by Peter Wells

My mother believed that games were good for you. Her faith was unshaken by the occasions when my brothers and I returned from our outdoor games with a grievance between us, or by the times the Monopoly board was overturned in anger during the winter months. She considered that games were a preparation for life. I think she underestimated them.

My mother believed that games were good for you. Her faith was unshaken by the occasions when my brothers and I returned from our outdoor games with a grievance between us, or by the times the Monopoly board was overturned in anger during the winter months. She considered that games were a preparation for life. I think she underestimated them.

Games require two complementary faculties that are extremely difficult to maintain in tandem at full strength. The first is the ability to take a game absolutely seriously. While it is in progress, it matters. The rules must be obeyed, but participants are encouraged to use their ingenuity to exploit the rules, as well as every facet of their mental and/or physical ability, in order to win. The aim is not primarily skill development, or increased fitness, or social interaction, it is victory, and victory over an enemy doing their best. As soon as we know our opponents are not trying, the game disintegrates. Children quickly learn to spot when their parents are letting them win, and they don’t like it. They would rather suffer repeated defeats than such condescension.

The second faculty is the ability to keep the game self-contained, and not allow it to spill over into the players’ non-game lives, or be vulnerable to their personal character flaws or relationship issues. If the desire to win causes the participants to cheat, become angry, or bear a grudge after defeat, or even to be triumphalist and scornful in victory, the game is ruined. Because it is, after all, ‘a game.’ Note, I did not say ‘only.’ Read more »

first their concerted honks—

first their concerted honks—

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

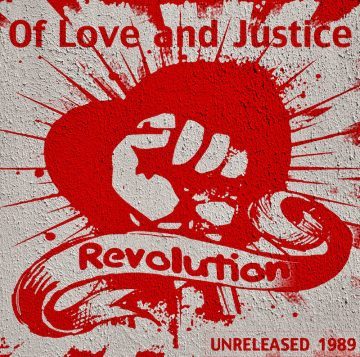

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality. Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.

Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.