by Thomas Manuel

Recently, the BBC published a report on the experience of fake news in India titled ‘Duty, Identity, Credibility: Fake news and the ordinary citizen in India’. The report primarily consists of two parts. The first section is based on 40 interviews with Indian citizens and a week-long analysis of their social media habits. The second section is a network analysis of India’s fake news ecosystem on social media. In the former, they included a list of 15 twitter accounts followed by the country’s Prime Minster, Narendra Modi, that were known to have published at least one piece of fake news. This list included OpIndia, arguably the most popular right-wing digital news outlet in India. The website’s prompt and vociferous response in the form of factchecks and editorials provides the perfect opportunity to examine how right-wing media in India counteracts criticism.

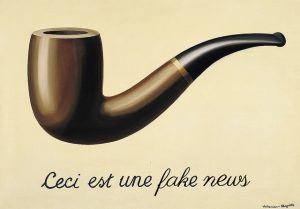

In his essay in EPW Engage[1], Ajay Gudavarthi describes how the Right appropriates ideas from the Left and retools them to achieve the opposite of their original intention: “Right-wing populism has managed to turn the traditional progressive political practices on their head. A critique is absorbed or resignified from its original meaning… it is instructive to observe how the left-liberal critique of the class character of democratic institutions is usurped in legitimising an aggressive state that in fact makes institutions further dysfunctional to the peril of the socially and economically weak and in targeting the religious minorities.” This resonates with how the right-wing relates to journalism and its subordinate traditions. While there are examples of legitimate factchecks from right-wing media, there is simultaneously a fetishization of the vocabulary of fake news, factchecks and debunking.

These terms gained currency after Brexit and the 2016 US Presidential election where they were used to analyse highly successful disinformation campaigns run by right-wing organisations. Factchecking emerged as the primary tool to combat the explosion of disinformation on social media. But the right-wing has usurped this vocabulary, not to combat disinformation or make facts easier to pin down. Rather they enable the right-wing to perform a kind of ‘public’ rationality while still defending the irrational actions of the state. (This is not to say the right-wing is the only source of disinformation; the other political parties in India like the Congress are also guilty but it’s clear that the BJP pioneered the tactic and the rest are rushing to catch up.)

Narrative framing through exaggeration

The keystone of an OpIndia factcheck is the exaggeration of the value of any discrepancies in their target article. Regardless of the extent of their criticism, they compulsively describe targets as being “comprehensively debunked” when they link back to their factchecks from future articles. For example, in their report[2] on The Wire’s investigation[3] of Jay Amit Shah, they find no error in the original report except for a single sentence where the writer mistakenly interprets a negative number as a positive one. The error doesn’t affect the outcome of the article in any way. Their primary allegation against the article is that is full of “innuendo”, i.e., suggesting wrongdoing without ever saying it. This isn’t a revelatory finding. The writer and the editors consciously chose a pared-down style to restrict the article to facts alone so they have a defence for when they are inevitably sued. (They’re on their 6th, I believe.) Based on these findings, i.e., “innuendo” and one meaningless error, OpIndia describes the Wire’s report as “debunked by us comprehensively”. In another factcheck[4], they write that The Wire “insinuate[s] that Piyush Goyal and his family have business ties till date with a defaulting company. Nothing could be further from the truth if one looks at the facts.” The Wire story does insinuate this but despite citing numerous documents and arguing a number of points, the OpIndia factcheckers hardly tackle the basic claim at all. Most of their findings are not debated by the original essay and yet they are presented as evidence of falsity, helping the essay succeed at looking like a legitimate factcheck.

In their factcheck[5] of another story by The Wire[6] on a potential conflict of interest among ministers of the central government, they rephrase the premise. “The subtext of this article,” they write, “clearly attempts to establish guilt by association almost contending that the sons and daughters of serving government officials should not work in institutions that are funded by corporates that might seek contracts from the government…This logic doesn’t hold water by any ethical or industry standard.” This is actually not the conflict of interest that the article describes. Rather, it documents how the Defense Minister was the director of an organisation that solicited sponsorship from corporates for events, explicitly offering the opportunity to meet (and thus lobby) the Defense Minister in return. Much like the previous example, while the article looks structurally like a refutation, no points are actually refuted. Most of the arguments are just flat out wrong.

In their response to the BBC report[7], OpIndia primarily focused on the methodology of the study, hardly engaging with the actual findings. They marshalled three main criticisms: small sample size, reliance on biased sources and two errors. (Of these two errors, one was later shown to be correct while the other was subsequently acknowledged as a mistake.) In their subsequent coverage, the website’s claims become more sensationalized. One column[8] reads, “the BBC broke every single rule of ethical research”, and accused them of cherrypicking their 40 respondents, a baseless allegation. The column also calls for such research to be classified as “fake news”. While bad research can and should be criticized, there is an attempt here to actively and purposely conflate criticism and debunking – a formulation that would allow all research and journalism to be “debunked” regardless of its degree of veracity.

Problems of knowledge and expertise

All forms of populism have some tension with the idea of experts. But this is doubly true for right-wing politics, both in India and abroad, where academia (both ‘hard’ and social sciences) and the media are typically portrayed as hopelessly biased or corrupt. This creates a fundamental contradiction at the heart of right-wing rationality, which needs to lean on institutions of knowledge but none exist that has not been already dismissed. Their only reliable source of information is themselves. (Which is a part of the reason why they compulsively link back to previous articles; each time exaggerating and reinforcing their original claims.)

In their criticism of the BBC’s methodologies, OpIndia doesn’t seek to rely on the opinion of a reputable social scientist to argue that the sample size is too small or that the ethnographic method is unsuitable for generalization, instead they turn to the support documentation of SurveyMonkey, “a reputed survey website”. To this they add scientific-sounding gloss, writing, “by the law of large numbers and Central Limit Theorem, the bare minimum requirement for sample size is 30 (n=30) to ensure that the sample is equally representative.” They finally conclude that “the shoddy sample size alone should be grounds to dismiss this report by BBC as bogus, propaganda driven and motivated.”

When the BBC responded by saying that the report was qualitative research and not a market survey, they were not impressed: “One of the ontological positions of Qualitative Research is that there are multiple realities and that there is no single objective truth. The purpose of Qualitative Research is not to arrive at objective truths that can apply across all situations but to generate hypotheses that could be tested using Quantitative methods.” While there is a lot to unpack in this statement, it’s safe to say that questioning the idea of objective truth is a bit deep for a factcheck.

In a subsequent column[9], they further attack on the report’s methodology, calling it “qualitatively garbage” and “bogus”. The same column continues, “[W]hatever findings the BBC observed from their study can be said to hold true only for those set of 40 people at its worst and maybe, just may [sic], for other groups which bear a close resemblance to that particular group of 40 people. The Qualitative study does not reveal a single thing about the phenomenon of Fake News beyond that which could be generalized for other groups.” While it is valid that these findings cannot be generalized too greatly, they are evidence of media exaggeration. The research remains far from being “debunked”.

Ideological bias and tainted association

As mentioned previously, apart from the sample size, the majority of the original criticism of the BBC report revolved around the use of biased sources. This has two parts. First, the report frames the fake news problem by citing news articles authored by left-leaning journalists. Second, the report uses factcheckers whose neutrality is questioned by OpIndia. The latter is by far the more egregious charge. OpIndia and others were classified (as social media accounts that had shared at least one piece of fake news) based on data received from three factcheckers – BoomLive, Factchecker.in and AltNews. And as OpIndia quite rightly points out, BBC’s definition of fake news is so wide (“information…not fully supported by factual evidence”) that the majority of India’s media ecosystem would be guilty of sharing at least one, even if by error.

Based on this and a slew of older reports, they argue that AltNews and Factchecker.in are partisan in outlook. Most of these older reports involve them factchecking the factchecks of these factcheckers and labelling their claims of fake news as fake news. While many of these reports suffer from the same flaws as mentioned in the above cases, that analysis will have to wait for a future essay. The claim of the report being tainted by association with incompetent or ideologically-biased factcheckers will rest on the veracity of these older reports.

Footnotes:

[1] How BJP Appropriated the Idea of Equality to Create a Divided India, Economic and Political Weekly, 28th April 2018

[2] The Jay Amit Shah story: Low on Facts, High on innuendo, OpIndia.com, 8th October 2017

[3] The Golden Touch of Jay Amit Shah, The Wire, 8th October 2017

[4] ‘The Wire’ spins another lying web, this time, to target Piyush Goyal, OpIndia.com, 3rd April 2018

[5] This ‘The Wire’ hitjob is shoddier than the last, OpIndia.com, 4th November 2017

[6] Exclusive: Think-Tank Run by NSA Ajit Doval’s Son Has Conflict of Interest Writ Large, The Wire, 04th November 2017

[7] The BBC research on ‘fake news’ is shoddy, unethical, dishonest, and actually an example of fake news, OpIndia.com, 15th November 2018

[8] Dear BBC, unscientific research is fake news, OpIndia.com, 21st November 2018

[9] Qualitatively garbage: The bogus methodology employed by BBC in their research on ‘Fake News’, OpIndia.com, 16th November 2018