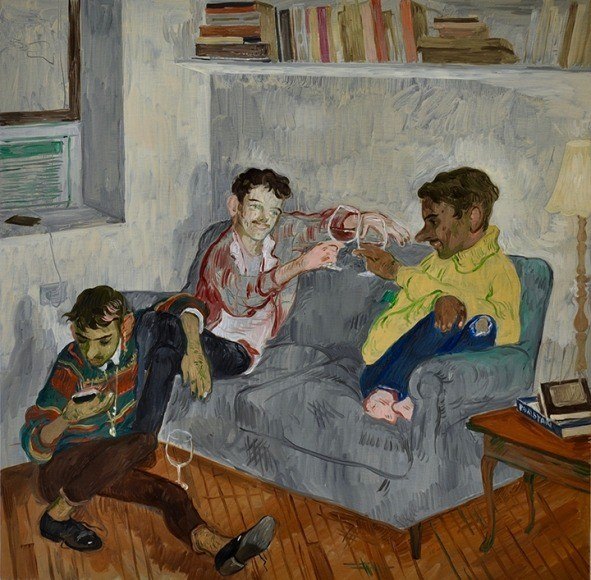

Salman Toor. Three Friends. 2018.

Oil on panel.

by Usha Alexander

[This is the sixth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

“The American way of life is not up for negotiation.” —George HW Bush to the assembled international diplomats at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, 1992

“The American way of life is not up for negotiation.” —George HW Bush to the assembled international diplomats at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, 1992

“Much talk. Talking will win you nothing. All the same, the woman goes with me to the house of Hades.” —Thanatos to Apollo in a scene from Alcestis by Euripides, 5th Century, BCE

***

In Classical Greek mythology, Thanatos was Death. As a minor god who got little press in the surviving tales, he appears in the play, Alcestis, as something of a functionary, dutifully gathering those whose time had come and spiriting them to the underworld. Not that he doesn’t find some satisfaction in his work, but he wields his power neither masterfully nor hungrily. The touch of Thanatos did not bring on death from war or violence—those deaths were the domain of other deities—but an ordinary death, as experienced by most. In ancient times, Thanatos was often depicted as a winged youth, as a babe in the arms of his mother, Nyx, goddess of Night, or with his twin, Hypnos, Sleep. Thanatos was not a villain. But he was ruthlessly inevitable.

In the 21st Century Marvel film franchise, Thanatos has been reinvented as Thanos. In this reimagining, Thanos still wields death, but he sees his job in larger terms: he wants to bring peace to the universe, which is engulfed in strife. “Too many mouths. Not enough to go around,” he explains, referring to the overpopulation of the Marvel Universe. Thanos’s solution is to reduce the number of living things through a painless existential cleanse that will magically drift across the universe, gently annihilating half of everybody. He understands himself as the only being possessed of both will and power enough to act upon the need of the hour—to turn every other being into dust, thus restoring balance and enabling peace among the untold trillions who will survive. His desire to erase half of all the living isn’t personal, nor is it inspired by cruelty, venality, or a lust for power. Like his Greek inspiration, Thanos is pragmatic, goal-oriented, and transactional. Though he’s depicted with the stature of a supervillain, in command of limitless legions of grotesque warriors, he’s motivated by a sense of duty: the universe is out of balance and must be set right. “I am inevitable,” he quietly declares. Read more »

by Eric J. Weiner

Ours, like the moments after the Civil War and Reconstruction and after the civil rights movement, requires a different kind of thinking, a different kind of resiliency, or else we succumb to madness or resignation. —Eddie S. Glaude Jr.

Those convictions and motives, upon which the Nazi regime drew, no longer belong to a past that one can count by the intervening years: they have returned with the radical wing of the AfD – up to and including its phraseology – to the democratic everyday. —Jürgen Habermas: Germany’s Second Chance

Not since the Civil War and Reconstruction has the citizenry in the United States been so divided. In our current historical conjuncture, the division can be characterized as a fight between Trumpism and “the Resistance.” As a political bloc and in its current formation, the Resistance is comprised of too many fractured groups to have a coherent ideological agenda. The one thing that these disparate groups can agree on is their fury and disdain for Trumpism and the people who support its white-nationalistic, xenophobic, misogynistic, anti-democratic, neoliberal agenda. It’s clear what and who they are fighting against but less clear what they are collectively fighting for. In contrast to the Resistance, Trumpism is a fully realized neofascist ideology with a cult-like following that won’t go away with Trump. It is a principled system that directs and solidifies a disparate constituency with differential attachments yet not at the expense of ideological cohesion and coherence. As this battle rages on in the United States, the democratic experiment teeters on the brink of failure. The election of Joe Biden to the presidency does not end the threat that neofascism represents to democracy in the United States. But it might provide an opportunity to systematically formalize critical educational strategies that can help re-enculturate a divided citizenry into a radically democratic habitus.

Not since the Civil War and Reconstruction has the citizenry in the United States been so divided. In our current historical conjuncture, the division can be characterized as a fight between Trumpism and “the Resistance.” As a political bloc and in its current formation, the Resistance is comprised of too many fractured groups to have a coherent ideological agenda. The one thing that these disparate groups can agree on is their fury and disdain for Trumpism and the people who support its white-nationalistic, xenophobic, misogynistic, anti-democratic, neoliberal agenda. It’s clear what and who they are fighting against but less clear what they are collectively fighting for. In contrast to the Resistance, Trumpism is a fully realized neofascist ideology with a cult-like following that won’t go away with Trump. It is a principled system that directs and solidifies a disparate constituency with differential attachments yet not at the expense of ideological cohesion and coherence. As this battle rages on in the United States, the democratic experiment teeters on the brink of failure. The election of Joe Biden to the presidency does not end the threat that neofascism represents to democracy in the United States. But it might provide an opportunity to systematically formalize critical educational strategies that can help re-enculturate a divided citizenry into a radically democratic habitus.

I know using the term neofascism to describe something other than formal state systems of uberviolence is provocative and controversial. Yet, according to Brad Evans, Chair in Political Violence & Aesthetics at the University of Bath in the United Kingdom and Henry Giroux, McMaster University Chair for Scholarship in the Public Interest & The Paulo Freire Distinguished Scholar in Critical Pedagogy, there are fourteen political principles of neofascism that articulate with our current historical conjuncture even as they acknowledge that the lived reality of this new form of fascism that is germinating in the United States is substantively different from its 20th century European and South American versions.[1] If we ignore how these political principles of neofascism are undermining the democratic habitus, we are engaging in a form of “historical amnesia” and might miss, as a consequence, an opportunity to develop anti-neofascist/pro-democracy educational projects that can help reverse the rise of its popularity in the United States. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Michael Liss

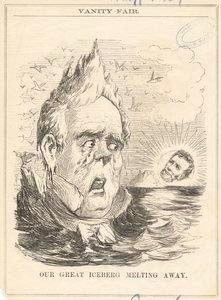

November 6, 1860. Perhaps the worst day in James Buchanan’s political life. His fears, his sympathies and antipathies, the judgment of the public upon an entire career, all converge into a horrible realty. Abraham Lincoln, of the “Black Republican Party,” has been elected President of the United States.

November 6, 1860. Perhaps the worst day in James Buchanan’s political life. His fears, his sympathies and antipathies, the judgment of the public upon an entire career, all converge into a horrible realty. Abraham Lincoln, of the “Black Republican Party,” has been elected President of the United States.

Into Buchanan’s hands falls the most treacherous transition any President has had to navigate. The country is about to split apart. For months, Southerners in Congress, in their State Houses, in newspapers ranging from the large-circulation influential dailies to small-town broadsheets, had been warning everyone who cared to listen that they would not abide an election result they felt was an existential threat to their Peculiar Institution. Lincoln, despite what we now consider to be his notably conservative approach to slavery, was that threat.

The task is made more excruciating because the transition, at that time, was longer—not the January 20th date we expect, but March 4th. Four long months until Lincoln’s Inauguration. Thirteen months between the end of the regular session of the outgoing Congress and the first scheduled session of the incoming one, unless the President calls for a Special Session. Each day, the speeches become more radical, the threats blunter. Committees are formed in many states to consider secession. By December 20, South Carolina leaves the Union. It is followed in short order by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and, on February 1, 1861, Texas. The Upper South (Tennessee, North Carolina, and all-important Virginia) holds back, as does Arkansas. Unionist sentiment is strong enough to keep them from bolting, but the cost of their loyalty is that nothing aggressive be done by Washington to bring back the seceding states. In reality, that means an acceptance of secession for those that cannot be wooed back.

Buchanan is not the man for the job. Read more »

by Bill Murray

This column is about travel to less understood parts of the world. In yet another travel constrained month, how about a little political tourism here in Georgia, where none of us really understands the sordid late-Trump morality play swirling around our dual Senate runoffs. We still have thirty days to go. Unlikely circumstance offered our state the fate of the Senate and we are shaky stewards.

Beware pundits bearing wisdom. All their elaborate, self-assured opinions at this early stage tell me that when the national press comes to your town with instant, penetrating analysis of, say, Flint’s municipal water supply, or that crazy Sturgis biker thing, be careful. They bring to mind Emerson’s “the louder he talked of his honor, the faster we counted our spoons.”

All punditry has right now is conventional wisdom. Here on the actual battlefield, candidates compete against one another, the Republican party competes against itself, dark money scurries in the shadows, QAnon jeers from the sidelines and the truth is, nobody has any idea what’s going to happen. Read more »

by Philip Graham

Back in 1971, I couldn’t have predicted that the release of Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, Blue, would mark the beginning of the end of a friendship.

Back in 1971, I couldn’t have predicted that the release of Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, Blue, would mark the beginning of the end of a friendship.

During my college years, Donald and I had bonded over a love of literature and a shared ambition to become, some day, actual writers. While I chose the route of fiction, Donald wrote song lyrics, taking poetry classes to hone his craft.

The great songwriter love of his life was the Joni Mitchell of her first albums, Song to a Seagull, Clouds, and Ladies of the Canyon. But then Blue dropped, and it crushed Donald. He believed the new, conversational quality of Mitchell’s lyrics betrayed her past poetic strengths. While we sat in the college coffee shop he quoted a few lines from the song “California”:

So I bought me a ticket

I caught a plane to Spain

Went to a party down a red dirt road

and then protested with real hurt in his voice, “How could she write something so ordinary?”

I didn’t mind that Mitchell had moved away from her lyrical era of “mermaids live in colonies” and “sweet well water and pickling jars.” I thought she fully lived and breathed in her new songs, became more approachable as a fellow vulnerable human. Donald remained unmoved. I suggested that at least we still had her exquisite voice, her gift for melody, and her guitar playing—what haunted tunings!

He insisted he couldn’t listen to any song, no matter how beautiful, if he didn’t first respect the lyrics. I countered that no matter how well-composed a lyric, if the melody was a clunker I wouldn’t listen twice. The beauty of the music came first. If the words reflected that beauty? Bonus. Read more »

by Bill Benzon

A little over a week ago Jacob Collier’s version of Mel Torme’s “The Christmas Song” (“Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire”) came up on YouTube. I know the song well, and love it. As I’d seen a video or three by this Collier fellow, I decided to give it a listen.

Wow! What?

I was stunned, but also a bit skeptical. Collier was obviously a talented musician, with mad skills. But to what end? This struck me as being musical comfort food. Skillfully made – oh yes! the man has chops! – but comfortable. But then, what’s wrong with comfort? As a steady aesthetic diet, it’s inadequate. But don’t we sometimes turn to music for comfort and solace? Do we not need comfort and solace in this time of Covid, not to mention the post-election tantrums of He Who Must Not Be Named?

What else has Collier got? If it’s all like this, then Collier’s a one trick pony. But maybe he’s got more tricks up his sleeve. I decided to investigate.

Caveat: I’m going to insert a bunch of videos into this piece; one of them is very long – over three hours. Feel free to skip over material. Read more »

by Dave Maier

2020 has been a wild ride, but it’s almost over, and I’m here to tell you it wasn’t all bad, as some great music came out this year – so much, in fact, that we’ll have to have two or even three podcasts this time even for the small taste which is our annual year-end review. Here’s part 1 (widget and link below).

2020 has been a wild ride, but it’s almost over, and I’m here to tell you it wasn’t all bad, as some great music came out this year – so much, in fact, that we’ll have to have two or even three podcasts this time even for the small taste which is our annual year-end review. Here’s part 1 (widget and link below).

Jonathan Fitoussi – Soleil de Minuit

We heard a great track from this guy in a recent set, and here he is again with a terrific new album of unashamedly retro space music. “Soleil de Minuit” (“Midnight Sun”), for example, performed on a Buchla modular system, electric organ, and electric bass, sends off a distinctly Michael Hoenig vibe to my ear. Keep ‘em coming, Jonathan, we love it. Read more »

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Before the COVID pandemic, travel to academic conferences and colloquia was a large part of the job of being a professor at a research-focused university. The last few months have given us the opportunity to reflect on the hurly burly of academic travel. We’ve keenly missed many things about those in-person events. Yet there were things we don’t miss very much at all. While academic conferences are still paused, we wanted to make a note about what’s worth our time and not, and then make some resolutions about what we can do better.

The bloom of online conferences since last Spring provides a key point of comparison. The online conference has many of the same problems that beset the in-person conference: the schedules are overfull with interesting papers at conflicting times, presenters go over their allotted times and thereby leave no time for discussion, and the Q&A sessions tend to go off the rails with people asking questions that have more to do with their own views than with the presentation. But we were still pleased that the move online allowed younger scholars the opportunity to shine and get uptake with their work. And we were able still to hear a few presentations that provided some real insight. In these respects, online conferences are much like their in-person counterparts.

But there are differences. A unique feature of in-person conferences lies in the unplanned sociality that they make possible. The in-person setting allows for the possibility of passing some luminary in the hall between sessions, or meeting someone whose work you just read. In fact, it’s a piece of unacknowledged common wisdom that the true value of in-person conferences lies in unstructured time when one is not attending sessions. Read more »

by Ali Minai

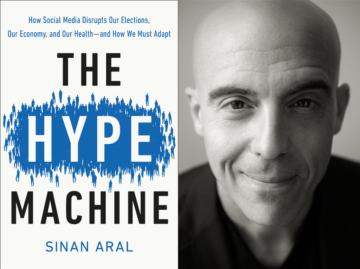

Given where we find ourselves in this late November of 2020, it is hard to think of a book more relevant or timely than The Hype Machine by Sinan Aral. The author is the David Austin Professor of Management and Professor of Information Technology and Marketing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As one of the world’s foremost experts on social media and its effects, Prof. Aral is the perfect person to look at how this phenomenon has changed the world and the human experience. This is what he sets out to do in his new book, The Hype Machine, published under the Currency Imprint of Random House this September, and with considerable success.

Given where we find ourselves in this late November of 2020, it is hard to think of a book more relevant or timely than The Hype Machine by Sinan Aral. The author is the David Austin Professor of Management and Professor of Information Technology and Marketing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As one of the world’s foremost experts on social media and its effects, Prof. Aral is the perfect person to look at how this phenomenon has changed the world and the human experience. This is what he sets out to do in his new book, The Hype Machine, published under the Currency Imprint of Random House this September, and with considerable success.

The book provides an excellent overview of where things stand with social media, its promise and its peril. For anyone looking for a single, accessibly non-technical source of information and insight on these important issues, this book is essential reading. The book is very well-organized, and the logical flow – both across and within chapters – is remarkably smooth. Overall, the book is an easy read that informs and educates the reader without getting mired in technical jargon – no mean feat for a book about a technical field that is rife with jargon. And, while a large proportion of the book simply communicates information on where things stand and how different social media platforms are shaping the lives of their users, Prof. Aral does not shy away from building a useful abstract framework in which to place all this, and to address the complex issues raised as a result. Read more »

Dylan Kwait. Surfers by Plum Island, October 2020.

Dylan Kwait. Surfers by Plum Island, October 2020.

Drone photograph.

With permission … thanks Dylan!

by Claire Chambers

This has been a terrible year with almost no redeeming features. I have written elsewhere about Covid-19’s hardships, both personal and political. Today, with a vaccine on the horizon and Trump defeated, I want to find some other crumbs of comfort that, as with Hansel and Gretel, might take us somewhere.

I am privileged to live with my husband Rob and two sons in our own house with a garden, and to hold down a lecturing job which is pretty secure. Rob is even more financially stable in his career, working as he does in a growth industry this pestilent year: he’s a family doctor.

But of course being a GP has brought its own share of unexpected stresses recently. In March when the UK government spectacularly failed to get PPE for medical professionals and disaster capitalists were circling, Rob bought some pyjamas from Marks and Spencer for turning into improvised surgical scrubs. He even fashioned his own visor using a piece of sponge, some plexiglass, and a coat hanger. Although he never had to use it, I won’t forget that time of helpless, abandoned terror.

Nigerian-American author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie posted a microblog to Instagram early into this crisis about her fears around the pandemic. When I read these terse words, I nodded vigorously:

My husband is a doctor and each morning when he leaves for work, I worry. My throat itches and I worry. On Facetime I watch my elderly parents. I admonish them gently: Don’t let people come to the house. Don’t read the rubbish news on WhatsApp.

Out of the two vulnerable parents Adichie was worrying about in this essay from April, it is poignant to realize that her father was to die just two months later. Read more »

by Chris Horner

Not long ago there was an article circulating on Facebook about ‘Hating the English’, originally published in a large circulation newspaper. The Irish author says something to the effect that once she thought it was just a few bad ones etc., but now she hates the lot of them. It’s been stimulated, I think, by the repulsive English nationalism that has been raising its head since Brexit, plus the usual ignorance about Ireland, Irish history and Irish interests on the part of your typical ‘Brit’. It’s not a very good piece of writing, and it has a rather slight idea in it. I’d ignore it but for the ‘likes’ and positive comments it’s received, particularly from ‘leftists’. It’s an example of what we could call ‘bloc thinking’ – the emotionally satisfying but futile consignment of entire masses of people into categories of nice and nasty.

Not long ago there was an article circulating on Facebook about ‘Hating the English’, originally published in a large circulation newspaper. The Irish author says something to the effect that once she thought it was just a few bad ones etc., but now she hates the lot of them. It’s been stimulated, I think, by the repulsive English nationalism that has been raising its head since Brexit, plus the usual ignorance about Ireland, Irish history and Irish interests on the part of your typical ‘Brit’. It’s not a very good piece of writing, and it has a rather slight idea in it. I’d ignore it but for the ‘likes’ and positive comments it’s received, particularly from ‘leftists’. It’s an example of what we could call ‘bloc thinking’ – the emotionally satisfying but futile consignment of entire masses of people into categories of nice and nasty.

It has a number of obvious problems. It is deeply unwise to brand entire national groups good or bad, to declare love or hate for whole ethnic or national communities. Too many English people have branded the Irish in just that way throughout their shared and troubled history; just repeating it the other way is hardly progress. This kind of thing is the habit of the worst kinds of right wing chauvinists, and we should steer well clear of it. We get the same kind of thing about, for instance, from ‘anti-imperialists’ despising the ‘Americans’ (meaning usually: ’citizens of the USA’). This is particularly obtuse when it comes from people who have never visited the USA and don’t know anyone who lives there. Just think: 328 million people, rich and poor, white, black or brown, anglo and latino, from coast to coast. All dismissed, because policies emanating from ‘America’s’ ruling 1%. It is true that many – not all by any means – US citizens will have supported those policies, but that ought to be the beginning of a problem to think about, not the invitation to simple minded moralising. Fatuous generalisations are so obviously foolish that it might not detain us long, if it were not for the tendency of this kind of approach to encompass whole swathes of people, demographics and even generations as Good or Bad. So we get Greedy ‘boomers’ versus ‘millennials’, or whatever crass label is currently in use. And so on. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Thomas Larson

According to Donald Trump, in a statement made to MSNBC’s “Morning Joe,” April 11, 2011, about the fake “birther controversy” of President Barack Obama—the opening salvo in Trump’s campaign of political disinformation—Obama’s “grandmother in Kenya said, ‘Oh, no, he was born in Kenya and I was there and I witnessed the birth.’ She’s on tape,” Trump went on. “I think that tape’s going to be produced fairly soon. Somebody is coming out with a book in two weeks, it will be very interesting.”

According to Donald Trump, in a statement made to MSNBC’s “Morning Joe,” April 11, 2011, about the fake “birther controversy” of President Barack Obama—the opening salvo in Trump’s campaign of political disinformation—Obama’s “grandmother in Kenya said, ‘Oh, no, he was born in Kenya and I was there and I witnessed the birth.’ She’s on tape,” Trump went on. “I think that tape’s going to be produced fairly soon. Somebody is coming out with a book in two weeks, it will be very interesting.”

And, according to Vox News, President Trump, two weeks after losing the 2020 November 3rd election, tweeted, “I won the election!” He had warned many times prior to the vote that the only way he would lose the election would be if it was rigged, and the only way he would win was if the election was fair, a remarkably trenchant conjuration of the Three Witches’ spell on Macbeth, “Fair is foul, and foul is fair.”

And, according to Chanel Dion of One America News and Trump legal team lawyer, Sydney Powell, software engineers in Michigan and Georgia (and in parts of 26 other states) contracted with Dominion Voting Systems, which has financial ties to Nancy Pelosi, Dianne Feinstein, George Soros, the Clinton Foundation, and the seven-years-dead Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, to make ballot-counting machines switch votes from Republican to Democrat presidential candidates or to leave out a prescribed number of votes for President Trump in Joe Biden’s favor. Read more »

by Adele A Wilby

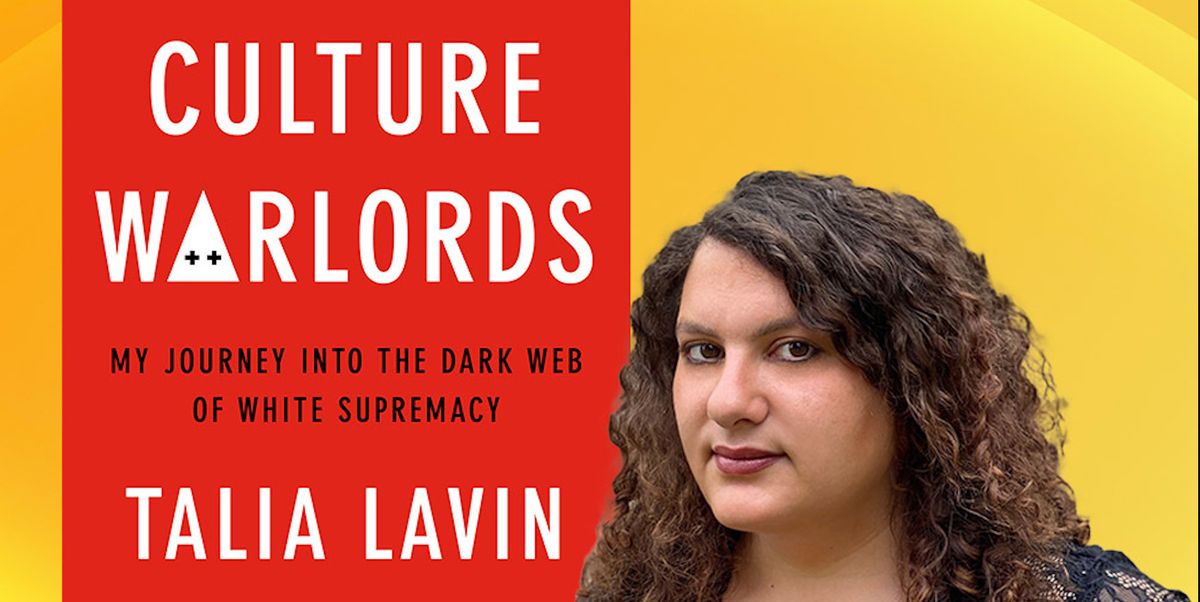

Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

Lavin opens her book with an explicit acknowledgement of her politics. She admits that she is ‘to the left of Medicare for All’. Thus, there is no pretence of ‘objectivity’ in the subject of her research and analysis: the book is an account of her one year internet engagement with a ‘sliver of a movement’ of the right-wing spectrum. Her research though adds up to a shocking yet thought provoking first-hand account of the thinking that underpins the deep hate and the almost godlike worship of violence that white supremacists profess. Read more »

by David Kordahl

When I was seventeen years old, I took my first college science course, a summer class in astronomy for non-majors. The professor narrated his wild claims in an amused deadpan, calmly showing us how to reconstruct the life cycle of stars, and how to estimate the age of the universe. This course was at the University of Iowa, and I imagine that the professor was accustomed to intermittent resistance from students like me, whose rural, religious upbringing led them—led me—to challenge his claims. Yet I often found myself at a loss. The professor used a soft sell, and his claims seemed somewhere beyond the realm of mere politics or belief. Sure, I could spot a few gaps in his vision (he batted away my psychoanalytic interpretation of the Big Bang by saying he had never heard of Freud), but I envied him. I wished that my own positions were so easy to defend.

When I was seventeen years old, I took my first college science course, a summer class in astronomy for non-majors. The professor narrated his wild claims in an amused deadpan, calmly showing us how to reconstruct the life cycle of stars, and how to estimate the age of the universe. This course was at the University of Iowa, and I imagine that the professor was accustomed to intermittent resistance from students like me, whose rural, religious upbringing led them—led me—to challenge his claims. Yet I often found myself at a loss. The professor used a soft sell, and his claims seemed somewhere beyond the realm of mere politics or belief. Sure, I could spot a few gaps in his vision (he batted away my psychoanalytic interpretation of the Big Bang by saying he had never heard of Freud), but I envied him. I wished that my own positions were so easy to defend.

Seventeen years later, I’m now in the professor’s position, defending physics to doubting undergraduates. My views now are mostly easy to defend. Yet as someone who never progressed much beyond an undergrad knowledge of astronomy (I took one graduate cosmology course and left it at that), I’ll admit that some of the things that bothered me back then still bother me today. Some of the grandest claims in physics are based almost solely on astrophysical evidence, including the assertion that our standard physics accounts for less than 5% of what’s really there, with the other 95+% of mass-energy in the woolly categories of “dark energy” and “dark matter.” Such views are mainstream enough now to invite few scientific naysayers. Read more »