by Thomas O’Dwyer

Now that the hundred years have passed, can we wrap up World War I, stick a label on it and dispatch it to the archives of dead history? Otherwise, it’s going to be with us forever. If you are old enough to remember the 1968 events for the 50th anniversary, then you’ve lived to see them happen all over again. The only difference this November has been the absence of interviews with living survivors – there are none left. Harry Patch, the last surviving man to have fought in the trenches at Passchendaele, died in Britain in 2009, aged 111. The last German veteran, Franz Künstler, died in 2008, aged 107. The last veteran from any country, Florence Green from England, who had been in the Women’s Royal Air Force, died in 2012, aged 110.

A notable British film came out around the 50th anniversary – Oh! What a Lovely War, directed by Richard Attenborough. It was a parade of stars – Maggie Smith, Dirk Bogarde, John Gielgud, John Mills, Kenneth More, Laurence Olivier, Jack Hawkins, and three Redgraves (Corin, Michael and Vanessa). They romped through two hours of popular songs parodying the war. It progressed from jingoistic optimism, through the stupidity of the generals and incomprehension of the soldiers, to a vast panorama of white crosses at the end. Attenborough nailed the pointless evil essence of the war (on the Western Front) with touching grandeur and sadness. In background shots, cricket scoreboards tallied the rising death toll in the “great game.”

Is it possible that in 100 years time the world will continue to stand in silence for the war dead on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month?

For younger people today, images of the war may rarely intrude in their busy lives, but can still pop up like creepy cockroaches once a year. World War I lurks in the shadows like death itself. It was the first war where the grim reaper seemed to leave the battlefield to visit the people of the world in their own homes. The reaper dragged along nine million killed in combat, and twenty-one million wounded. Many of them returned without arms, legs, noses, or genitals to an uncaring post-war world. Millions of civilians died. In Germany, the war left a bitterness that Adolf Hitler manipulated into another mass slaughter two decades later. The war has lingered with its trench-foot, poison gas clouds and barbed-wire. The ghost of World War I survived and even transcended World War II, staying vivid even after that Nazi atrocity. Broken bodies in the dirty pools of Flanders foreshadowed Hitler’s putrid mass graves and crematoria.

World War I took a peculiar hold of artists and writers, like an uninvited ancient mariner grabbing wedding guests by the elbow. “By thy long grey beard and glittering eye, now wherefore stopp’st thou me?” On the backs of writers, artists and musicians, it still rides through our world, especially on the November anniversary. Its blood-red poppies are pinned to the chests of almost the entire population of Britain. Its memorial poems and music grip the throat and sting the eyes. Even a simple ballad like The Green Fields of France, in memory of an Irish soldier, can still break the hardest heart:

Well how do you now young Willie McBride?

Do you mind if I sit here down by your graveside…

I see by your gravestone you were only nineteen

when you joined the great fallen of 1916.

Well I hope you died quick and I hope you died clean

or Willie McBride, was it slow and obscene?

The war was staggering in its barbarism and stupidity, in its mindless testing of industrial machines for destroying humans. Poison gas, artillery, giant bombs, relentless machine-guns, tanks, planes all strutted in their new theatre of the macabre. “The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori,” sneered the young officer poet Wilfred Owen, who died one week before the guns fell silent in 1918. (The “lie” came from the Roman poet Horace: “It is sweet and honourable to die for one’s country). “I am not concerned with Poetry,” Owen wrote. “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.”

Historians may one day agree there was no World War I and II – just one World War that lasted from 1914 to 1945, with a 20-year pause in the middle. Indeed, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch prophetically dismissed the 1919 Treaty of Versailles as “an armistice for twenty years.” World War II began twenty years and 65 days after he said it. The first war began in absurdity, unlike more grand strategic wars of previous eras. A local hothead shoots an old reactionary on a bridge in an obscure Balkan town. There should have been a few days of Central European outrage and hand-wringing, before the death of Archduke Franz Ferdinand slipped to the back pages and then to footnotes.

Instead, the crack of Gavrilo Princip’s pistol was like a gunshot in the winter Alps. A bang, a few echoes, a brief silence, and then an avalanche began, sweeping snow sheets along until it roared through peaceful villages that suspected nothing – and kept on going. Austria declared war on Serbia. Russia declared war on Austria and soon it was a free for all as the glaciers of Britain, Germany and France begin to slide. The avalanche to end all avalanches, a brief winter event, everyone thought. It would all be over by Christmas. In a jolly imperial romp, the allies would poke the Kaiser’s eye, then get back to the game of shifting global alliances around like chess pieces. Attenborough’s Lovely War film could have used a T.S. Eliot quote as a tagline: “We had the experience but missed the meaning, / And approach to the meaning restores the experience.”

The war did produce some memorable literary milestones – the poems of Wilfred Owen and his mentor Siegfried Sassoon. From the German side came Erich Maria Remarque’s chilling All Quiet on the Western Front. T.E. Lawrence of Arabia’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom covered the Arab war against the Ottoman Empire. Lawrence reminds us there were many other fronts in this monstrous conflict. The British-led forces fought the Turks in Egypt, Mesopotamia, Arabia and Palestine. In northern Italy, Austrian and Italian troops clashed in twelve brutal battles along the Isonzo River on the border between the two countries.

But it was photographers who produced the images that have haunted the generations since the carnage ended. They exposed the army recruiters’ lie of the war as a dulce-et-decorum romantic adventure in the French countryside. We still have their bleak vistas of pockmarked mud plains, barbed-wire fences, the smoke of shell blasts in the sky instead of clouds. And the greasy trenches, of course, filled with vermin-infested men who would become the walking dead on the ridges. One man gets a haircut beside the body of a comrade, another shaves in a cranny using half of a broken mirror wedged in a dead root. To visit the former battlefields today is to experience more unreality than the men who faced the stripped, cold horror of it all. There are green plains, perky tree lines, gentle mounds and hollows where the ragged trenches crawled. And of course, the graves – pristine, lined up (like soldiers), stretching to horizons. How tidy it all looks compared to the photographs of scattered and broken bodies on the black battlefield. There lay the limbs, randomly chosen by artillery and machine guns, randomly dispersed in death. Now that they lie in rows beneath tidy tombstones, it would seem the time has come to let them depart from our collective memory at last.

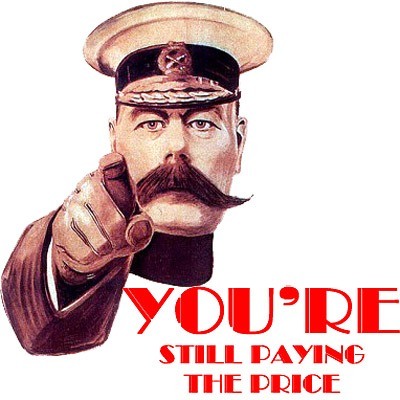

When did World War I one start to mean anything to the young of the later generations? There is the mystery of the Western flappers who danced and partied their way through the 1920s. They were flimsy butterflies, emerged from a giant chrysalis that developed in the crannies of the home fronts during the war. Or in the munitions factories where women, freed from domestic bondage in their own homes or as servants to the upper classes, developed wings they never knew they had. How long has this wretched war been with us? Some call it a cloud hovering over the past century, occasionally blotting out the sun, casting shadows over all the progress we have made. The Middle East is still paying the price for the arbitrary carving up of Arab lands. The British and French imperial fiefdoms paid no respect to religious, tribal or cultural borders. Russia withdrew from the hot war, turned communist, and gave us seventy years of Cold War instead. And we thought we had heard the last of Bosnia and Herzegovina until another cancerous Balkan war erupted in the 1990s.

The legacy of World War I is more subterranean than cloudy. It is a network of geopolitical sewers beneath our feet. Black, stinking and gurgling, they remain an oozing mass of bloodstained mud and horse manure and decomposed bodies. There is an aural miasma of screams, explosions, wailings and neighings. We can hear whistling shells, sudden silences, snatches of songs. It’s a long way to everywhere. If you stand on the manicured neatness of the Flanders and Somme cemeteries, you know it is all still there – all that horror sank down to the other side of the grass. The memory might not fade; it might grow sharper and deeper in continuing post-traumatic flashbacks. Many young people interviewed during the memorial events this month said that they too would continue to remember. Next year and the years after, they would bequeath the memories to their children and grandchildren. They would recall tales of their great-grandfathers, great-uncles and their extended ancestry. For Willie McBride:

In some faithful heart you’re forever enshrined,

and although you died back in 1916,

in that faithful heart you’re forever nineteen.

The world underestimated the time World War I would live on in memories, as it underestimated the space the killing fields would occupy. That space expanded from Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Austro-Hungary, Russia to the Dardanelles, Greek and Bulgarian fronts, Arabia, Mesopotamia, Palestine, Syria. We underestimated the number of people whose lifeblood the trenches – like vacuum tubes – would suck up. There were Indians and Americans; Australians, New Zealanders and Canadians; Germans, Irish and Italians; Arabs and Turks, Russians and even Chinese labourers. They were all creeds and colours, blacks, whites and browns. Death may have dominion but at least it has no discrimination, unlike the brothers in arms did. America’s Harlem Hell Raisers, for example, fought and died with ferocious patriotism, like everyone else. And then they returned to the land whose freedom they had championed to be trodden under like insects. They were forgotten black shadows in the whiteness, and paid little better than slaves for doing whatever dirty jobs anyone would give them. Oh! What an ugly peace.

And so the world waited in denial, waiting for the “armistice” to end, waiting for the beast coming again, slouching to Berlin to be reborn. The white folks had some good times to the beat of some good black music before the Gatsby 1920s faded into 1930s depression, and nobody could spare a dime. And still, the old war burbled up in ominous little volcanic outbursts here and there – Russia, China, Japan, Spain, Ethiopia (Abyssinia). Rehearsals, testing more horror tactics. Guernica destroyed? That looks promising, cooed the German fascists. Nationalism beats patriotism hands down. No one learned lessons, perhaps no one ever will. For all its evolution and self-referential achievements, homo sapiens is the most brutal and insane custodian of the planet since the dinosaurs. We fill these graveyards while exercising reason, rationality, good intentions, even art – and clever lies. World War I, Nazis, Holocaust, Vietnam, Iraq, Srebrenica, Rwanda, Syria and Yemen today. Speak not of “lessons learned.” We must hope that there are no other faunas like us out there, somewhere in the universe. If there are, let us more fervently hope that they never find us.

Now Willie McBride, I can’t help wonder why.

Do those who lie here, do they know why they died?…

The killing, the dying, was all done in vain

for young Willie McBride, it’s all happened again;

and again, and again, and again and again.