by Bill Murray

The northern Indian province of Sikkim, between Nepal and Bhutan, borders Tibet. To visit, non-Indians require an “Inner Line Permit/Restricted Area Permit” issued by the Government of Sikkim Tourism Department.

It’s because of history. China chased the Dalai Lama from Lhasa over these mountains and off the throne in ’59. India took in his cadre and donated a whole city, Dharmsala, to their cause. The Chinese have raised hurt feelings to high art, and by this those feelings were gravely wounded.

Besides, the Tibet/Sikkim border isn’t drawn to either sides’ satisfaction. These are barren, forbidding, 12,000 foot mountaintops that nearly 2500 people died fighting over in the 1960s. (The border at Nathula only reopened for trade in 2006.) So they like to keep up with where foreigners are.

The Inner Line Permit is a sheet of legal sized pulpy paper with wood chips. You can get one at the provincial border for free with passport photos and photocopies of things. It cautions that we must not overstay or go beyond the restricted areas, and must register at all check posts. It has us commit to paper what Indian intelligence probably already knows: our arrival point, arrival and departure dates, names, nationalities, and passport information. This form requires a bureaucrat’s stamp. The bureaucrat’s stamp is money.

We hurtle to a stop (driving is purposeful here) outside a building labeled Ministry of Handicraft and Handloom and present ourselves and our papers to two gentlemen inside. We wish to enter Sikkim via Rangpo town.

The presiding official wears a Millet brand down jacket with a tall, zipped-tight collar. He examines our materials for several minutes. First, there will be no small talk. This is official business, too grave a matter for that. Nor, for that matter, will there be any cordiality.

I think he’s demanding respect with his silence. TAKE ME SERIOUSLY. This is his domain and these are his number of minutes and it is not our privilege to question or expedite things in any way. Look here now: I can slow down anybody I want.

But the road to Gangtok spreads before us. He holds our progress in his hands right now and we will – if we won’t do anything else – we will note it. He pulls a ledger to his blotter and begins recording our passport and visa details both on the ledger and on our permit.

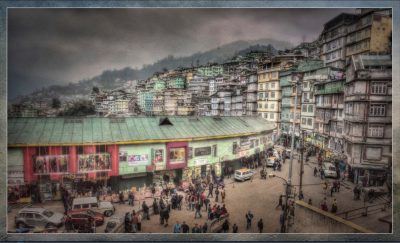

The official and his colleague preside across battered metal desks. Facing them, we have the better view. Picture windows at their backs reveal the permanently stirred up frenzy of the street, and on the other side of it, well, Ricki’s Cocktail King.

The Ministry of Handicraft and Handloom is sort of a rambling, half open, ad hoc thing. A clock ticks and a bird causes a ruckus somewhere up in the rafters.

Ultimately our application to enter Sikkim causes no incident (or uttered syllable), and in time, out comes The Stamp. It pounds around a few places, gathers steam on ink pads and at last lands on our new Inner Line Permit. Naive as we are, we imagine we’ll be on our way.

And underway we are, not to Gangtok but under our driver Sunil’s escort, picking our way on foot across a frenzied lane and a half of pocked tarmac on the road to Sikkim, descending a hill toward a bridge and right past Ricki’s Cocktail King. Must say, I cast a longing gaze.

Chaos prevails over here. Over here, besides clerks in interior rooms, other clerks stand in windows open to the street, windows labeled Excise Tax and Forestry Department and more, pay windows for goods carriers inbound to Sikkim where men stand belligerent and flushed and point and holler. Their vehicles are what causes the frenzy.

We stand facing green pastel walls in an office lit by a swinging bulb. Two new gentlemen. The inferior clerk sits at his superior’s side on a rolling office chair that has no back, wielding sheaves of paper, fretting. The boss man sits behind a half window with space for pushing critical documents back and forth beneath the plexiglass.

Letters on his window spell out “C. O. I. Verification Officer.” The C. O. I. Verification Officer takes our papers, examines them with a practiced eye to detail and, alas, frowns. He wears a high-collared parka similar to the gentleman in the Ministry of Handicraft and Handloom, but it is Kappa brand, not Millet.

With all the joy of a cat in a cloudburst, he reaches for a sheaf of papers like his adjutant’s and begins his work. Which consists of copying our same details into his papers, performing a vital verification, no doubt, of the work of his conniving colleague up the hill.

There will be a delay now, for the inferior clerk riffs his stack of papers, shakes his head and speaks. The C. O. I. Verification Officer puts down his pen and gingerly leans back in his chair. It creaks. It is one of those chairs that at a certain point in its trajectory of recline, collapses all at once the rest of the 45 degrees backward. So the Verification Officer is careful, and when his chair settles without capsizing he and his clerk discuss matters for a time. At length, with no small amount of labor, the officer summons himself upright and hands his clerk a stapler.

Officials stride the length of the old office floors, and you can feel their footfalls through your shoes. A small, older gentlemen enters, putters here and there, then heads back and down the darkness of a hallway. His movement leads my eye to a hand-painted sign farther down, the entrance to the Forestry Department. Between us and the sign an open electrical box on the wall sticks wires out into the hallway, where there is just the faintest smell of piss.

On his own schedule, the C. O. I. Verification Officer completes his work and looks none too happy about it. The Stamp comes out and pounds around the C. O. I. desk and onto our papers. And we are free to go. Silently. Gravely.

•••••

Abidjan is thick with thieves, “beaucoups de bandits,” a driver named Simeon warned us, although in French even bandit sounds genteel (“bawn-dee”).

Normally in these arrivals I opt for studied disengagement, burnished internally with bemusement, for here is the pageant of humanity. But not this time. Just now I am not in the mood for touts who surround your car and open your door for a tip, or stand in the street and wave their arms to guide you into your parking space. Today, just run ‘em over. We’ve flown since predawn, stopping in Bamako, and I have been ill since Cape Town.

Here is a new ruse. The local boys use signs with peoples’ names to get access inside the pass control gates, then make like officials who are going to open another pass control lane for you, grab your passports and expedite you through the lines – which really works – with the acquiescence of the real pass control clerks, for tips.

They’re on you tight as a surgical glove, then the baggage cart cadres pile on just outside the pass control desk. These fellows artfully monopolize every last baggage cart and attach themselves to you. I give the pass control expediter a dollar – we have no local money – and he demands ten. “Get lost,” we explain and finally, at unending length, he does.

Been down this routine. We tell the round little man who appoints himself to help at the bag carousel (additional to the goon with the cart), “We do not want your help, we will not pay you, go away.” He smiles and laughs because that is surely a big joke, and doesn’t move. I say the same words slowly and seriously. He shakes his head, for a terrible wrong has been done him, and slowly, eventually, leaves. But he is back, outside at the curb, for one last try. His cousin is a taxi driver, see….

•••••

Two open aisles confront Citizens and Residents in the arrivals hall, Miami. We’ve just flown the 43 minutes from Havana, March, 2012, during the brief Obama era flirtation with Cuba, on one of nine flights to Florida listed at Jose Marti Airport the morning of our return. (We arrived at U.S. Passport Control with our enabling paperwork, a sort of license to travel to Cuba, at the ready, anticipating red tape. In the event, the agent didn’t bat an eye, just waved us in. “Welcome back.”)

Everyone hurries to fill the queues that snake around way behind the pass control booths. The lines back up pretty quickly. You learn to hustle off the plane because it’s like airport check-in lines in reverse, if you pick a lane where there’s some indefinable problem, or the agent’s just having a bad day, each person in front of you could mean an extra six, eight, ten minutes. (Pro tip: If there is a choice of stairs or escalator between the plane and pass control, ALWAYS hustle up the stairs. Most people don’t.)

You try to discern how many are in what-sized groups. If those two right there are sisters and they approach the clerk at the same time, it may be quicker than if they go separately.

Have you ever been about eleventh in the queue with two booths open and you see an officious agent stride in, as if to open a third? You can’t move too soon, it might be a feint, but if he means to inaugurate his own little fiefdom in booth three, you aim to jump at just the instant to lead the flow to his booth, as soon as he opens, circumventing the ten in front of you. Timing is everything.

You can see the guy now. He’s deliberate, balding enough that he went ahead and shaved his head, sanctimonious maybe a little, with a good posture (they’re all erect and upstanding), young, unhurried, air of authority, intent on Representing Our Country Correctly.

He’ll open his briefcase. He’ll shuffle and arrange his papers. You can’t quite see all the fiddling he’s doing inside the panels surrounding his booth, but you figure he’s turning on his computer. At least, he faces the screen. You’re ninth in line now. You guess his computer has to have a little time to boot up. Maybe you get to talking with the sari-clad woman in front of you. She thinks the guy’s pretty good-looking, you guess, but that’s not what you talk about. You conspire to be the first in his line when he opens.

You read his facial expressions. Is he a helpful kind of guy? Will he hurry to accommodate? Now you’re eighth to the front and you’ve already been here fifteen minutes. Your bags are spinning around on the carousel out there by now. Nah, you decide he’s not going to be your savior. He’s being very deliberate, doing things you can’t see behind the plexiglass. You can still attribute his movements behind his counter to his follow-the-procedures work ethic, if you’re being kind.

You don’t know, maybe he’s getting out his own personal-issue passport stamp and inking it. Whatever he’s doing, he’s doing it behind that glass so you can’t be sure. Now three people move up in a group and now you’re fifth. You’ve had this guy in your sights to save you some time for seven minutes now and you might only have seven to go, but he can still save you those seven.

Fatalistic humor now with the lady in front of you. In another person or so, you’ll have to do a kind of blocking maneuver with your body to both keep your option to go to the new guy’s aisle and keep the people behind you from edging around you. Now you’re fourth. When you’re about third it won’t really matter if he ever opens or not.

He never lifts his eyes outside his booth, like every bartender you’ve ever disdained. You and the woman joke that he’s just back there playing video games, or that his lunch break doesn’t end for four more minutes and he’s not going to go back to work a minute before that.

He turns on the light behind his little sign. He’s ready to go and here is the big crush. Everybody’s been plotting just like you and people crowd into his queue and now you’d be fourth to the front with him – if you go right now – and you’re second where you are. So you stay put. Some guy behind you saves ten minutes.