by Fabio Tollon

You’ve heard about AI. Either it’s coming for your job (automation), your partner (sex robots), or your internet history (targeted adverts). Each of the aforementioned represent very serious threats (or improvements, depending on your predilections) to the economy, romantic relationships, and the nature of privacy and consent respectively. But what exactly is Artificial Intelligence? The “artificial” part seems self-explanatory: entities are artificial in the sense that they are manufactured by humans out of pre-existing materials. But what about the so-called “intelligence” of these systems?

Our own intelligence has been an object of inquiry for human beings for thousands of years, as we have been attempting to figure out how a collection of bits of matter in motion (ourselves) can perceive, predict, manipulate and understand the world around us. Artificial Intelligence, as eloquently surmised by Keith Frankish and William Ramsey, is

“a cross-disciplinary approach to understanding, modeling, and replicating intelligence and cognitive processes by invoking various computational, mathematical, logical, mechanical, and even biological principles and devices.”

AI attempts not just to understand intelligent systems, but also to build and design them. Interestingly enough, it may be the case that we could in fact design and build an “intelligent” system without understanding the nature of intelligence at all. Important to keep in mind here is the distinction between narrow (or domain specific) and broad (or general) AI. Narrow AI are systems that are optimized for performing one specific task, whereas broad AI systems aim at replicating (and surpassing) many (if not all) capacities associated with human intelligence. Read more »

By 2025, protective living communities (PLCs) had started to form. The earliest PLCs, such as New Promise and New New Babylon, based themselves on rationalist doctrines: decisions informed by best available science, and either utilitarian ethics or Rawlsian principles of justice (principally, respect for individual autonomy and a concern to improve the lives of those most disadvantaged). Membership in these communities was exclusive and tightly guarded, and they had the advantage of the relatively higher levels of wealth controlled by their members.

By 2025, protective living communities (PLCs) had started to form. The earliest PLCs, such as New Promise and New New Babylon, based themselves on rationalist doctrines: decisions informed by best available science, and either utilitarian ethics or Rawlsian principles of justice (principally, respect for individual autonomy and a concern to improve the lives of those most disadvantaged). Membership in these communities was exclusive and tightly guarded, and they had the advantage of the relatively higher levels of wealth controlled by their members.

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose. Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

by Paul Braterman

by Paul Braterman

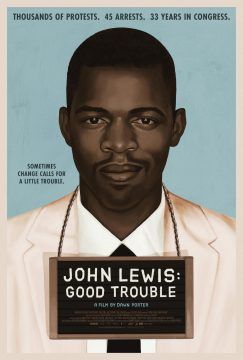

John Lewis: Good Trouble

John Lewis: Good Trouble