by Mary Hrovat

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.”

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.”

My family went to the public library every two weeks, and there were books in the house, so I was given at best a mixed message about reading. I seized the opportunities offered by the books around me while evading the imposed limits. I read in the closet in the evening after my sister was asleep, or in the living room late at night when everyone was asleep. When I could, I read while I ate. Perhaps I was fortunate to have a boundary to transgress, ever so gently and passively, so as to avoid being entirely subsumed in the role of good girl.

I was reading to learn, but also to escape. Reading for escape is sometimes seen as an inappropriate use of time or a failure to accept reality. Look what happened to Emma Bovary and Catherine Morland (characters created by Gustave Flaubert and Jane Austen, respectively), who came to grief (in very different ways) by taking novels far too seriously. But escape from boredom, emotional distress, or anxiety is no bad thing. I tend to agree with W. Somerset Maugham, who said that reading provides “a refuge from almost all the miseries of life.” I was lucky this refuge was available to me. The power to escape into a book was a rare means of control over my circumstances, and I can’t imagine what life would have been like without it. Read more »

Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

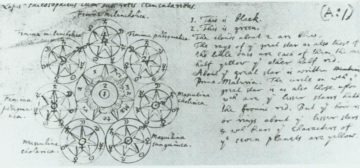

Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class is a famous, influential, and rather peculiar book. Veblen (1857 – 1929) was a progressive-minded scholar who wrote about economics, social institutions, and culture. The Theory of the Leisure Class, which appeared in 1899, was the first of ten books that he published during his lifetime. It is the original source of the expression “conspicuous consumption,” was once required reading on many graduate syllabi, and parts of it are still regularly anthologized.

Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class is a famous, influential, and rather peculiar book. Veblen (1857 – 1929) was a progressive-minded scholar who wrote about economics, social institutions, and culture. The Theory of the Leisure Class, which appeared in 1899, was the first of ten books that he published during his lifetime. It is the original source of the expression “conspicuous consumption,” was once required reading on many graduate syllabi, and parts of it are still regularly anthologized.

Last month

Last month  My Jewish maternal grandparents came to America just ahead of WWII. Nearly all of my grandmother’s extended family were wiped out in the Holocaust. Much of my grandfather’s extended family had previously emigrated to Palestine.

My Jewish maternal grandparents came to America just ahead of WWII. Nearly all of my grandmother’s extended family were wiped out in the Holocaust. Much of my grandfather’s extended family had previously emigrated to Palestine.