by Philip Graham

Back in 1971, I couldn’t have predicted that the release of Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, Blue, would mark the beginning of the end of a friendship.

Back in 1971, I couldn’t have predicted that the release of Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, Blue, would mark the beginning of the end of a friendship.

During my college years, Donald and I had bonded over a love of literature and a shared ambition to become, some day, actual writers. While I chose the route of fiction, Donald wrote song lyrics, taking poetry classes to hone his craft.

The great songwriter love of his life was the Joni Mitchell of her first albums, Song to a Seagull, Clouds, and Ladies of the Canyon. But then Blue dropped, and it crushed Donald. He believed the new, conversational quality of Mitchell’s lyrics betrayed her past poetic strengths. While we sat in the college coffee shop he quoted a few lines from the song “California”:

So I bought me a ticket

I caught a plane to Spain

Went to a party down a red dirt road

and then protested with real hurt in his voice, “How could she write something so ordinary?”

I didn’t mind that Mitchell had moved away from her lyrical era of “mermaids live in colonies” and “sweet well water and pickling jars.” I thought she fully lived and breathed in her new songs, became more approachable as a fellow vulnerable human. Donald remained unmoved. I suggested that at least we still had her exquisite voice, her gift for melody, and her guitar playing—what haunted tunings!

He insisted he couldn’t listen to any song, no matter how beautiful, if he didn’t first respect the lyrics. I countered that no matter how well-composed a lyric, if the melody was a clunker I wouldn’t listen twice. The beauty of the music came first. If the words reflected that beauty? Bonus.

Donald made a sour face and said, “You want to be a writer, how can you say that?”

Annoyed, I made the mistake of adding that I would actually be hard-pressed to recite in full the words to any song, even my favorites—a confession I didn’t know was true until I’d spoken it. Too late to take it back. I could already see myself—and our friendship—shrinking in Donald’s eyes.

Later, while revisiting that conversation, I realized that my confession wasn’t entirely true. I wasn’t indifferent to lyrics, they simply weren’t the main reason why I listened to a song. All I needed to get the point of the Beatles’ “Eight Days a Week” was the song’s eponymous refrain—the remaining words served mainly as tuneful exegesis. But the ringing guitars and close vocal harmonies expressed something deeper. If a song’s lyrics were the equivalent of what one said aloud, then the music revealed a secret eloquence beneath those words.

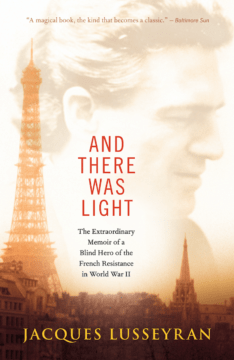

Perhaps this intuition about song craft explains why, many years later, a memoir by Jacques Lusseyran, And There Was Light, resonated so deeply within me. Lusseyran had been blinded in a school accident at the age of eight, and one might expect that his recounting of that fateful day and its aftermath would be filled with a certain amount of regret and bitterness. But he came to regard the accident as a great gift, one that opened him up to a sensory world that sighted people rarely experienced.

Perhaps this intuition about song craft explains why, many years later, a memoir by Jacques Lusseyran, And There Was Light, resonated so deeply within me. Lusseyran had been blinded in a school accident at the age of eight, and one might expect that his recounting of that fateful day and its aftermath would be filled with a certain amount of regret and bitterness. But he came to regard the accident as a great gift, one that opened him up to a sensory world that sighted people rarely experienced.

Soon after his blinding, Lusseyran discovered that people’s voices had become transparent to him. “I ended by reading so many things into voices without wanting to, without even thinking about it, that voices concerned me more than the words they spoke.” People revealed themselves unknowingly, because he heard not only their words but the music of their saying: “Our appetites, our humors, our secret vices, even our best guarded thoughts were translated into the sounds of our voices, into tones, inflections and rhythms.”

Because he could hear such telling music in speech, at the age of sixteen, Jacques Lusseyran became a valued member of the French resistance against the Nazi occupation of Paris. He’d sit in a corner, quietly attentive to whoever was being interviewed as a possible resistance recruit. If he liked what he heard in that person’s voice, heard a trustworthy landscape, then thumbs up.

*

Lusseyran’s revelation that voices are a complex music might explain why I listen to so much music from around the world: from Mali, Ethiopia, Sweden, Finland, Bulgaria, India, Madagascar, Algeria, even Uzbekistan. Throw me any country and I’ll catch it and listen to its music, perfectly fine with not understanding the language. For the all-encompassing genre labeled World Music, I often like to leave the lyrics to my own imagining. Especially when it comes to the song “Liyanzi Ekoti Ngai Ya Motema (Mouzi),” as performed by the great Congolese soukous musician Luambo Franco, and his Tout Puissant O.K. Jazz band.

In 1980, in the middle of my wife Alma Gottlieb’s anthropological research among the Beng people of Ivory Coast, she and I took a few day’s break from the village to celebrate our third wedding anniversary in Bouaké, the country’s second largest city. We wandered though outdoor markets, past skyscrapers and soccer fields, anywhere our curiosity led us. Once, while walking along the edge of a working-class neighborhood, we stopped at the sound of ringing guitars. A concert? Or a record playing much too loud?

In 1980, in the middle of my wife Alma Gottlieb’s anthropological research among the Beng people of Ivory Coast, she and I took a few day’s break from the village to celebrate our third wedding anniversary in Bouaké, the country’s second largest city. We wandered though outdoor markets, past skyscrapers and soccer fields, anywhere our curiosity led us. Once, while walking along the edge of a working-class neighborhood, we stopped at the sound of ringing guitars. A concert? Or a record playing much too loud?

The skittish, steady drums, the rhythmic tumble of guitars, the full-throated harmonies of the chorus, a horn section interjecting a kind of counterpoint, and the crest after crest of fluid musical drama drew us into the neighborhood’s alleys and the surprised looks of playing children, who gleefully followed such unexpected pale strangers.

On and on the song galloped, and Alma and I increased our pace, hoping to arrive before the song ended. Nearly lost in a maze of narrow streets, I remembered a time in college when I’d searched through the floors of a dormitory to find whoever was playing an equally infectious song (which turned out to be “Spain,” by Chick Corea’s band, Light as a Feather), and I wondered, Would this kind of chase become a continuing story in my life?

We finally arrived at a storefront that was little more than a tin-roofed wooden shack, though filled with hundreds of records on the walls, and more expensive stereo components than I’d ever seen in one place. This was our first encounter with bootleg record stores. Choose an album displayed on the wall, and in a couple of hours a taped copy would be yours for a reasonable fee.

The shop owner told us the song he’d been blasting was Luambo Franco’s “Liyanzi Ekoti Ngai Ya Motema (Mouzi).”

“What does that mean?” Alma asked.

He laughed. “Oh, I’m not from Zaire. I don’t understand Lingala.”

Luambo Franco, I later came to learn, was one of the greatest composers, guitarists and band leaders in modern West African history and perhaps the greatest proponent of soukous, a heady blend of African and Cuban musical styles.

Back in the village, I couldn’t stop playing that cassette tape. The song began at a fast clip, and the urgent voice of the lead singer (Ntesa Dalienst, the composer of the song) seemed to be reeling off some story. Then, by the three-minute mark, the song erupted into an ebullient and heartfelt emotion, the name of which I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Franco’s guitar playing shifted back and forth between intricate filigree and chiming, booming riffs, while the chorus and horns took their hearty turns. My favorite moment arrived just before the end, when a single voice sang out, “Yenowaaaaaaaay . . .” I had no idea what that word meant, but its delivery sounded like sweet longing.

What was this marvelous song about? It seemed to tell an epic tale, much like Chick Corea’s “Spain.” But singer Flora Purim’s vocals in “Spain” were wordless. Franco’s song was packed with words, and though in a language far from the linguistic mix of Ivory Coast, they were discoverable. I asked any number of people in the village and in the small nearby town of M’Bahiakro if they knew Lingala, but no one ever did. Zaire was over a thousand miles away.

Then came the day when I no longer wanted to understand the lyrics of my favorite song.

The reason? The musician Mamadou Doumbia. He sang in Dioula, which often served as a trade language in Ivory Coast, and many of our Beng friends and neighbors spoke it. His loping, relaxed brand of African country blues—perfect for sitting beneath the shade of a palm leaf awning on a sweltering day—was so popular that our tape player would barely get started when a neighbor or passing villager would comment approvingly, “Mamadou Doumbia!”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dn9vygHA2hc

What were his songs about? Perhaps some philosophical musings, an older man’s well-earned wisdom? One day, when Yacouba, our best friend in the village, dropped by, Alma and I asked if he’d translate some of Mamadou Doumbia’s lyrics.

Yacouba started with whatever song was already playing, though at first he hesitated. Chuckling nervously, he translated Mamadou Doumbia’s salacious appreciation of his favorite parts of a woman’s anatomy, starting at the top and working his way down to the toes. Not exactly the wisdom we’d been hoping for.

From that day on, I kept my curiosity about “Liyanzi Ekoti Ngai Ya Motema” to myself. No reason to ruin a good thing. Instead, I came up with my own stories for the song. Sometimes while listening I could imagine a view from the slope of a mountain, of distant storm clouds rushing toward miles and miles of still sunlit plain, where a herd of gazelles grazed and then, glancing up, raced for cover . . .

Or maybe the song sounded out the moment when the someone you’ve been avoiding out of fear and longing suddenly stands before you in the middle of a nightclub’s dance floor. Your hands meet, your silence is unspoken speaking, and then . . .

Or perhaps the song wasn’t a single dramatic moment but instead an entire reckless joyous life celebrated in one musical crescendo after another . . .

Slowly I created my own interpretive anthology of Luambo Franco’s song, which I would happily defend against any contradiction.

Only once was I tempted to give in to curiosity.

In 2003, our son Nathaniel, then a high school student, volunteered to help teach English to recently arrived immigrants. He was assigned to the children of a family that had fled the wars and political violence of Zaire. Early in the lessons, he noticed that his young students made unusual but consistent grammatical mistakes. Were they translating directly from their home language of Lingala into English? Nathaniel borrowed from one of Alma’s colleagues a Lingala dictionary and grammar to see if his hunch was correct. Sure enough, it was.

Occasionally I stared at that well-thumbed book on my son’s desk. How easily I might open it, pick out word by word the title of Luambo Franco’s song, and finally glean what fueled my favorite musical commotion. All I had to do was flip open that cover . . . .

But I never succumbed. The specter of Mamadou Doumbia always stood in the way.

Mamadou Doumbia! I had to let him go. Because was it really so reasonable to predict disenchantment whenever the meaning of a foreign lyric might be revealed? Wasn’t I limiting my appreciation of music I loved?

My opportunity for liberation arrived with the music of Susheela Raman. Born in London from Tamil parents from India, she began her career by fusing Western and Indian music. In “Mahima,”from her first album, Salt Rain, Raman added a bluesy bedrock to Carnatic classical music and created quite the sinuous, sexy slow burner.

I thought I understood the subject of the song, until one day I read that Mahima was actually a Vedantic prayer. This surprise at first threatened a Mamadou Doumbia-level of disappointment, but then gave way to admiration after I searched out the lyrics:

King of Kings

Live up to your name

As the embodiment of truth

Aren’t the great ones on the true path your devotees?

Don’t you shelter those

Driven to you by their own fecklessness

And release them from their misery?

Don’t be cruel to me

Just for your amusement

Knowing how much I need you

There it was, the sensuality of spiritual supplication. The effort of belief and doubt grappling with each other created an almost carnal intimacy that reminded me of John Donne, the greatest Metaphysical poet of the 17th century. In his younger years, Donne was most famous for his poem, “The Flea,” where he pimped a dead flea and spun a sacrilegious twist on the idea of the Trinity, all in the service of winning a reluctant lady’s tender graces. Eventually Donne found religion, and near the end of his life he served as the Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. He continued to write poetry, though the object of his affection was no longer a skeptical woman, but God. In his Holy Sonnet XIV he implores

There it was, the sensuality of spiritual supplication. The effort of belief and doubt grappling with each other created an almost carnal intimacy that reminded me of John Donne, the greatest Metaphysical poet of the 17th century. In his younger years, Donne was most famous for his poem, “The Flea,” where he pimped a dead flea and spun a sacrilegious twist on the idea of the Trinity, all in the service of winning a reluctant lady’s tender graces. Eventually Donne found religion, and near the end of his life he served as the Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. He continued to write poetry, though the object of his affection was no longer a skeptical woman, but God. In his Holy Sonnet XIV he implores

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

If you juiced up Donne’s sonnet with a broody backbeat, I’ll bet you’d get something close to Susheela Raman’s “Mahima.”

I now believe that trying to separate body and soul from a spiritual quest is as difficult as separating words from music in a song. You can enter the maze of a song through the words, or your chosen entrance might be the music. But you still share the same maze. And there may be as many mazes as there are songs.

Dog and Raven Coda

Though I’m still determined to forever keep the lyrics of Luambo Franco’s song as my personal mystery, I’m happy to enter music’s maze everywhere else. Sorten Muld, a “folktronica” band from Denmark, fuses a contemporary sound with traditional instruments, and it’s not unusual to hear a bagpipe or hurdy-gurdy in the electronic mix. Don’t let that spook you—this is elegant yet intense music. What will certainly spook you are their lyrics— ably sung by Ulla Bendixen—based on old Nordic folk tales. In one song, a father kills his daughter’s secret lover, and when he slices the heart into a meal that he serves his unknowing daughter, “never had she tasted a dish so delightful.” In another song, the bones and golden hair of a beautiful drowned woman are fashioned into a harp; when first played, that uncanny instrument sings a song of the woman’s murder and her jealous sister’s guilt.

“Ulver” may be my favorite Sorten Muld song. Handsome Ulver takes his lover Vaenelil on a journey, promising her “eternity.” At their first stop, Ulver settles into digging a grave, and Vaenelil asks,

For whom is this grave?

For your dog it is too long

For your horse it is too narrow.

Ulver replies,

The grave is for you, my greatest love

Eight virgins have I loved before

I have separated them all from this life.

Vaenelil calmly consents to prepare for the grave, but insists she first must comb her beautiful hair. Ulver agrees—a mistake, for her steady combing draws him into a deep sleep, and Vaenelil draws the sword from his arms and carves him up “for dog and raven.”

Like “Mahima,” Sorten Muld’s “Ulver” is undeniably enhanced when you embrace word and music. The inventive Techno sheen combined with ancient lyrics is the hidden point: the band’s modern music makes it impossible to relegate these gory tales to the past—we’re reminded that we, too, live in grim times.

Incantation Coda

Jacques Lusseyran’s vital role in the Parisian resistance is not the end of his story. Though his gatekeeper intuition about who to allow into his resistance cell had never failed for years, one time his decision was overruled, and that recruit ended up betraying Lusseyran and his fellow operatives to the Nazis.

They were all sent to Buchenwald where, remarkably, Lusseyran survived. How did a blind man successfully endure nearly two years in a concentration camp? Lusseyran tells us, in his extraordinary essay, “Poetry in Buchenwald.”

Because the prisoners hailed from all over Europe, life in the camp, aside from its usual daily terrors, was ruled by a profound isolation. “I knew that the first person I would bump into,” Lusseyran writes, “would not speak my language and would have none of my thoughts. And that for him I, in turn, would be an utter stranger.”

How to bridge this numbing isolation and somehow survive? Lusseyran chose to recite poetry, a personal ritual that taught him “poetry is an act, an incantation, a kiss of peace, a medicine. I learned that poetry is one of the rare, very rare things in the world which can prevail over cold and hatred.”

What began as a private tactic became a public offering. Lusseyran, who from an early age had discovered the complex music hidden in ordinary voices, chose for his recitations only the work of poets who possessed “the art of song.” He did this for a practical reason: there were so many languages in the camp, his reciting often had little to do with comprehension, so the actual words of the poems couldn’t be the point. But words that evoked music helped Lusseyran and his fellow prisoners endure together, if only for a while, their grim surroundings:

“I threw myself into a poetry campaign. In the middle of the block, at midday, I stood there and recited poems. I was the neighborhood singer and passers-by stopped. They pressed in around me. Soon other voices answered mine. I felt them all so close to my body that I could hear the in-and-out of their breath, the relaxation of their muscles. For several minutes there was harmony, there was almost happiness.”