyweight championship was twice blocked by losses to Sonny Liston, a widely feared, also mafia-controlled fighter who, after two consecutive losses to Ali, retired to a short life of heroin.

On November 29th, 1964 Cleveland would have the misfortune of getting shot.

Dale Witten, a Highway Patrolman, stopped a car on the outskirts of Houston. Cleveland was driving. During an altercation that has never been explained, Witten shot Cleveland at close range. The bullet, fired from a .357 Magnum, passed through small intestines before lodging in Cleveland’s right hip.

Across four surgeries, Cleveland lost 60 pounds but not the bullet. After regaining his strength, pleading no contest and paying a $50 fine, he was briefly incarcerated.

Almost two years later, in a match against Ali, Cleveland would get his last chance at the Heavyweight title. On the night of the fight, Dale Witten visited his dressing room to wish him good luck.

The Big Cat weighed in at 210 lb. to Ali’s 212 ½. Both were listed at 6’ 3”.

On YouTube you can hear the pre-fight announcer commenting, “Excellent close up of the Champion.”

As the fighters circle Ali slides his feet on the mat, moving one forward, the other backwards, giving the effect of a cartoon character getting ready to let loose – the Ali shuffle. His 7th title defense in just two years, by today’s standards, Ali was a busy champion.

“Everyone has tried to get him caught on the ropes,” a commentator notes. Ten years later, Ali would “rope a dope” Foreman.

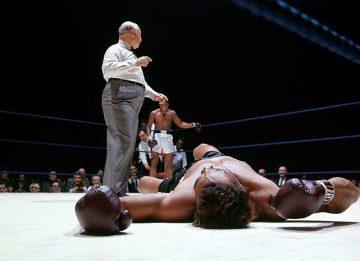

You can see in the film that though Big Cat is sculptured, beautiful, powerful, something is missing. His right foot drags. Hands high for protection, elbows in, there’s no side-to-side. Just a straight-up target that Ali hits over and over. The fight is over after three rounds. Big Cat fails to land a single punch.

* * *

The referee, Henry Kessler, is barely in the frame. When Big Cat goes down – three times in the second round – Kessler bends over his pot belly, rhythmically swinging his arms back and forth to the count. Each time Big Cat finds his feet Kessler, without asking the customary “are you ok?” turns him back toward Ali.

The part owner of three steel companies, Kessler was a jaunty fellow who flew over 200,000 miles per year, “… appearing in the city of the fight without knowing which of the bouts on the card he’d referee or whether he’d be called at all.”

All that traveling for $50 to $100 of “mad money” that he gave to charity.

In a NewYorker profile, Kessler shared thoughts on his hobby:

“A referee is supposed to be incorporeal. When I push fighters apart, I give each the same amount of pressure. But generally I try to talk them out of clinching: ‘Stop clinching, John.’ If one fighter is stuck in a corner and he’s trying desperately to hold, I say, ‘Fight your way out of it, John.’

“I don’t break semi-clinches, because infighting is the forte of many good boxers and it’s a gaffe to penalize somebody for it … When a fighter butts, hits with the heel of his glove, or gouges, I say, ‘Look, John, you’re not listening to me.’ I always have a smile for the fighters…

Kessler wore bow ties and advised his refereeing colleagues to do the same, believing that it “…lends éclat.” Once, after watching him receive the full force of a fighter’s errant punch, a crowd “…giggled for fifteen minutes. They felt it was a sort of lagniappe.”

* * *

Ali fought twice more before all fifty states, citing his refusal to serve in the army, revoke his boxing license. Three years pass before the ban cracks. In 1970, Atlanta offers a license. Ali dispenses hard-hitting Jerry Quarry in three rounds. Then New York where Oscar Bonavena, a tough Argentinian exposes a diminished Ali. The fight wasn’t stopped until the fifteenth round.

Ali’s next fight is against Smokin’ Joe Frazier – the Fight of the Century. Frazier holds the title Ali had been forced to vacate. They meet in the newly built Madison Square Garden. Dale Witten patrols the outskirts of Houston. Henry Kessler is a witness, alongside Frank Sinatra, Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, Woody Allen and the rest of New York’s glitterati.

In the lead up to the fight, Ali tries to brand Frazier an Uncle Tom. An insulted Frazier would “fight mad,” lose his composure and as the fight progressed, wear down.

One of nine children, Frazier was raised on a subsistence farm in Beaufort, South Carolina. After speaking his mind to a white farmer who had beaten a boy, Frazier’s mother offered some advice: “If you can’t get along with white folk you’d better move on.” Frazier got on a bus and landed in New York City, all of fifteen years old. Three years later he was training in a gym in Philadelphia and on his way to the 1964 Olympics.

In Facing Ali, Ron Lyle, who while serving time for manslaughter kept himself in shape by doing 1000 pushups in under an hour, praised Frazier’s boxing skills. Then he added, “What Ali did was wrong. Frazier was blacker than Ali.”

Ali understood the media in a way familiar to today’s Twitter-Facebook generation. And as happens so often today, something pushed him past a threshold. Perhaps the fear that any fighter has of his opponent got the better of him.

Frazier knew his purchase was as hard-won as any man’s. He also knew who was watching, saw in the audience the Dale Whittens and the New York celebrities. Saw how little was the change for two black men. The effect of Ali’s branding, according to George Forman, was to make Frazier prefer death over losing.

In Spike Jones’s documentary, under slurred speech made clear by subtitles, Frazier cries. If it was just a fight, maybe Ali could have won. But why did he do that? Frazier asks. Why did he call me an Uncle Tom.

Frazier had one weakness. His bent-forward style exposed him to an uppercut which Foreman would use to send him to the canvass six times in two rounds. But Ali had one glaring deficiency. An effective uppercut, launched at close range, pulling power from the hips, requires planted feet.

Late in the fifteenth round of a tight fight, Ali went down.

* * *

In 1974, when Ali came off the ropes to knockout George Foreman, many thought he was at his greatest. They too were wrong.

In the Spike Jones video, all of Ali’s then living opponents have their chance to speak freely and all but one – Ernie Terrell who, when he got his shot at Ali, also got gloved in the eye – speak of how Ali did not need to seek them out. Did not need to give them their shot into which they put their all.

In his final years, bereft of the power of his voice, there was no bitterness, only love and understanding. In that silence, willing a smile, Ali achieved the full measure of his greatness.