by Michael Liss

November 6, 1860. Perhaps the worst day in James Buchanan’s political life. His fears, his sympathies and antipathies, the judgment of the public upon an entire career, all converge into a horrible realty. Abraham Lincoln, of the “Black Republican Party,” has been elected President of the United States.

November 6, 1860. Perhaps the worst day in James Buchanan’s political life. His fears, his sympathies and antipathies, the judgment of the public upon an entire career, all converge into a horrible realty. Abraham Lincoln, of the “Black Republican Party,” has been elected President of the United States.

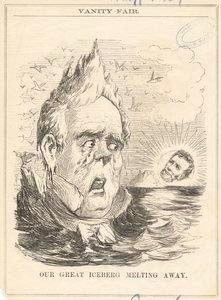

Into Buchanan’s hands falls the most treacherous transition any President has had to navigate. The country is about to split apart. For months, Southerners in Congress, in their State Houses, in newspapers ranging from the large-circulation influential dailies to small-town broadsheets, had been warning everyone who cared to listen that they would not abide an election result they felt was an existential threat to their Peculiar Institution. Lincoln, despite what we now consider to be his notably conservative approach to slavery, was that threat.

The task is made more excruciating because the transition, at that time, was longer—not the January 20th date we expect, but March 4th. Four long months until Lincoln’s Inauguration. Thirteen months between the end of the regular session of the outgoing Congress and the first scheduled session of the incoming one, unless the President calls for a Special Session. Each day, the speeches become more radical, the threats blunter. Committees are formed in many states to consider secession. By December 20, South Carolina leaves the Union. It is followed in short order by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and, on February 1, 1861, Texas. The Upper South (Tennessee, North Carolina, and all-important Virginia) holds back, as does Arkansas. Unionist sentiment is strong enough to keep them from bolting, but the cost of their loyalty is that nothing aggressive be done by Washington to bring back the seceding states. In reality, that means an acceptance of secession for those that cannot be wooed back.

Buchanan is not the man for the job. Read more »