by Steve Gardner

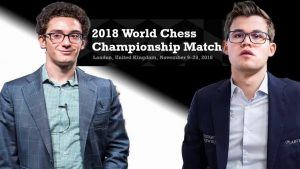

Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana faced off for the World Chess Championship over three weeks London. I’d been looking forward to the match all year, and following the progress of the two players towards it. This piece looks at the two players and the situation before the match, gives an account of the Championship games, and concludes with some reflections on the significance of the match for the participants, and for the sport.

Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana faced off for the World Chess Championship over three weeks London. I’d been looking forward to the match all year, and following the progress of the two players towards it. This piece looks at the two players and the situation before the match, gives an account of the Championship games, and concludes with some reflections on the significance of the match for the participants, and for the sport.

Before the Match

The Challenger – Fabiano Caruana

Caruana is the toughest test Carlsen has yet faced in a World Championship match: more creative and dangerous in attack than the stolid defensive master Sergey Karjakin, and younger and more formidable even than the great Vishy Anand, who, while he was one the greatest players of his generation, was well into his forties and past the peak of his playing strength in the two world championship matches he played against Carlsen in 2013 and 2014. Caruana had a poor start to the year at the Tata Steel tournament in Wijk aan Zee in January, but since then he has been in utterly brilliant form, winning not only the Candidates tournament in March to earn his right to play this match, but also the Grenke Chess Classic in April, the Norway Chess tournament in June, and (jointly with Carlsen and Aronian), the Sinquefield Cup in August. He also finished second in the US Championship. This sustained run of strong chess has seen his rating rise from 2799 at the end of 2017 to 2832, within 3 points of Carlsen, a statistical near-tie; this is the first time since Carlsen’s rise to the top of the chess rankings in 2012 that any player has been so close to him in rating. A single victory by Caruana during the match would see him overtake Carlsen and become the #1-ranked player in the world.

The Champion – Magnus Carlsen

Carlsen’s form in 2018 was slightly less impressive, though by no means bad. He won the Tata Steel tournament in January, the Fischer Random World Championship in February (defeating Hikaru Nakamura), the Shamkir Chess tournament in April, and as mentioned above shared first place in the Sinquefield Cup in August. He’s played many beautiful games in his characteristic boa constrictor style, squeezing out wins in long games out of technical endgame positions, including a memorable victory over Nakamura in the last round of the Sinquefield Cup, demonstrating a beautiful winning idea. But this year we have also seen some cracks appear in his normally impregnable composure, an un-Magnus-like indecisiveness at key moments, opponents allowed to escape lost positions, such as his game with Caruana at the Sinquefield Cup where Magnus misplayed a winning attack and Caruana escaped with a draw. His rating going into the match of 2835 had scarcely changed this year; if it hadn’t risen like Caruana’s, just maintaining a rating at these stratospheric heights is an impressive achievement. Still, Carlsen’s peak rating of 2882 (the highest ever by any human player) was achieved in May 2014, and is nearly 50 points higher than his rating now. So questions were in the air which the course of the match would amplify: what are the reasons for Carlsen’s rating decline? Would he be able to bring his best game to the match? And if not, would that be enough to keep Caruana at bay?

The Battle in Prospect

The match offered an intriguing and compelling contrast of styles. Caruana is a natural attacker, at home in tactical complications. Trained by Rustam Kasimdzhanov, he is deeply prepared in opening theory, as he showed with a pair of wins with black in the Petroff Defence, both in the final rounds of the Candidates and Grenke tournaments, and both to secure tournament victories. He’s a player in the line of Garry Kasparov, who also started as an attacker and developed from there into a universal player with a profound knowledge of openings.

Carlsen, famously, is cast from a different mould, more like Capablanca or Karpov. His strength is not in openings; there is no Carlsen Variation or Carlsen Gambit named for him. Rather than seek an advantage from the opening, he aims to steer the game away from deeply analysed lines into modest positions with almost imperceptible advantages of space or piece activity or control of key squares, where he can outplay his opponent in the middle and endgames. Such positions, being modest, are much easier to find out of the opening than sharp and complicated ones – Carlsen can and does play just about anything out of the opening. His genius, probably unequalled in chess history, lies in his near-magical ability to convert these microscopic advantages into winning positions. One of the key battles in the match would be whether Caruana could somehow lead Carlsen along prepared paths. Carlsen, having more paths to choose from, had the easier task here and therefore perhaps the opening advantage.

If you looked just at their head-to-head record in classical games – where Carlsen led 10-5 with 18 draws – you might have predicted a relatively easy win for the World Champion. But this match was probably the most difficult World Championship match to predict since the Kramnik – Anand match of 2008, and perhaps since the second Karpov – Kasparov match of 1985. There’s not now any appreciable difference between them in ability. There is great respect between them, but no fear: both knew that they were capable of winning – and of losing. And even if there were a difference in strength between them, the shortness of the match – just 12 games – would increase the likelihood of the weaker player pulling off an upset. But prior to the match, I think two factors gave Carlsen a slight edge: firstly, his greater experience in world championship matches, which present unusual psychological challenges for which I thought Carlsen would be better prepared, and secondly, the tie-break rules, which say that if the score is 6-6 after 12 games, the match would be decided by a series of rapid games, and if needed, blitz games. Carlsen is supreme at these shorter time controls. In a short match between two such evenly-matched players, a 6-6 scoreline was a strong possibility. The only surprising result would be an easy victory for either player.

The games

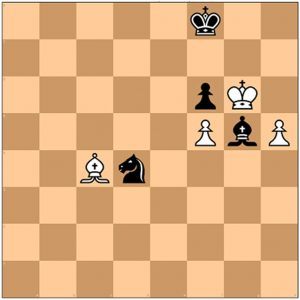

Opening games of World Championship matches are often tentative affairs, with both players trying to settle their nerves, feel each other out, and get through the game without making any mistakes. Game 1 of this match ran sensationally against type, producing a tense and epic game. Caruana had the White pieces and opened, as expected, with 1.e4. Carlsen normally plays 1…e5 here and one could expect a Spanish (2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5) or perhaps a Scotch (2.d4) game. But straight away, Carlsen surprised his opponent by playing the Sicilian 1…c5, and after 2.Nf3 Nc6 Caruana opted for a Rossolimo with 3.Bb5. Perhaps Caruana was a little unnerved by the intensity of the situation, because Black developed smoothly and after some deft manoeuvring with his knight (10…Nf8!) and Q-side castling, got an advantageous position by forcing White’s knight to occupy a poor square on h5. Carlsen sacrificed his f6-pawn on move 21, and after Caruana accepted the sacrifice Carlsen obtained what looked like a winning attack, combining invasions with the rook down the open g-file and the queen on the weak dark squares in White’s Q-side. Caruana was deep in time trouble, having only the 30-second increment to make each of his moves. The critical moment [Game 1 diagram] came at move 38. Commentators and engines alike were screaming for the rook invasion/exchange sacrifice with Rg3! after which Black’s Q mops up White’s Q-side pawns and White’s position crumbles. Carlsen thought he could win without sacrificing material and played 38…Be5 instead, but this allowed Caruana to trade the queens off, and not long after they reached a rook and pawn ending where Carlsen had an extra pawn, but all the pawns were on one side. This is the kind of position that Carlsen can play for hours, torturing his opponent and waiting for them to crack. They played on until move 115 – more than 7 hours play and one of the longest games in World Chess Championship history – but Caruana didn’t crack.

Both players would have had mixed feelings, with Caruana concerned at how easily he was outplayed in the middle game, but pleased to hold the draw, while for Carlsen, the satisfaction of out-preparing Caruana with Black and getting an advantage had to be weighed against the frustration of letting the win slip through his grasp, a repeat of his failure at the Sinquefield Cup. That frustration would have been even greater had he known that this game would be his best chance of winning a game in the entire match. By the time another such chance presented itself in Game 12, Carlsen would no longer be in the frame of mind to fight for victory.

It was probably too much to expect that the match would continue in the vein of Game 1, and indeed the next four games were not as exciting. While they had their intriguing moments, these remained in the wings rather than appearing on the main stage. In Game 2, for example, after Carlsen opened with 1.d4, a Queen’s Gambit Declined appeared on the board, an opening with a long and venerable history in World Championship matches. This time it was Caruana’s turn to surprise with the Black pieces – his move 10…Rd8!? [Game 2 diagram] caught Carlsen unawares, with Carlsen’s face expressing an almost comical look of surprise. The most testing reply here would have been 11.Nd2 threatening Nb3 to attack the Black Queen whose escape has just been cut off by its own Rook on d8. This leads to very sharp and complicated play. Carlsen, clearly uncomfortable with the thought of entering some complicated prepared variation, avoided it with 11.Be2, but he got no advantage out of the opening and was actually worse in the endgame, even though he held the draw comfortably.

Game 3 was another Sicilian Rossolimo, this time more to Caruana’s liking. The opening went well for him, and had he played 15.Rxa5! [Game 3 diagram] he could have gained control of both the a-file and the a2-g8 diagonal and put Black in a difficult position. Unfortunately for him, he only realised this moments after playing 15.Bd2, after which Black was able to contest the control of the a-file (15.Raa8!), use it to exchange off all the heavy pieces, and enter an endgame where if anyone was slightly better, it was Black.

Carlsen switched openings in Game 4, playing the English Opening with 1.c4, apparently part of a match strategy to blunt Caruana’s renowned opening preparation by playing many different openings. But the middlegame position that arose on the board was as dry as dust and a draw was the inevitable result.

Game 5 saw the third Rossolimo of the match, and Caruana ventured a rarely-seen gambit with the move 6.b4!? It turned out that Carlsen had faced this move once before, all the way back in 2004 when he was still just a promising 13-year old wunderkind. He picked his way carefully through the complications and again drew without stress. It was in the press conference after this game that Magnus, asked to name which player from chess history he most admired, answered “myself in 2014”

Finally in Game 6, Magnus tried 1.e4 and allowed Fabi’s pet opening, the Petroff (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nf6) to appear on the board. Well, Magnus walked into the lion’s den – and he very nearly got eaten. The Petroff is a crazy and complicated opening where the normal principles of development, like not moving a piece twice in the opening, seem not to apply. In this game, in the first 14 moves, the players moved only their knights and pawns, and very briefly, their Queens (which were quickly traded.) Still, they reached a normal looking and completely equal middlegame position – the kind of position indeed in which Carlsen usually excels. And then, strangely, Caruana began to outplay the World Champion, and in the Champion’s own style. By move 44, Carlsen felt compelled to sacrifice a piece to reach a worse endgame. By move 58, the man who has said that he doesn’t believe in fortresses (and who has reduced so many of them to rubble – see his defeat of Nakamura in the Sinquefield Cup) felt he had no choice but to sacrifice his a5 pawn in order to construct a fortress of his own. After 68. Bc4?, [Game 6 diagram] Carlsen had proved his skepticism about fortresses to be correct – the Sesse computer chess engine announced a forced mate for Black in 36 moves. But the plan it involved – putting his Knight on g1 and letting it be completely dominated by White’s Bishop, in order to force White into zugzwang — was so deeply hidden and non-obvious that Caruana, understandably, missed it. The chance slipped away and on move 80 the draw was agreed.

At the halfway point, then, six games had produced six draws: a couple of them relatively pedestrian (games 2 & 4), a couple of them intriguing (games 3 & 5), and couple of them both epic and thrilling (game 1 & especially game 6). Both players had had a chance to win one game, though Fabi had less cause for regret than Magnus, since the win he missed in Game 6 was a long computer line in a tense and fascinating endgame that probably no human player could have found over the board. Carlsen’s miss in Game 1 was quite a bit easier to find, and the longer the match went on without presenting him with another such opportunity, the more he must have rued having missed this one. Although it should also be said that Carlsen is famously robust against regrets – it’s one of his great psychological strengths as a player.

The opening battle to this point was surprising in a number of ways, the biggest surprise being that neither player had achieved anything much with the White pieces. One mystery was Fabi’s first choosing and then persisting with the Rossolimo with 3.Bb5 instead of the Open Sicilian with 3.d4. The latter opening has many sharp lines of the kind Caruana is thought to prefer, so why was Fabi avoiding it? Perhaps, not having expected to face the Sicilian, his team needed time to decide what paths to take through the thickets of complications that awaited the players there.

True to form in his own way, and clearly following a match strategy, Carlsen played a different opening move in each of his first three White games. But he failed to get an advantage in any of them: 1.d4 led to a Queen’s Gambit Declined in Game 2, but Carlsen got nothing and Black was better in the endgame. 1.c4 in Game 4 led to an English, Four Knights Variation and the dullest game of the first half of the match, which never left the zone of equality. And 1.e4 in Game 6 led to a position that should have been equal, but which in the end Carlsen was lucky to escape from with a draw.

The match was even more delicately balanced after 6 games than it was when the match began. Magnus retained the advantage he started with, that he would be heavily favoured if the match reached tiebreaks. But the pressure was increasing with each game. In his 2016 match against Karjakin, Carlsen went behind 1-0 in the match before recovering to level the scores and winning the tiebreaks. Carlsen was perilously close to losing in Game 6, and Caruana’s superb positional play confirmed the impression that there’s no difference between them in ability.

The Second Half

I’d wondered whether Carlsen might have a plan to open with a different move in every White game of his, and so whether we might see the Reti Opening in Game 7 with 1.Nf3. But no – Carlsen returned to 1.d4, and in fact they followed the opening moves of Game 2 – a Queen’s Gambit Declined – for 9 moves.

Here in Game 7, Carlsen deviated first and played 10.Nd2 instead of 10.Rd1, but Caruana surprised him again, this time by immediately retreating the Q with 10.Qd8, an exceedingly rare continuation in this position. After Carlsen attacked Caruana’s B with 11.Nb3, Caruana sprang another surprise by retreating with 11…Bb6, which has never been seen before in high level play (in other games, 11…Be7 was played). But the idea of leaving the e7 square vacant for the Q seems to be a good one. Just as he had in Game 2, Carlsen went into a very long think, at the end of which he avoided all the sharp and complicated lines that would arise after either 12.Rd1 or 12.O-O-O, and played, once again, the tame 12.Be2. And once again, he got nothing, and the game fizzled out to a draw after 40 moves.

The signs were ominous for Carlsen. These two games with White were supposed to have been his best chance to put pressure on Caruana. Instead he only barely survived in Game 6 and got no advantage at all in Game 7. His match strategy of trying to blunt Caruana’s preparation by playing different openings with White wasn’t working. Caruana was better prepared, and Carlsen knew it, which is why at crucial moments like those in Game 2 and here again Game 7, he avoided the most testing lines, fearing to go into complicated positions that Caruana has studied. But in so doing he gave up any chance at obtaining an advantage. If he was going to beat Caruana before the tiebreaks, he was going to have to take a risk. The big question hanging over the match was whether he would have the courage to do that, or whether he was playing for the tiebreaks knowing the significant advantage he has there.

Finally, in Game 8, Caruana set aside the Rossolimo and played the Open Sicilian with 3.d4. And, as quite few observers had predicted, a Sveshnikov appeared on the board: 3…cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 e5 attacking White’s knight. After 6.Ndb5 d6, Caruana was the first to step off the beaten path: instead of the usual 7.Bg5, he played 7.Nd5. This forced the exchange of knights, and after 7…Nxd5 8.exd5 a dynamically imbalanced position appeared on the board: White has a Q-side pawn majority and will play there, while Black has a K-side pawn majority and will want to advance them to attack the White King. But Carlsen played a few inaccurate moves (eg 13…a6, where merely allows the Knight to get to where it wants to go anyway, the b6-square), and then, under pressure, lashed out with 18…g5. The move was premature and seriously weakened the light squares around his King, and White got a serious advantage. The critical moment came at move 24 [Game 8 diagram]. Yesterday’s warning sirens had escalated into emergency klaxons. With Qh5, White could have pressed his advantage by invading Black’s K-side with his Q, and Black is probably lost. But Caruana couldn’t quite see how to make it work, and, worried about Black playing …g4, prevented it with 24.h3. This slowed his attack by one crucial move, giving Black time to prevent Qh5 with 24…Qe8. After this, White’s advantage was gone and the game fairly quickly reached a drawn endgame. The draw was agreed on move 38.

Another narrow escape for Carlsen! But more worrying signs. For the first time in the match, White got a serious advantage, and it was Caruana with the chance.

Game 9. Boxing metaphors are always close to hand in World Chess Championships – ‘two heavyweight contenders slugging it out’. After Carlsen’s escapes in Game 6 and especially in Game 8, one could easily think of him as being ‘on the ropes’. But no participant in one of these matches has ever turned up to a game, as Carlsen did for this game, with a literal black eye – the result of a clash of heads with a Norwegian reporter during a soccer game Carlsen was playing on the rest day. His right eyebrow sported a small plaster but fortunately he was not in any pain. He would not have wanted to face Caruana either with a headache, or with his mind dulled by painkillers.

There was no sign of any dullness of mind at the beginning of the game. For the first time in the match, Carlsen got something out of the opening with the White pieces, managing to catch Caruana in a position that he was not too well prepared for. Just as he had in the first half of the match, Carlsen followed a 1.d4 game with a 1.c4 game, and they repeated the first 8 moves of Game 4: 1.c4 e5 2.Nc3 Nf6 3.Nf3 Nc6 4.g3 d5 5.cxd5 Nxd5 6.Bg2 Bc5 7.O-O O-O 8.d3 Re8 – the English Opening, Four Knights Variation, also called the Reverse Dragon because White’s K-side pawn set up is exactly what Black adopts in the Sicilian Dragon. In Game 4, Carlsen had tried 9.Bd2 in this position and got nothing, but here he tried the more adventurous 9.Bg5, and this more or less forced Black to exchange on c3 with 9… Nxc3 10.bxc3 and after 10… f6 11.Bc1 White has achieved two small but significant victories: he has a pawn on c3 covering the d4 square, which prevents Black’s pieces from using it. as they would very much like to do, and Black’s advance of the pawn to f6 to kick the B away has weakened the a2-g8 diagonal. Caruana played 11… Be6 to protect this diagonal, but Carlsen now played a new move, 12.Bb2, reinforcing his control over d4. Caruana began to spend a long time thinking about his moves, unfamiliar with the position and unsure how to equalise. It seems that he didn’t manage to find the right plan (perhaps 12… Bb6 is a bit too passive?), because by move 17 he was sufficiently uncomfortable (and moreover, an hour behind on the clock) to go in for a simplification of the position with 17…Bxf3 leaving him in an endgame where White is just better and can squeeze the position for a long time without any risk – exactly the kind of position that Magnus loves and is famous for winning. White’s chances here are based on the fact that endings with opposite coloured Bishops, while having a high drawish tendency, do favour the attacking player, who effectively has an extra piece to attack with. And in this position, White has K-side pawn majority, and the position of Black’s K has been slightly weakened by the advance of f6, so it’s only White that can think of attacking.

But to the Champion’s visible frustration, this game provided more evidence for the kernel of truth in his joke that he’s not the player he was four years ago. The key moments came around moves 24 and 25. Magnus played 24.h4 but Fabi responded alertly with 24… g6; Magnus pushed again with 25.h5 trying to prevent Black from playing h5 himself, when his defensive setup would be impregnable. But Fabi, counterintuitively, just took the pawn, accepting the shattering of his K-side pawns but seeing, correctly, that he could get counterplay against White’s K by playing …f5 and …h4. After this, Magnus’ advantage was all gone. They played on until move 56, with Magnus hoping to tempt Fabi into an inaccuracy, but Fabi held the draw comfortably. This was Magnus’ 13th draw in a row (before this match he had played four draws in the last four rounds of the European Club Cup), the longest such sequence in his career.

In the press conference afterwards Magnus criticised the whole plan with 24.h4 as ‘ridiculous’, which seems a bit harsh – perhaps he could have tried building up more slowly with Bc6 (kicking Black’s R to a worse square on f8), Bf3, Kg2 and Rh1 but it’s not clear that this would have yielded anything either – Black then has time to get set up with g6, h5 and Kg7 and it’s hard to see how White can break through. It could well be that Black’s defensive resources are good enough to hold this endgame. Carlsen was terse in the press conference, answering two different questions with very curt ‘no’s. His frustration is understandable, but at least he could be pleased to have finally got some traction with White.

In his Game 9 summary, Russian GM Alex Yermolinsky, who has been doing live commentary and producing video summaries of the games for chess.com, complained that the two players have been too risk-averse during the match. He was specifically critical of Caruana’s decision not to play 14…e4 in that game. “Has anyone ever won a World Championship match without taking risks?” he asked, shaking his head sadly. (Incidentally, Yermolinsky has the best Russian accent of all the commentators, all clotted cream and caviar. I love listening to it.)

Yermolinsky had no complaints about Game 10. Both players took risks in a fantastically complicated battle, and the fact that the game ended in yet another draw was not for lack of trying by the players.

As expected, the two players continued their discussion of the rare 7.Nd5 sideline of the Sicilian Sveshnikov that Caruana has chosen for this match, and they followed the first 11 moves of Game 8. At this moment Caruana did something very clever, making excellent strategic use of his preparation. In this position in Game 8, he played the rare but not unheard of 12.Bd2 with the idea of supporting the pawn push to a5, and rerouting the knight from b5-a3-c4-b6 where it dominates Black’s Q-side. He successfully executed this plan in the game and got an excellent position, and was nearly winning at a certain point. In this game, however, he surprised Carlsen again by playing a completely new move, 12.b4!? The point is not that White gets an advantage, but that the move is new and quite playable, the plans connected with it are new and different, and that Caruana had the chance to study them beforehand, while Carlsen was forced to spend time working out the best way to respond over the board.

Carlsen coped well with this challenge. First he kicked Black’s N away to a3 with 12…a6, then pushed on with 13…a5 to attack the pawn on b4 and break up White’s Q-side pawn structure. After White exchanged on a5 (14.bxa4 Rxa5), White won a tempo against Black’s Rook with 15.Nc4 covering the important squares a5 and b6, and then developed with Be3 also looking at the b6-square. Black got on with his K-side counterplay with 16…f5 and 17…f4 attacking White’s B, which duly landed on b6, forcing Black’s Q to shift to e8.

The position is extremely complex and double-edged. Black’s plan is to attack White’s K directly with his pieces (the Rf8 can go to f6 and h6, the Q to g6, the N and both Bs can also join the attack) and central pawn mass, which can roll threateningly forward. White will attack the weak Black pawns on d6 and b7, try to create passed pawns on the Q-side, advance them, and win that way. Those are the ideas in general but they can be executed concretely in many different ways and it’s just extremely hard to tell over the board which way is the most accurate. Not surprisingly, both players played some inaccurate moves in the sequence that followed, with computers suggesting e.g. that 19.Re1 was stronger than Caruana’s move, 19.Ra3, which tries to combine attack on the Q-side with defence along the open 3rd rank. At move 21, Carlsen thought for over 20 minutes before playing the explosive move 21…b5!? with the idea of offering the pawn as a sacrifice to draw White’s B away from the defence of the K-side. Computers suggest that after 23…Qg5 [Game 10 diagram] White could have accepted the pawn sacrifice with 24.Bxb5, survived the furious Black assault that comes after it and held on to the extra pawn to reach an endgame where he would have excellent winning chances. After the game, Caruana said that he didn’t spent too much time trying to calculate Bxb5 – the move just feels too dangerous and even if he suspected it might lead to an advantage, he could not afford to spend the time it would take to figure that out. And if you play it and you’re wrong, you get mated and the match is probably over. Instead Caruana declined and played 24.g3 to blunt Black’s attack.

Even so, the position remained very sharp: Black’s pawns advanced to e4 and f3 — the dreaded, deadly ‘thorn pawn’ — while White got an advanced passed pawn on b6 supported by a Rook. With the time control at move 40 approaching and both players running short of time, Carlsen tried to lure Caruana into a trap, playing 35…Qe2, which seems to lose the Q if White responds with 36.Qb3+ Kh8 37.c4? But here Black turns the tables with 37…Rxb6! attacking White’s Q while winning the crucial b-pawn and with it the game. But Caruana calmly played 36.Re1, and after the Qs were exchanged they entered into a complex but balanced double-Rook endgame. Neither player stumbled too badly (Carlsen had one wobbly moment with 44.Kd4) and the draw was agreed on move 54.

So, a game worthy of a world championship, but nevertheless another draw – the tenth of the match, the longest-ever drawing streak from the start of a world championship match. They fact that they produced a game like this under extraordinary pressure and knowing that one mistake could be fatal is greatly to their credit. But the scores remain deadlocked at 5-5 with only two games left before the tiebreaks, and a single decisive game could crown the victor with the world champion’s laurel.

I thought that if Carlsen played 1.e4 in Game 11 and allowed a Petroff for the second time in the match, a tense and perhaps climactic battle would ensue. He did, but, disappointingly, it didn’t. Instead we got the dullest game of the match. After 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nf6 3.Nxe5 d6, Carlsen opted for the main line with 4.Nf3 (in Game 6 he had tried the somewhat off-beat 4.Nxd3), and they soon reach a position with symmetrical pawn structures and a single open file. As so often happens in these kinds of positions, the heavy pieces were traded off along the open file and the position simplified into a completely drawn endgame. The suspicion grew that Carlsen was playing for the tiebreaks.

The players had an extra rest day to prepare for the last classical game of the match, and despite the worries about Carlsen’s intentions, again I had high hopes of climactic final game: Caruana’s previous two games with White had both been tense and complex battles in the Sicilian Sveshnikov, and another such battle was in prospect.

That’s how things began, with the 7.Nd5 Sveshnikov making its third appearance in the match. This time, after the exchange on d5 attacking Black’s N on c6, Carlsen was the first to deviate: in the two earlier games he had retreated the N to b8, but here he chose 8…Ne7. This changes the character of the position because White’s pawn on d5 is immediately attacked and has to be defended with 9.c4 (a pawn break that White wants to play at some point, but which Caruana had kept in reserve in the earlier games), while the N cannot find a home on e7 because it blocks the defence of the d6 pawn by the B on f8. So Black is forced to play 9…Ng6. White threatened a nasty discovered check with 10.Qa4, which Black parried with 10…Bd7, but now this B blocks the Queen’s defence of d6, so after 11.Qb4, Black chose to move the B again, this time to f5. Now White tried to exploit the possibly dubious position of the N on g6 playing 12.h4, threatening h5 which would leave the N without a good square to go to, so Black prevented this with 12…h5, a move that Black would rather not have to play since it weakens the g5-square.

There was a repetition of moves with 13.Qa4 Bd7 14.Qb4 Bf5, and the commentators nervously wondered whether Caruana would offer a draw by threefold repetition by playing 15.Qa4, but instead Caruana played 15.Be3, attacking the a7 pawn. Perhaps 15.Bg5 immediately exploiting the weak g5 square would have been more testing. Carlsen advanced the attacked pawn to a6, kicking Caruana’s N back to c3. Carlsen played 16…Qc7 and here Caruana went into his first seriously long think of the game.

He thought for 25 minutes, giving Carlsen a significant advantage on the clock, but the plan he came up with doesn’t seem to have been the most precise. He played 17.g3, and after 17…Be7, preparing to castle, Caruana played 18.f3?! which, while it covers some important squares like e4 and g4, also weakens the protection around his King. Carlsen improved the position of his N with 18…Nf8 (heading for d7 where it looks at c5). Caruana made use of the e4 square with 19.Ne4. After 19…Nd7 20.Bd3 O-O Carlsen’s K was safely tucked away in the corner.

Caruana probably should have castled K-side as well at this point. His K would not have been as safe a Carlsen’s because of the moves g3 and f3, but that still would have been preferable to what he played in the game, the rather startling move 21.Rh2?! Caruana’s idea here was to castle Q-side and prevent the pawn break b5 by bringing the R across the second rank to c2, where it protects the King and allows b5 to be met with cxb5 uncovering an attack on Black’s Q on c7. The problem with this plan is that b5 is not the only pawn break that Black has in the position: Black can also aim for f5, which he achieved on move 23, attacking the N on e4. Caruana’s reaction was again not precise, retreating with the N to f2 instead of advancing to g5.

White’s position is becoming critical and Black can press for a serious advantage. At this point online commentators such as Kasparov and Nakamura were predicting that Black would win the game and the match. Here GM Huschenbeth recommended 25…exf4, which opens the e-file and the long diagonal, both of which can be used by Black’s pieces to attack, and forces White to recapture with 26.Bxf4, which means that White can’t use that B to exchange off the dangerous Black N on c5. Now Black can strike with 26…b5! with a very dangerous attack. But Carlsen did not go in for this: instead he played 25…a5 immediately, and after 26.Qd2 he closed the position down with 26…e4. In the resulting positions Black is always going to be better and he can play for a long time without risk, but that isn’t what Carlsen in mind either: on move 31, despite his superior position he shocked his opponent and disappointed everyone watching the game live and on-line by offerring Caruana a draw, which Caruana accepted. In the press conference afterwards he admitted that he wasn’t feeling mentally ready for a fight and didn’t want to take any risks at all, preferring his chances in the tiebreaks.

This was the 12th draw of the match, but the first to be reached in a complicated middle-game position with lots of play left in it. This is the kind of draw that spectators and fans hate, the more so coming after 11 much more justifiable draws. It’s the kind of draw that the Carlsen of a few years ago was known for never offering – there are no such draws in his matches with Anand and Karjakin. Carlsen’s positional style doesn’t appeal to all chess fans, many of whom want to see swashbuckling play with sacrifices and tactics and checkmate delivered in the middlegame. But at least Carlsen always put up a fight. His draw offer in these circumstances, in a match that had yet to produce a decisive game, in an advantageous position both on the board and on the clock and with so many observers hoping for the match to be decided in ‘regular time’ and not with rapid and possibly blitz games, was a great disappointment to his many fans.

To this point, I hadn’t been barracking for either player in the match – instead hoping just to see exciting chess – but I am an admirer of Magnus’ play. Now I thought that the best thing for chess would be for Fabi to win the tiebreaks. This was partly because I thought Magnus’ risk-averse play deserved its comeuppance, but mostly because I hoped that a loss in the tiebreaks would spur Magnus on to greater things in pursuit of his lost crown, in something like the way that Anatoly Karpov became an even stronger player after his defeat by Garry Kasparov in 1985. I think Carlsen must acknowledge that Caruana was better prepared for this match, and that his reliance on his superiority in the middlegame and endgame is no longer enough to beat his closest rival. To beat Fabi, he will have to compete with him on Fabi’s preferred territory, in the opening.

The Tiebreaks

I thought Fabi’s chances in the tiebreaks were better than the ratings difference between them in shorter time controls suggested. While in classical chess only 3 rating points separate Carlsen (2835) from Caruana (2832), in rapid chess the difference is much larger: Carlsen 2880 – Caruana 2789. This 91 point rating difference corresponds to a 62% win probability in each game, a very significant edge. In blitz, the difference is even starker: 2939 – 2767, a 172 point difference, corresponding to a 73% win probability in each game.

But ratings are not everything. They provide only a crude measure of playing strength and they don’t take into account some important factors. Firstly, neither Carlsen nor Caruana actually play a lot of officially rated rapid and blitz games. We should therefore treat their official ratings in those formats with skepticism. Secondly, ratings are calculated based on games with a wide variety of opponents; you have to be cautious in using them to predict how a long sequence of games between the same two opponents will go. Finally, the psychological advantage was with Caruana – Carlsen had chosen to reach the tiebreaks in this manner and been heavily criticised it; he would be under pressure to justify his decision. Caruana was the underdog and could play with nothing to lose.

In the event, Carlsen again showed again his dominance over shorter time controls. Just as had easily beaten Karjakin in the tiebreaks in 2016, he crushed Caruana in the rapid games, winning the first three games and obviating any need for a fourth. In this way, he perhaps justified his match strategy,

The Aftermath

What is the significance of this meeting for chess and for the two players?

The unbroken sequence of 12 draws in the classical games, and the resolution of the match using rapid tiebreaks for the second time in a row, has strengthened the view that the format of the World Championship has to change. But there are a few different things going on here, and it’s worth trying to separate them. It’s been about hundred years since Emanuel Lasker, the second World Champion, predicted that draws would be the death of chess, and about 25 years since computer chess engines became an indispensable part of every human player’s preparation. Do these 12 draws show that Lasker’s dire prophecy is finally coming true? I don’t think so: the classical deadlock was the result of a match between two extremely strong, evenly-matched players who were both perhaps a little too averse to risk. It is remarkable the neither player committed a game-losing blunder in the whole of the match. The games were all drawn, but few of them were dull. Games 1, 8 and 12 probably should have been decisive, Game 10 easily could have been, and Game 6 was winning for Black at one moment, even if that was very hard to see at the time.

A popular suggestion is that the matches should be longer. Personally, I’m nostalgic for the 24-game matches of the Kasparov-Karpov era (1985-1990), but even if that is unrealistic in today’s environment (a 24-game match would take 5-6 weeks to play), a return to a 16-game or 18-game format seems both possible and desirable. Carlsen himself spoke in favour of this idea during the match. But while this probably would reduce the chances of a tied match, I don’t think that’s the reason to do it: it’s worth recalling that the Kasparov-Karpov match of 1987 finished 12-12 after 24 games (on which, more below). Both players won 4 games, and this is the point: more decisive games don’t guarantee a decisive overall result.

In my view, the real reason to play longer matches is connected to the question of what World Championship matches are for, beyond the obvious matter of determining the winner. Chess is a universe, and chess players and fans, now assisted by their computer creations, find beauty and meaning in the exploration of that universe. World Championship matches are often, and rightly, described in the metaphors of conversation and debate: in this match, for example, the two players ‘discussed’ the Rossolimo and the Sveshnikov. The pleasure and the significance of World Chess Championship matches lies as much in what is revealed in these rare, extended conversations between the best exponents of the art, as it does in who wins. The encounters between Kasparov and Karpov gave us many such conversations, in the Gruenfeld, the Nimzo-Indian, the King’s Indian, the Queen’s Gambit Declined, the Ruy Lopez. In a longer match we might have found out, for example, what happens if White plays 11.Nd2 in the Queen’s Gambit Declined position that arose in Game 2, or what Carlsen had prepared in the main line of the Sveshnikov after 6.Bg5. The true sadness of the 12-game format is therefore not the increased possibility of tied matches, but the lost opportunities for the revelation of beauty.

That leaves unresolved the question of what to do about tied matches. Not everyone thinks there’s a problem: Carlsen, perhaps not surprisingly given how he plays the game, thinks that there should be more involvement of rapid chess in the World Championship, not less; that the shorter time controls produce a ‘purer’ form of chess, that is, a battle of instinct and calculation over the board, not of preparation before it. But that’s a minority view; most people think that the Classical World Championship should not be decided by playing rapid and blitz games – the shorter time control games have their own championships. So, what to do? I think the 1987 match I referred to above suggests the answer: that match finished tied 12-12, and Kasparov retained his title, because the Champion had draw odds. All four of the Kasparov-Karpov matches after the abandoned unlimited match of 1984/85 were played with draw odds for the Champion, and it makes sense. The title of World Champion is not bestowed for a fixed period – Magnus is not the World Champion of 2018, he is just the World Champion. By history and tradition, to become World Champion one must defeat the World Champion. Not tie with – defeat. So I think that the World Championship matches should return to playing more games, with draw odds for the Champion.

Where does the match leave the two contestants? Caruana’s situation after the match is familiar and easy to understand: he is the ambitious challenger who has just barely been kept at bay; the title of his story is Unfinished Business. He will no doubt redouble his efforts, train and prepare harder, work on his rapid game, and seek to qualify through the Candidates cycle to challenge Carlsen again in 2020. He will have serious rivals for the privilege: Shakhryar Mamedyarov, the Azeri world #3, has crossed the 2800 rating barrier and hath a mean and hungry look. The Chinese player, Ding Liren recently went 100 games without a single defeat, an incredible record. He is highly motivated to become the first Chinese World Champion. The next Candidates cycle will be another fierce struggle.

For Carlsen, things are much more ambiguous. I said earlier that I hoped that a Caruana victory in this match would spur Magnus on to greater things, that Caruana would be the player who would demand of him an improvement. It’s exciting to imagine what discoveries Magnus might have made in pursuit of his lost title. But his comments after the match showed his thinking running in a different direction: he said that had he lost the match, he might not have tried to regain the title. He would play tournaments, but not participate in the Candidates cycle.

Initially, I found these comments shocking – where is the Champion’s famous fighting spirit? But now I think we can connect them to the questions about Carlsen going into the match, about the decline in his rating since its 2014 peak. It seems that Carlsen is, in fact, a little bored of being the World Champion, and perhaps even a little bored with chess itself. This is sad, but it should not be shocking: he’s 27 years old, and has been playing chess since he was a young boy. He’s achieved everything it is possible to achieve in the game – six years at #1, tournament victories, world championships in every form of the game (classical, rapid, blitz, even Fischer Random), universal recognition as the world’s pre-eminent player. What else is there left to do? Heavy lies the head that wears the crown. Perhaps the constant pressure of being and staying the best in the world has exacted a price: some of his desire to win has curdled into a fear of losing. That’s certainly one way to read his play at the key moments in Games 1 and 12. Perhaps losing to Fabi would have come as a relief, allowing him to lay down the burden of the title and his fear.

But he didn’t lose; he won. In the short term, I expect that Carlsen will be relieved and happy to have the match behind him and not to have to worry about the World Championship for a little while. He’ll have a year’s respite, or a little more. He can play tournaments if he feels like it, and pursue his other interests in modelling, acting and promoting the game. But in March of 2020 his next Challenger will be determined, and then the next defence of his crown will begin to loom. And the questions which at the beginning of this match were merely swirling around, half-unformed and indefinite like dust-devils, will, next time around, be urgent and precise: how much does Magnus Carlsen really want to win?

* * *

Steve Gardner is a pseudo-intellectual dilettante and chess fan. He lives with his wife, two sons and dog in the world’s worst time zone for chess fans: Melbourne, Australia. Apart from chess, he is interested in everything.