by Charlie Huenemann

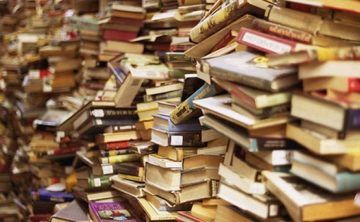

It is commonplace to observe just how marvelous books are. Some person, perhaps from long ago, makes inky marks onto processed pulp from old trees. The ensuing artifact is tossed from hand to hand, carrying its cargo of characters, plots, ideas, and poems across the rough seas of time, until it comes to you. And now you have the chance to share in a tradition of readers stretching back to the author, a transtemporal book club who communicate with one another only by terse comments scratched into the margins of this leather-bound vessel.

It is commonplace to observe just how marvelous books are. Some person, perhaps from long ago, makes inky marks onto processed pulp from old trees. The ensuing artifact is tossed from hand to hand, carrying its cargo of characters, plots, ideas, and poems across the rough seas of time, until it comes to you. And now you have the chance to share in a tradition of readers stretching back to the author, a transtemporal book club who communicate with one another only by terse comments scratched into the margins of this leather-bound vessel.

But, boy, do they pile up over time! Shelves groan under the weight of old textbooks, exclamatory treatments of hot topics long past their sell-by date, endless reissues of classics, sci-fi paperbacks that disintegrate when opened, and that one book on economics you were supposed to return to somebody five, no, maybe ten years ago. Some, perhaps, have resale value. The rest could be dropped into a charity box to join the massive graveyard of books to be boxed up and never seen again.

The remaining option is to dump them unceremoniously into the recycling bin – but most of us recoil from the suggestion in horror. Why? We venerate books as objects. Some books preserve important ideas that threaten bigots and tyrants, and these are the ones often burned by said barbarians. Holding onto these books is one way to affirm their importance in preserving our fragile civilization. Some of these books are old friends to us, our teachers and soulmates, and so dumping them is unthinkable. “Books” as a common noun typically picks out the ones that mean so much to us, and if we were to announce to our friends that we were dumping out our old books, we might as well have said we were doing so on our way to burn down the Parthenon and slap a mustache on the Mona Lisa. Read more »

My mother believed that games were good for you. Her faith was unshaken by the occasions when my brothers and I returned from our outdoor games with a grievance between us, or by the times the Monopoly board was overturned in anger during the winter months. She considered that games were a preparation for life. I think she underestimated them.

My mother believed that games were good for you. Her faith was unshaken by the occasions when my brothers and I returned from our outdoor games with a grievance between us, or by the times the Monopoly board was overturned in anger during the winter months. She considered that games were a preparation for life. I think she underestimated them.

first their concerted honks—

first their concerted honks—

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality. Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.

Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.