by Ali Minai

For the last three years, I have struggled with a dilemma: As a reasonable, quite liberal person, what should I think of my 60 million fellow Americans who voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and the vast majority of whom continue to support him today? Normally, a personal dilemma is a private thing, not a topic for public airing, but I feel that this particular problem is one the vexes many others – perhaps even a majority of Americans, as more of us voted for Hillary Clinton and many did not vote at all. Since that bleak day in November 2016, an unspoken – and sometimes loudly spoken – question hangs in the air: What kind of “deplorable” person would vote for Donald Trump?

For the last three years, I have struggled with a dilemma: As a reasonable, quite liberal person, what should I think of my 60 million fellow Americans who voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and the vast majority of whom continue to support him today? Normally, a personal dilemma is a private thing, not a topic for public airing, but I feel that this particular problem is one the vexes many others – perhaps even a majority of Americans, as more of us voted for Hillary Clinton and many did not vote at all. Since that bleak day in November 2016, an unspoken – and sometimes loudly spoken – question hangs in the air: What kind of “deplorable” person would vote for Donald Trump?

By now, it is clear to any reasonably sentient person that Donald Trump is a venal, corrupt, narcissistic individual with no shred of human decency or moral principle. From his first announcement where he called Mexicans rapists and criminals, to the Access Hollywood tape exposing his habit of groping women, the mocking of a disabled journalist, the xenophobic Muslim ban, calling white supremacists “very fine people”, the abduction and caging of innocent children, the destruction of environmental protections, the denial of the climate threat, the shredding of all ethical norms, the open defiance of laws, the appointment of racists and thugs to high office, the pardoning of war criminals, the decimation of government institutions and policies, the betrayal of allies, the subversion of American democracy, the celebration of despots, and blind obedience to Vladimir Putin – and much, much more – everything Trump has done has established him as a person of truly monumental vice. And yet, something like 40% of American voters still support him reliably, including many who have been grievously hurt by his policies and know that they have been hurt. Why? And how should those who cannot stand Trump relate to them? Read more »

In November 1918, a 17-year-student from Rome sat for the entrance examination of the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy’s most prestigious science institution. Students applying to the institute had to write an essay on a topic that the examiners picked. The topics were usually quite general, so the students had considerable leeway. Most students wrote about well-known subjects that they had already learnt about in high school. But this student was different. The title of the topic he had been given was “Characteristics of Sound”, and instead of stating basic facts about sound, he “set forth the partial differential equation of a vibrating rod and solved it using Fourier analysis, finding the eigenvalues and eigenfrequencies. The entire essay continued on this level which would have been creditable for a doctoral examination.” The man writing these words was the 17-year-old’s future student, friend and Nobel laureate, Emilio Segre. The student was Enrico Fermi. The examiner was so startled by the originality and sophistication of Fermi’s analysis that he broke precedent and invited the boy to meet him in his office, partly to make sure that the essay had not been plagiarized. After convincing himself that Enrico had done the work himself, the examiner congratulated him and predicted that he would become an important scientist.

In November 1918, a 17-year-student from Rome sat for the entrance examination of the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy’s most prestigious science institution. Students applying to the institute had to write an essay on a topic that the examiners picked. The topics were usually quite general, so the students had considerable leeway. Most students wrote about well-known subjects that they had already learnt about in high school. But this student was different. The title of the topic he had been given was “Characteristics of Sound”, and instead of stating basic facts about sound, he “set forth the partial differential equation of a vibrating rod and solved it using Fourier analysis, finding the eigenvalues and eigenfrequencies. The entire essay continued on this level which would have been creditable for a doctoral examination.” The man writing these words was the 17-year-old’s future student, friend and Nobel laureate, Emilio Segre. The student was Enrico Fermi. The examiner was so startled by the originality and sophistication of Fermi’s analysis that he broke precedent and invited the boy to meet him in his office, partly to make sure that the essay had not been plagiarized. After convincing himself that Enrico had done the work himself, the examiner congratulated him and predicted that he would become an important scientist.

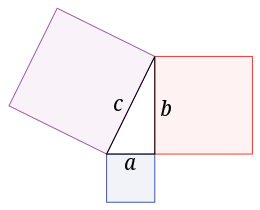

I have some very simple New Year’s resolutions, and some that require an entire column to spell out. One example of the latter is that I want to make a subtle but meaningful change in how I talk to my (middle and high school) math students about proofs.

I have some very simple New Year’s resolutions, and some that require an entire column to spell out. One example of the latter is that I want to make a subtle but meaningful change in how I talk to my (middle and high school) math students about proofs.

We find ourselves always in the middle of an experience. But it’s what we do next – how we characterize the experience – that lays down a host of important and almost subterranean conditions. Am I sitting in a chair, gazing out the dusty window into a world of sunlight, trees, and snow? Am I meditating on the nature of experience? Am I praying? Am I simply spacing out? Depending on which way I parse whatever the hell I’m up to, my experience shifts from something ineffable (or at any rate, not currently effed) to something meaningful and determinate, festooned with many other conversational hooks and openings: “enjoying nature”, “introspecting”, “conversing with God”, “resting”, “procrastinating”, and so on. Putting the experience into words tells me what to do with it next.

We find ourselves always in the middle of an experience. But it’s what we do next – how we characterize the experience – that lays down a host of important and almost subterranean conditions. Am I sitting in a chair, gazing out the dusty window into a world of sunlight, trees, and snow? Am I meditating on the nature of experience? Am I praying? Am I simply spacing out? Depending on which way I parse whatever the hell I’m up to, my experience shifts from something ineffable (or at any rate, not currently effed) to something meaningful and determinate, festooned with many other conversational hooks and openings: “enjoying nature”, “introspecting”, “conversing with God”, “resting”, “procrastinating”, and so on. Putting the experience into words tells me what to do with it next.

Forever is a long time.

Forever is a long time.

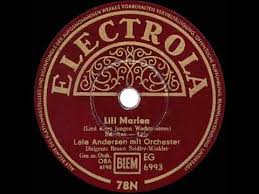

Lili Marleen is one of the best known songs of the twentieth century. A plaintive expression of a soldier’s desire to be with his girlfriend, it is indelibly associated with World War II, in part because it was popular with soldiers on both sides. It was

Lili Marleen is one of the best known songs of the twentieth century. A plaintive expression of a soldier’s desire to be with his girlfriend, it is indelibly associated with World War II, in part because it was popular with soldiers on both sides. It was  Marlene Dietrich, who worked tirelessly during world war two entertaining allied troops, also recorded both a

Marlene Dietrich, who worked tirelessly during world war two entertaining allied troops, also recorded both a

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.