by David Copp and Gerald Dworkin

We have argued in a recent article in 3 Quarks Daily that there is a moral obligation for those who are able to safely be vaccinated against serious diseases such as measles and COVID-19 to do so. The gist of the argument is that, when certain factual conditions are met, people have a duty to accept vaccination. There are two conditions. First, there is a significant benefit to the person who is vaccinated and little risk. Second, there is a significant benefit to those to whom the person might otherwise transmit the disease. The benefit is a reduction in the risk of serious harm, which obtains if the disease is life-threatening or seriously threatening of significant pain, physical or emotional damage, or significant expense or effort to avoid these, to a significant subset of the population. We will refer again to these conditions, so let’s have a term for them. Call them the “factual preconditions” of an obligation to accept vaccination.

We have argued in a recent article in 3 Quarks Daily that there is a moral obligation for those who are able to safely be vaccinated against serious diseases such as measles and COVID-19 to do so. The gist of the argument is that, when certain factual conditions are met, people have a duty to accept vaccination. There are two conditions. First, there is a significant benefit to the person who is vaccinated and little risk. Second, there is a significant benefit to those to whom the person might otherwise transmit the disease. The benefit is a reduction in the risk of serious harm, which obtains if the disease is life-threatening or seriously threatening of significant pain, physical or emotional damage, or significant expense or effort to avoid these, to a significant subset of the population. We will refer again to these conditions, so let’s have a term for them. Call them the “factual preconditions” of an obligation to accept vaccination.

In this essay we are interested in a different set of issues–those surrounding the use of legal coercion to enforce the moral duty above. It is important to see that the two questions are distinct. There are moral obligations that we do not use the law to enforce. For example, we are generally obligated to tell the truth. People often lie when they are obligated not to do so. But lying is not generally a criminal offense. Suppose that someone who is seriously hurt and trying to get to an emergency room in his car, asks us where the nearest emergency room is. If we gave him false directions, we would clearly be failing to comply with a moral obligation to tell the truth in such circumstances. But, to our knowledge there is no law which requires us to tell the truth in such a circumstance. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Island Pond Algae, Upstate NY. July 26, 2020.

Sughra Raza. Island Pond Algae, Upstate NY. July 26, 2020.

Nothing focuses minds like grave events that bring about severe disruption to everyday living. Over recent times, two major happenings, one with global and the other with more regional implications, have jolted people out of their complacency and compelled some reflection on unpredictability and uncertainty in life, and what is going on around us.

Nothing focuses minds like grave events that bring about severe disruption to everyday living. Over recent times, two major happenings, one with global and the other with more regional implications, have jolted people out of their complacency and compelled some reflection on unpredictability and uncertainty in life, and what is going on around us. When the Rajah’s barber could no longer keep the secret, he was seen darting by the sparrow in the tamarind, by the flinty owl in the giant oak that was surely a jinn’s abode, by a flock of hill mynahs flying through the buttery light of early spring. What was it that sent him bumbling through the jungle like that? Hours before, he had met the Rajah’s terrible gaze in the mirror when he discovered two sickle-shaped horns under his hair. This secret was as a rock he had swallowed, a rock he needed to expel. He was found panting by the fox of the jungle’s dank center, by a tightly knotted vine clutching a forgotten well. He saw that the well was old and there was bamboo growing in it. He saw it was safe and he screamed his fullest scream into the well: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret and happily soaked it up, but the next day it was cut down by a flute maker who had been in search of just the right bamboo. Soon, all his fine bamboo flutes were sold. Then, all the new flutes of Jaunpur sang out the secret: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret. The hapless barber had poured into it his last song.

When the Rajah’s barber could no longer keep the secret, he was seen darting by the sparrow in the tamarind, by the flinty owl in the giant oak that was surely a jinn’s abode, by a flock of hill mynahs flying through the buttery light of early spring. What was it that sent him bumbling through the jungle like that? Hours before, he had met the Rajah’s terrible gaze in the mirror when he discovered two sickle-shaped horns under his hair. This secret was as a rock he had swallowed, a rock he needed to expel. He was found panting by the fox of the jungle’s dank center, by a tightly knotted vine clutching a forgotten well. He saw that the well was old and there was bamboo growing in it. He saw it was safe and he screamed his fullest scream into the well: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret and happily soaked it up, but the next day it was cut down by a flute maker who had been in search of just the right bamboo. Soon, all his fine bamboo flutes were sold. Then, all the new flutes of Jaunpur sang out the secret: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret. The hapless barber had poured into it his last song.

Many social commentators in the claustrophobic gloom of their self-isolation have shown a tendency to write in somewhat feverish apocalyptic terms about the near future. Some of them expect the pre-existing dysfunctionalities of social and political institutions to accelerate in the post-pandemic world and anticipate our going down a vicious spiral. Others are a bit more hopeful in envisaging a world where the corona crisis will make people wake up to the deep fault lines it has revealed and try to mend things toward a better world. Some others take an intermediate position of what is called upbeat cynicism: hold out for things to be better but guess that will not happen (somewhat akin to Antonio Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”).

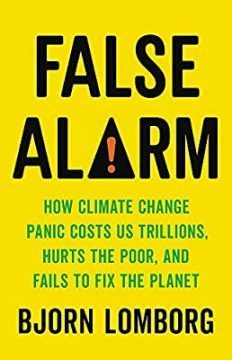

Many social commentators in the claustrophobic gloom of their self-isolation have shown a tendency to write in somewhat feverish apocalyptic terms about the near future. Some of them expect the pre-existing dysfunctionalities of social and political institutions to accelerate in the post-pandemic world and anticipate our going down a vicious spiral. Others are a bit more hopeful in envisaging a world where the corona crisis will make people wake up to the deep fault lines it has revealed and try to mend things toward a better world. Some others take an intermediate position of what is called upbeat cynicism: hold out for things to be better but guess that will not happen (somewhat akin to Antonio Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”). Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.

Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.