by Emrys Westacott

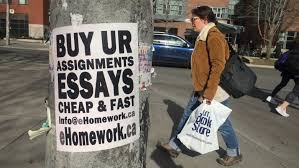

Academic dishonesty is a widespread problem in colleges in many countries, and it is getting worse. One particular form of cheating has become especially common in the age of the internet: students buying custom-written essays–a.k.a. “contract cheating.” A recent study estimated that over 15% of college students had paid someone else to do their work for them;[1]and given that this figure is based on self-reported dishonesty, the true figure is quite likely to be higher.

Academic dishonesty is a widespread problem in colleges in many countries, and it is getting worse. One particular form of cheating has become especially common in the age of the internet: students buying custom-written essays–a.k.a. “contract cheating.” A recent study estimated that over 15% of college students had paid someone else to do their work for them;[1]and given that this figure is based on self-reported dishonesty, the true figure is quite likely to be higher.

Back in the day, plagiarism would typically consist of a student copying out some passages from an obscure source, or perhaps from a fellow student’s essay. This approach involved a certain amount of work. Pre cut-and-paste, you had to actually copy out chunks of text. Pre the norm of typed essays, you’d even do this longhand. There was a serious danger that you might learn something in the process. But the method had two obvious advantages. It was free. And there was little chance of getting caught.

The internet left traditional plagiarism in the dust, along with hardcopy journals and encyclopedia salesmen. Cutting and pasting passages found online was child’s play. Unfortunately, anything easily found by a plagiarist could be just as easily found by a professor. Worse, plagiarism-detecting software like Turnitin could expose even cunningly stitched together passages drawn from multiple sources.

But when one door closes, another one opens. Demand for custom-written college essays surged. These are essays that are usually written by decently educated, experienced writers, many with advanced degrees, often living in countries where writing other people’s essays is the most lucrative work they can get.

The essays are tailored to specific assignments and will not appear anywhere else on the web, being sent directly to the customer. The obvious drawback to this form of plagiarism (apart from the fact that the plagiarist doesn’t learn anything) is that it can be quite expensive: $20 per page is at the low end.

If you want to get a quick sense of how extensive the problem is, simply google “buy college essay.” There appear to be hundreds of sites offering high quality, risk-free essays guaranteed to be delivered on time. Although they trade in dishonesty, these sites are disarmingly honest about what they assume to be their client’s motives. Here’s a typical enticement:

“Why do you have to waste those precious days of youth on tedious and tiresome academic paper writing? You can take the easier, smarter path! Buy a college essay online! It is a more convenient way to get rid of the stressful situations associated with academic life.”

So what is a college instructor to do. The best short-term response is probably to devise assignments and forms of assessment that make cheating difficult. One possibility, for instance, is to have students submit outlines and drafts of any essay they turn in. But this adds to the workload of instructors who may already be grading hundreds of essays each semester. Another option is to have students write in-class essays, give oral presentations, create videos or podcasts, and so on. The problem here is that while such assignments may push students to learn some material and develop certain skills, they aren’t so great for helping students understand and master the writing process. And that, after all, is one of the important functions of the traditional college essay.

The fundamental problem, though, is not short-term. What is the fundamental problem? Some will argue that it has to do with a decline in moral standards. More students cheat today, they will say, because the rising generations care less about values such as honesty or fairness. Possibly, although I have my doubts about this. It’s certainly hard to verify. Moreover, students today find themselves in very different circumstances than their forebears. The cultural environment is more competitive. The consequences of failure are greater, since many more people now graduate from college. And the opportunities–a.k.a. the temptations–to cheat are more readily available. Who knows how previous generations would have behaved in this sort of environment.

In my view, the deeper problem has to do with the way education is increasingly viewed by students in purely instrumental terms–that is, as a means to an end, the end being a diploma, which is in turn viewed simply a means to the end of getting a certain kind of job. Those that look on their education in this way are less likely to concern themselves with how well, or even with whether, they have actually learned something. They are even less likely to be interested in pedagogical ideals such as a well-rounded education, cultural literacy, critical thinking, or an enlarged mind.

But students don’t arrive at an instrumentalist view of education by themselves. In this, they are aided and abetted by parents, school teachers, employers, politicians, and, sad to say, college faculty and administrators. It is part of the cultural atmosphere that we all inhale these days, reflected in the league table approach to judging schools and colleges, in the tables reporting average incomes of graduates from various colleges or in specific disciplines, and in the shrinking–in some cases the elimination–of departments in the arts and humanities.

To be clear, preparing people to work in various professions has always been one of the important purposes of education. That in itself is not the problem. There is nothing wrong with vocational training–although I do think there is something wrong with viewing a university education as vocational training and nothing else besides. But at present, colleges are increasingly regarded by many of their customers as diploma mills; and, inevitably, since the paying customer can never be completely wrong, this is how colleges start to see themselves, even if they don’t quite admit it. The instrumentalist attitude is thus reinforced; and the diploma mills spawn a rising demand essay mills.

It is obviously unrealistic to expect a sudden sea change in attitudes among those inclined to cheat. An outbreak of idealism regarding the aims of education is no more likely than a sudden upsurge in moral idealism that would put the essay mills out of business. In the long term, though, I honestly do believe that a renewal of a certain kind of idealism is needed, and is, ultimately, the best way to reduce contract cheating and any other form of academic dishonesty.

The idealism in question is the kind that holds fast to a view propounded by Plato and Aristotle: that education should benefit the whole person for their whole life. Someone who believes this obviously has less incentive to cheat since they would be depriving themselves of the benefit being aimed at. They would be like someone who goes to the gym to get fit but manipulates the treadmill counter to make it look as if they’ve worked out more than they actually have. And to be fair, many students today do see their education in this light. The problem is not that such idealism is dead but that it seems to be declining.

Idealists are always open to the charge that they are naive, that people’s living conditions and social environment shape their attitudes, not vice versa. To this there is the obvious retort that attitudes and ideals can and sometimes do have causal efficacy–witness the recent legalization of gay marriage in many countries. And there is also the hope that sometimes empirical reality will cooperate in making some ideals more attractive and realizable. Regarding education, for instance, it is conceivable that if automation reduces the amount of time people spend working, the idea of education as preparing us, among other things, to use our leisure in fulfilling ways will once again come into its own.

[1]Phillip Newton, “How common is commercial contract cheating in higher education and is it increasing? A systematic review” Frontiers in Education, Aug. 30, 2018. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2018.00067/full