by Adele A Wilby

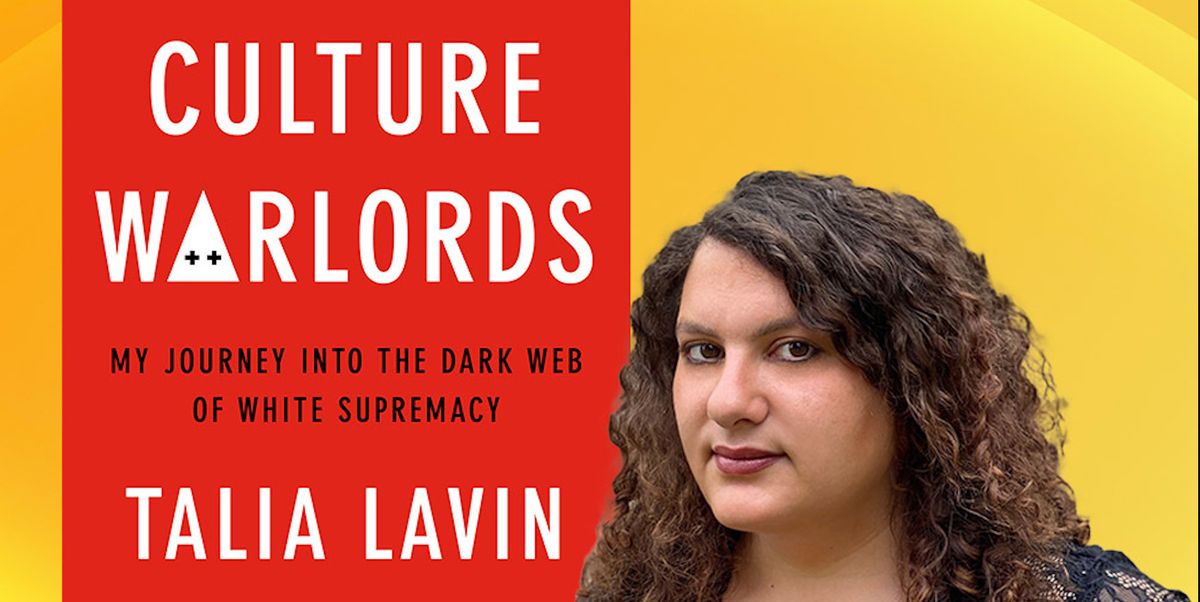

Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

Lavin opens her book with an explicit acknowledgement of her politics. She admits that she is ‘to the left of Medicare for All’. Thus, there is no pretence of ‘objectivity’ in the subject of her research and analysis: the book is an account of her one year internet engagement with a ‘sliver of a movement’ of the right-wing spectrum. Her research though adds up to a shocking yet thought provoking first-hand account of the thinking that underpins the deep hate and the almost godlike worship of violence that white supremacists profess.

However, it was not Lavin’s politics that took her down the path into the dark world of the internet web where far right fanatics find ‘camaraderie’, spewing out their myths and conspiracy theories and vile hatred about anyone that doesn’t have white skin, or isn’t a Christian. Instead, Lavin’s first direct confrontation with racism in the form of anti-Semitism when working as an editorial intern at the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, launched her journey down the path to research that gave birth to this book. In the first chapter, ‘On Hating’, an unpleasant subject in itself for any book, she sets out how she discovered anti-Semitism in its modern guise; it was ‘out of the Jackboot and behind the keyboard’. Her daily dealings moderating comments for the agency picked up a regular trafficker of anti-Semitic vitriol posted by Stormfront.org, a white supremacist website, the largest hub for neo-Nazis at that particular time. Understandably, the barrage of Nazi paraphernalia and descriptions of what the fascists wanted to do to Jews touched a nerve with Lavin, and she knew she had a battle on her hands, and she was ‘going to fight’.

But as many people are aware, ‘intelligence’ about the enemy is fundamental for fighting a battle, and after seeing that she herself was a target of the far-right following her publication of articles critical of fascists, Lavin determined to discover more about the pedlars of hate. She chose the weapon of disguise and assumed different personas as a way into the webpages where she could source the characters and thinking that lurked so threateningly, yet anonymously, amidst the maze of the internet web. The breadth of the aptitude for the politics of hate by far-right supporters is evidenced by the sheer numbers of webpage sites that support such views. By June 2019, Lavin had joined ninety far-right groups on ‘Telegram’, a plurality of English-language channels that could be accessed through ‘8chan’ thread as it was then, a webpage now notorious for its links to ‘QAnon’, the most recent and growing network of conspiracy theorists. ‘Procurement’, another webpage also lists far right channels in what seems to be an endless thread linking haters to one another. These websites have thousands of subscribers from all over the world.

Initially intending to be an observer of the right-wing rhetoric, the expressions of violence, the racial hatred and anti-Semitism exchanged between these fascists, Lavin finally assumed different personas with a view of engaging with subscribers to these web pages. The raw ‘intelligence’ Lavin gathered literally from the horse’s mouth, is deeply troubling and disturbing, not least for the most basic reason that the harbingers of such hatred are ‘just people, just like you and me’, ‘there are rich men and poor men, tradesmen and office workers, teenagers and men cresting middle age’ the difference being of course that their world vision is warped, ‘riven by terror, awash in the blood of those they consider subhuman. Which means anyone non-white; which means anybody Jewish; which means anyone who fights back their putrid ideology.’ Pathological souls spewed out their anti-Semitism, misogyny and white-supremacist rhetoric to Lavin under her various guises. She became Ashlynn, the ultimate fantasy of many a white male supremacist: ‘a petite blonde, slender, gun-toting woman who enjoyed hunting and grew up in a white nationalist family from Iowa’, a ‘real flesh-and-blood woman eager for seed’. There is of course irony here, and it is not missed on Lavin: imagine the horror of those right wing fanatics on the other end of the web should they have known that the ‘good Christian, conservative who despises diversity and Multiculturalism’, the woman who will ‘teach our kids to keep away from the darkies and to marry white people when they grow up’ was in fact their antithesis: ‘a schlubby, bisexual Jew…with long brown ratty curls, the matronly figure of a mother…’ as she describes herself.

Racist language however is not always enough to satisfy the hatred of some of these fascists; they need a visual feed of grisly images of inhuman violence against the targets of their hate. Gruesome images are displayed in webpages to subscribers and then a process of desensitising the viewer to shocking violence and dehumanising the victim is set in process. Indeed, as Lavin discovered, an all-out race war is the dream of these white supremacists on web pages such as ‘Terrorwave’, ‘Hans Right Wind Terror Centre’ and ‘Vet War’. Many of these subscribers advocate the’philosophy of far-right accelerationism’ – a ‘philosophy’ that argues that white-supremacist revolution is only possible through violence and the best time for that violence is now. It should not come as any surprise therefore that the white supremacist mass murderers, the Norwegian Andres Behring Brevik, and the Australian Brenton Tarrant have become iconic figures for many of those evil advocates of a race war.

An interesting aspect of Lavin’s research is the way in which many men start off with misogyny and end up as fascists. To understand this link between misogyny and white supremacy a persona change for Lavin was necessary, and she became the woman hating man, Thomas O’Hara, an incel, an ‘involuntarily celibate’ a euphemism for male virgins. Such a condition could quite easily evoke sympathy for people in those circumstances, and one cannot help being curious as to why in this wonder world of sexual opportunity these men find themselves in such involuntary circumstances. In reality these virgin men on the websites are just a truly pathetic group of people who are literally driven mad by their sexual frustration. The misogyny creeps in however, when rather than seeking out reasons and solutions to their sexual frustration they opt to blame ‘cruel’ women who deprive them of sex. Instead, these inadequate men swear to take revenge against women, and women have lost their lives as a result. With a deep hatred of women, ‘women are careless, heartless whores’, coupled with a good dose of self-pity and self-hatred, incels lose any empathy they might have had for others and are sucked into other hatreds as a threatened group on the fringes of society. Thus, the link between white supremacist and misogynists is established, with both sharing and feeding each other’s hatred of others with the web as the conduit of connection.

The world wide web is a boon to white supremacists and connects those in Eastern Europe, Western Europe, Australia, and the United States. According to Lavin, it also facilitates the transfer of money, tactical coordination and even personnel. Indeed, Lavin discovers that white supremacists from the United States have trained with the Ukrainian far-right militia that forms part of the country’s national guard, a frightening prospect given the ‘philosophy’ of accelerationism that figures so largely in the rhetoric of white supremacists. Ashlynn’s character returns at this point as Lavin delves into the world of the Ukrainian far right to learn more about these web activists. She re-evokes the persona of Ashlynn and uses the screen name ‘Aryan Queen’ to lure David ‘the most violent racist’ online with a view of coaxing out more personal information about him. We learn that David draws his inspiration from Australian mass murderer Breton Tarrant’s ‘manifesto’. He is just twenty-two years old, full of venom for others. Lavin plays him at his game and after five months he dishes out enough personal details to secure his identity, enough ‘intelligence’ for Lavin’s ‘fight’ against fascists. She passes the information to a journalist who exposes David, a far-right winger with the potential to commit mass murder: she has outed a Nazi.

The outing of any Nazi has to be hailed as an achievement, and Lavin has to be applauded for her commitment to expose these nefarious characters, but there are more of them out there, more than is known, anonymous, lurking on the fringes, churning out and circulating their hate filled messages and images, and preparing for the start of their race war. She herself got a glimpse of their potential danger when she rather naively spent a day at Minds IRL Conference to ‘research in person’ a conference for right-wing You Tubers and their supporters. Her tweets from the conference riled some participants and when she refused to delete them, she hot footed out of the conference just in time to avoid the fury of Jeanesca, a female participant at the event and the crowd that gathered around her.

However, another dangerous aspect associated with the far right is it increasing appeal to children. More recently, the Metropolitan Police in London expressed concern over the increasing right-wing radicalisation of young people between the ages of 12-18 years during the lockdown period. Between August 3 and August 22, 2019 no fewer than seven white-nationalist shootings were prevented by the relevant authorities. Thus, in her concluding chapters Lavin sets out her views on countering fascist propaganda and activism, and she gives significance to the much maligned Antifa, an organisation to which Trump apportions blame for the anti-racist protests that have become a feature of American society.

Lavin has to be admired for her bravery and endurance in spending one year ‘living in the bowels of hate’ in her determination to expose to the reader what hate actually looks like and how the internet works to support it. It took its toll on her mental health: she spent some time in the ‘grip of depression’ while writing this book. But as a measure of the more subtle impact of far-right extremism on the lives of people, Lavin says the experience has ‘taught me how to hate’, an entirely rational understanding in response to a realisation that the target of much of the right-wing hatred includes those she loves so dearly. For that reason, she has become part of the story of the impact of how such despicable hatred and glorification of violence by extreme right-wing fanatics impacts on the individual. However, arguably it is not so much that she has learned to hate that is the issue, but rather, she knows how and to whom she should focus her love, and that, as her anti-fascist activism tells us, extends well beyond her family.