by Joseph Shieber

I’ve been reading Stanley Corngold’s surprisingly interesting Walter Kaufmann: Philosopher, Humanist, Heretic. I say “surprisingly interesting” because I only thought of Kaufmann as the author of a dated book on Nietzsche and a number of anthologies on Nietzsche and other existentialist figures.

As it turns out, Kaufmann was a fascinating figure in his own right. Born in Germany in 1921, Kaufmann was raised Lutheran, but, finding that he couldn’t accept the doctrine of the Trinity, Kaufmann converted to Judaism – after the Nazis had already assumed power! – only to find that both his paternal and maternal parents had converted to Lutheranism from Judaism.

Kaufmann spent one year studying for the rabbinate in Berlin before fleeing Nazi German for the United States. Alone in a new country, Kaufmann taught himself English, enrolled at Williams College and then received an M.A. in philosophy at Harvard before joining the U.S. Army in Military Intelligence and returning to Germany, where he served as an interrogator, before returning to complete his Ph.D. in philosophy at Harvard. He then embarked on a 30-year teaching career at Princeton.

Apparently, for all of the stability of his academic career, Kaufmann remained a peripatetic figure. Before his untimely death in 1980 at the age of 59, Kaufmann had already traveled around the world – four times!

Reading Corngold’s chapter on the book that cemented Kaufmann’s reputation, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, I was struck by the ways in which Kaufmann’s own biography must have predestined him to be receptive to Nietzsche’s philosophy. Read more »

1.

1.

Look on the back label of most wine bottles and you will find a tasting note that reads like a fruit basket—a list of various fruit aromas along with a few herb and oak-derived aromas that consumers are likely to find with some more or less dedicated sniffing. You will find a more extensive list of aromas if you visit the winery’s website and find the winemaker’s notes or read wine reviews published in wine magazines or online.

Look on the back label of most wine bottles and you will find a tasting note that reads like a fruit basket—a list of various fruit aromas along with a few herb and oak-derived aromas that consumers are likely to find with some more or less dedicated sniffing. You will find a more extensive list of aromas if you visit the winery’s website and find the winemaker’s notes or read wine reviews published in wine magazines or online. In a recent article in

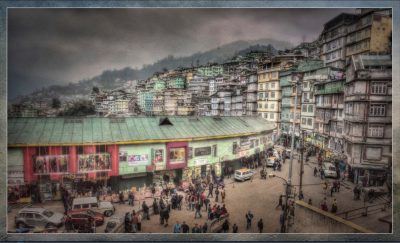

In a recent article in  High in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of northern Colombia, the Kogi people peaceably live and farm. Having isolated themselves in nearly inaccessible mountain hamlets for five hundred years, the Kogi retain the dubious distinction of being the only intact, pre-Columbian civilization in South America. As such, they are also rare representatives of a sustainable farming way of life that persists until the modern era. Yet, more than four decades ago, even they noticed that their highland climate was changing. The trees and grasses that grew around their mountain redoubt, the numbers and kinds of animals they saw, the sizes of lakes and glaciers, the flows of rivers—everything was changing. The Kogi, who refer to themselves as Elder Brother and understand themselves to be custodians of our planet, felt they must warn the world. So in the late 1980s, they sent an emissary to contact the documentary filmmaker, Alan Ereira of the BBC—one of the few people they’d previously met from the outside world. In the resulting film,

High in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of northern Colombia, the Kogi people peaceably live and farm. Having isolated themselves in nearly inaccessible mountain hamlets for five hundred years, the Kogi retain the dubious distinction of being the only intact, pre-Columbian civilization in South America. As such, they are also rare representatives of a sustainable farming way of life that persists until the modern era. Yet, more than four decades ago, even they noticed that their highland climate was changing. The trees and grasses that grew around their mountain redoubt, the numbers and kinds of animals they saw, the sizes of lakes and glaciers, the flows of rivers—everything was changing. The Kogi, who refer to themselves as Elder Brother and understand themselves to be custodians of our planet, felt they must warn the world. So in the late 1980s, they sent an emissary to contact the documentary filmmaker, Alan Ereira of the BBC—one of the few people they’d previously met from the outside world. In the resulting film,

People are basically good.

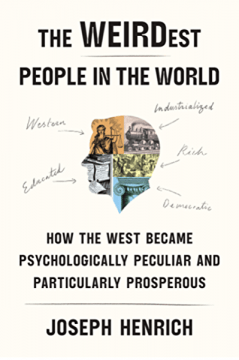

People are basically good. Here’s an interesting game. You receive 20 dollars, and you and three others can anonymously contribute any portion of this amount to a public pool. The amount of money in this pool is then multiplied by 1.5 and divided equally among all players. Repeat 10 times, then go home with your money. What will happen? How much would you contribute in round one, if you knew nothing about your fellow players?

Here’s an interesting game. You receive 20 dollars, and you and three others can anonymously contribute any portion of this amount to a public pool. The amount of money in this pool is then multiplied by 1.5 and divided equally among all players. Repeat 10 times, then go home with your money. What will happen? How much would you contribute in round one, if you knew nothing about your fellow players?