by Usha Alexander

[This is the sixth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

“The American way of life is not up for negotiation.” —George HW Bush to the assembled international diplomats at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, 1992

“The American way of life is not up for negotiation.” —George HW Bush to the assembled international diplomats at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, 1992

“Much talk. Talking will win you nothing. All the same, the woman goes with me to the house of Hades.” —Thanatos to Apollo in a scene from Alcestis by Euripides, 5th Century, BCE

***

In Classical Greek mythology, Thanatos was Death. As a minor god who got little press in the surviving tales, he appears in the play, Alcestis, as something of a functionary, dutifully gathering those whose time had come and spiriting them to the underworld. Not that he doesn’t find some satisfaction in his work, but he wields his power neither masterfully nor hungrily. The touch of Thanatos did not bring on death from war or violence—those deaths were the domain of other deities—but an ordinary death, as experienced by most. In ancient times, Thanatos was often depicted as a winged youth, as a babe in the arms of his mother, Nyx, goddess of Night, or with his twin, Hypnos, Sleep. Thanatos was not a villain. But he was ruthlessly inevitable.

In the 21st Century Marvel film franchise, Thanatos has been reinvented as Thanos. In this reimagining, Thanos still wields death, but he sees his job in larger terms: he wants to bring peace to the universe, which is engulfed in strife. “Too many mouths. Not enough to go around,” he explains, referring to the overpopulation of the Marvel Universe. Thanos’s solution is to reduce the number of living things through a painless existential cleanse that will magically drift across the universe, gently annihilating half of everybody. He understands himself as the only being possessed of both will and power enough to act upon the need of the hour—to turn every other being into dust, thus restoring balance and enabling peace among the untold trillions who will survive. His desire to erase half of all the living isn’t personal, nor is it inspired by cruelty, venality, or a lust for power. Like his Greek inspiration, Thanos is pragmatic, goal-oriented, and transactional. Though he’s depicted with the stature of a supervillain, in command of limitless legions of grotesque warriors, he’s motivated by a sense of duty: the universe is out of balance and must be set right. “I am inevitable,” he quietly declares. Read more »

Not since the Civil War and Reconstruction has the citizenry in the United States been so divided. In our current

Not since the Civil War and Reconstruction has the citizenry in the United States been so divided. In our current

November 6, 1860. Perhaps the worst day in James Buchanan’s political life. His fears, his sympathies and antipathies, the judgment of the public upon an entire career, all converge into a horrible realty. Abraham Lincoln, of the “Black Republican Party,” has been elected President of the United States.

November 6, 1860. Perhaps the worst day in James Buchanan’s political life. His fears, his sympathies and antipathies, the judgment of the public upon an entire career, all converge into a horrible realty. Abraham Lincoln, of the “Black Republican Party,” has been elected President of the United States.

Back in 1971, I couldn’t have predicted that the release of Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, Blue, would mark the beginning of the end of a friendship.

Back in 1971, I couldn’t have predicted that the release of Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, Blue, would mark the beginning of the end of a friendship.

2020 has been a wild ride, but it’s almost over, and I’m here to tell you it wasn’t all bad, as some great music came out this year – so much, in fact, that we’ll have to have two or even three podcasts this time even for the small taste which is our annual year-end review. Here’s part 1 (widget and link below).

2020 has been a wild ride, but it’s almost over, and I’m here to tell you it wasn’t all bad, as some great music came out this year – so much, in fact, that we’ll have to have two or even three podcasts this time even for the small taste which is our annual year-end review. Here’s part 1 (widget and link below).

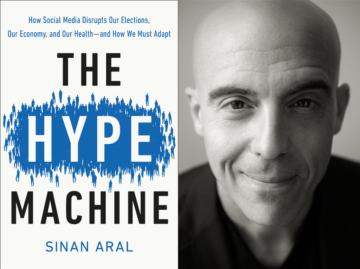

Given where we find ourselves in this late November of 2020, it is hard to think of a book more relevant or timely than The Hype Machine by Sinan Aral. The author is the David Austin Professor of Management and Professor of Information Technology and Marketing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As one of the world’s foremost experts on social media and its effects, Prof. Aral is the perfect person to look at how this phenomenon has changed the world and the human experience. This is what he sets out to do in his new book, The Hype Machine, published under the Currency Imprint of Random House this September, and with considerable success.

Given where we find ourselves in this late November of 2020, it is hard to think of a book more relevant or timely than The Hype Machine by Sinan Aral. The author is the David Austin Professor of Management and Professor of Information Technology and Marketing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As one of the world’s foremost experts on social media and its effects, Prof. Aral is the perfect person to look at how this phenomenon has changed the world and the human experience. This is what he sets out to do in his new book, The Hype Machine, published under the Currency Imprint of Random House this September, and with considerable success. Dylan Kwait. Surfers by Plum Island, October 2020.

Dylan Kwait. Surfers by Plum Island, October 2020.

Not long ago there was an article circulating on Facebook about ‘Hating the English’, originally published in a large circulation newspaper. The Irish author says something to the effect that once she thought it was just a few bad ones etc., but now she hates the lot of them. It’s been stimulated, I think, by the repulsive English nationalism that has been raising its head since Brexit, plus the usual ignorance about Ireland, Irish history and Irish interests on the part of your typical ‘Brit’. It’s not a very good piece of writing, and it has a rather slight idea in it. I’d ignore it but for the ‘likes’ and positive comments it’s received, particularly from ‘leftists’. It’s an example of what we could call ‘bloc thinking’ – the emotionally satisfying but futile consignment of entire masses of people into categories of nice and nasty.

Not long ago there was an article circulating on Facebook about ‘Hating the English’, originally published in a large circulation newspaper. The Irish author says something to the effect that once she thought it was just a few bad ones etc., but now she hates the lot of them. It’s been stimulated, I think, by the repulsive English nationalism that has been raising its head since Brexit, plus the usual ignorance about Ireland, Irish history and Irish interests on the part of your typical ‘Brit’. It’s not a very good piece of writing, and it has a rather slight idea in it. I’d ignore it but for the ‘likes’ and positive comments it’s received, particularly from ‘leftists’. It’s an example of what we could call ‘bloc thinking’ – the emotionally satisfying but futile consignment of entire masses of people into categories of nice and nasty.

According to Donald Trump, in

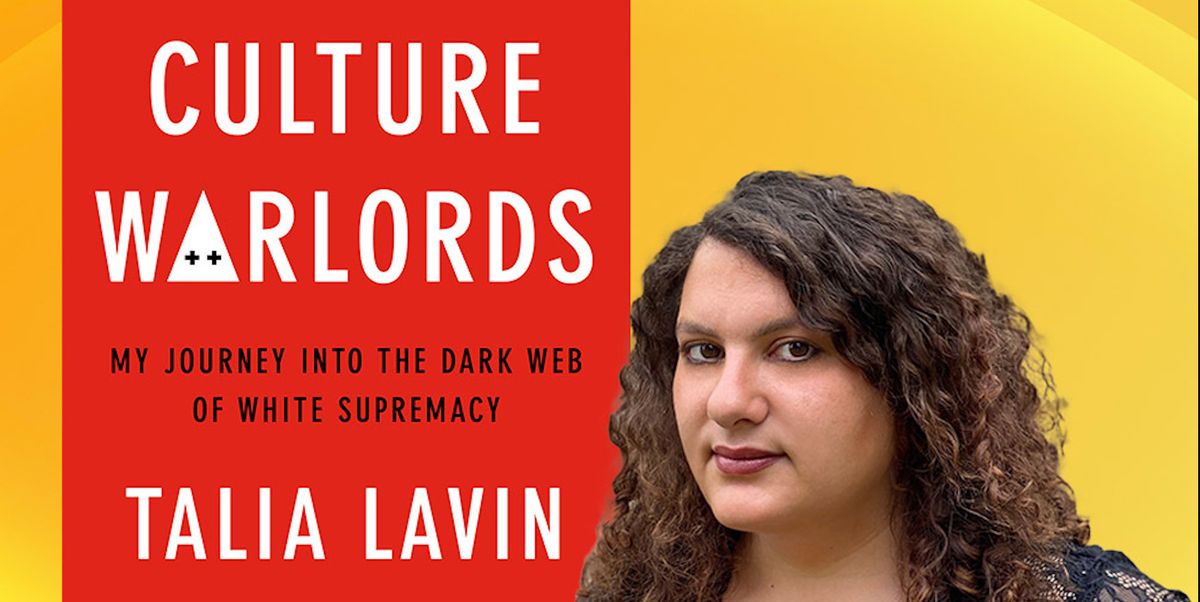

According to Donald Trump, in  Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

When I was seventeen years old, I took my first college science course, a summer class in astronomy for non-majors. The professor narrated his wild claims in an amused deadpan, calmly showing us how to reconstruct the life cycle of stars, and how to estimate the age of the universe. This course was at the University of Iowa, and I imagine that the professor was accustomed to intermittent resistance from students like me, whose rural, religious upbringing led them—led me—to challenge his claims. Yet I often found myself at a loss. The professor used a soft sell, and his claims seemed somewhere beyond the realm of mere politics or belief. Sure, I could spot a few gaps in his vision (he batted away my psychoanalytic interpretation of the Big Bang by saying he had never heard of Freud), but I envied him. I wished that my own positions were so easy to defend.

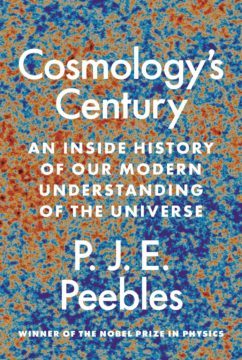

When I was seventeen years old, I took my first college science course, a summer class in astronomy for non-majors. The professor narrated his wild claims in an amused deadpan, calmly showing us how to reconstruct the life cycle of stars, and how to estimate the age of the universe. This course was at the University of Iowa, and I imagine that the professor was accustomed to intermittent resistance from students like me, whose rural, religious upbringing led them—led me—to challenge his claims. Yet I often found myself at a loss. The professor used a soft sell, and his claims seemed somewhere beyond the realm of mere politics or belief. Sure, I could spot a few gaps in his vision (he batted away my psychoanalytic interpretation of the Big Bang by saying he had never heard of Freud), but I envied him. I wished that my own positions were so easy to defend. Cosmology is a young science. Maybe the youngest. Some people say it started in the 1920’s when these little glowing clouds visible at certain points in the sky were found, by better and better telescopes, to be composed of billions and billions of stars, just like our own galaxy – the Milky Way – and it was then discovered that no matter what direction you looked they were all rushing away from us. More than one cosmologist has wondered if these galaxies know something that you and I don’t.

Cosmology is a young science. Maybe the youngest. Some people say it started in the 1920’s when these little glowing clouds visible at certain points in the sky were found, by better and better telescopes, to be composed of billions and billions of stars, just like our own galaxy – the Milky Way – and it was then discovered that no matter what direction you looked they were all rushing away from us. More than one cosmologist has wondered if these galaxies know something that you and I don’t.