by Jackson Arn

Writing seriously about comedy is a thankless challenge. Only an idiot, or somebody who’s used to thankless challenges because he’s a freelance critic, would bother. The risks are high, the rewards low. Overanalyze your subject and you’ll kill it. Treat it too indulgently and you’re left with a jumble of second-hand bits. Clearly, jokes say something important about the society that laughs at them, but woe to the writer who takes them too literally or too earnestly. They are, after all, jokes.

Sometimes, comedy changes so profoundly that it’s worth risking some kind of grand, straight-faced interpretation. And mainstream American comedy has changed profoundly in the last thirty-ish years. It’s gotten thinner, lighter, you could almost say healthier. The style of humor that nourished America for decades has dried up—it’s still possible to find it if you know what to look for, but it’s become the exception where it used to be the rule. To put it another way: comedy has been drained of chicken fat. Where did it go?

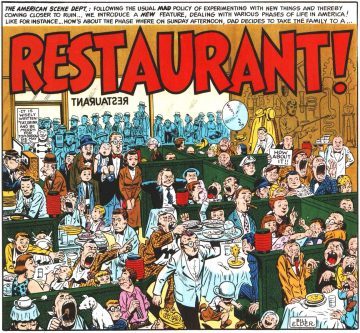

If my subject is chicken fat, I have to start with Mad Magazine. No humor source—not SNL, not Carson, not Lenny Bruce—had as much influence on America in the back half of the 20th century. This is impossible to prove, and almost certainly true. Mad was founded in 1952 and lasted until 2019, when it announced it would stop printing new material. At its peak it had two million subscribers. It made its reputation poking fun at McCarthy and Khrushchev and lasted long enough to take on Trump and Putin. Read more »

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a  In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

In the Age of Trump, the banality of evil can perhaps best be defined as unfettered self-interest. Banal because everyone has self-interest, and because American culture expects and even celebrates its most gratuitous pursuits and expressions. Evil because, when unchecked, self-interest leads not only to intolerable disparities in wealth and power, but eventually the erosion of democratic norms.

In the Age of Trump, the banality of evil can perhaps best be defined as unfettered self-interest. Banal because everyone has self-interest, and because American culture expects and even celebrates its most gratuitous pursuits and expressions. Evil because, when unchecked, self-interest leads not only to intolerable disparities in wealth and power, but eventually the erosion of democratic norms. I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil.

I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil. Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.