by Brooks Riley

Now that the Emmys are over and we Americans have patted ourselves and a few Brits on the back for outstanding work, it’s time to consider one of the grandest achievements of the past year, a Netflix series from South Korea called Mr. Sunshine, which has, inexplicably, been ignored by media critics in the West.

Now that the Emmys are over and we Americans have patted ourselves and a few Brits on the back for outstanding work, it’s time to consider one of the grandest achievements of the past year, a Netflix series from South Korea called Mr. Sunshine, which has, inexplicably, been ignored by media critics in the West.

Masterpiece Theater meets Gone with the Wind seems a sorry way to try to pigeonhole this epic series and there are those who might want to relegate it to the level of soap opera in costume. Mr. Sunshine is operatic, yes, but there’s not a soap bubble in sight in this multi-faceted, extravagant, scrupulously constructed tale of Korea at the turn of the last century.

I had planned a different essay this time, a critical examination of Nietzsche’s writings on Richard Wagner and was deep into reading and researching for that post when I started Mr. Sunshine. At first, I was able to divide my days between the loquacious, bellicose Mr. N in the morning, and the reticent finesse of a sprawling word-spare historical drama from the Far East at night. As time went on, however, I was lured away from Nietzsche’s late-19th-century twitterstorm, moving deeper into a subtly structured saga set in the Korea of a few years later–its rich, intricate dramaturgy, its attention to detail, its sprawling story, its inspired screenplay. Nietzsche’s infantile trolling of Wagner and counterpunch extolling of Bizet paled against the quiet retributions, political intrigues and slowly unfurling love quadrangle within a roiling cultural and social upheaval on the other side of the globe.

Binge-watching a series is like boarding a ship of fools. For days on end, the viewer is a prisoner at sea inside a narrative vessel carrying specimens of humanity who are blindly hurtling toward their respective destinies, as we are made privy to unfamiliar narratives, people and places. Netflix has made it possible to travel beyond our shores and safe expectancies, providing series from all over the world, each with its own brand of story-telling that may acknowledge Hollywood but doesn’t bow down to it. (If Netflix doesn’t cure xenophobia, nothing can.) I’ve watched many fine examples, from Europe, Israel, South America, Australia and the US. The better ones, such as Shtisl (Israel) Mystery Road (Australia)or Black Spot (France/Belgium) offer alternative real worlds to lose oneself in as an embedded voyeur, without having to resort to the made-up worlds of fantasy or science fiction. Mr. Sunshine is the first such series I’ve seen from the Far East.

It’s one thing to produce a historical epic like Gone with the Wind, encapsulating a brief period of history on a grand scale while filtering it through the many small dramas that give flesh to a moment in time—all within a few short hours. Hollywood knows how to do this—or used to know. It’s quite another to produce a 30-hour, breathtaking epic series on a modest budget (only $35 million), one that trumps the old Civil Warhorse in many inconceivable ways.

It’s one thing to produce a historical epic like Gone with the Wind, encapsulating a brief period of history on a grand scale while filtering it through the many small dramas that give flesh to a moment in time—all within a few short hours. Hollywood knows how to do this—or used to know. It’s quite another to produce a 30-hour, breathtaking epic series on a modest budget (only $35 million), one that trumps the old Civil Warhorse in many inconceivable ways.

At the core of its brilliance is a master storyteller, the remarkable Eun-sook Kim, a screenwriting legend in Korea, with many hit series behind her. This dramaturgy queen is uniquely qualified to weave a story out of improbable threads and make it shine with emotion, meaning, tragedy and dramatic intricacy. Qualified, yes, but I’m not sure anyone could have predicted such a superb result. Although her series are hits in Korea, their genres have been quite different from this one, which falls into the category of sageuk, movies or series that mine the history and/or mythology of Korea.

To avoid stepping into a spoiler minefield, a short premise: Eugene Choi, the Korean child of runaway slaves, escapes to America and returns to the Kingdom of Joseon (Korea) as an American soldier and consul on the cusp of significant historical change, when the newly independent kingdom, freed from centuries of Chinese Qing domination, is struggling to resist Japanese aggression against its fragile independence. Choi’s bitterness and ill intentions against the land of his birth fester beneath a calm exterior, until he meets a woman from the noble class, the class he holds responsible for the violent deaths of his parents.

To avoid stepping into a spoiler minefield, a short premise: Eugene Choi, the Korean child of runaway slaves, escapes to America and returns to the Kingdom of Joseon (Korea) as an American soldier and consul on the cusp of significant historical change, when the newly independent kingdom, freed from centuries of Chinese Qing domination, is struggling to resist Japanese aggression against its fragile independence. Choi’s bitterness and ill intentions against the land of his birth fester beneath a calm exterior, until he meets a woman from the noble class, the class he holds responsible for the violent deaths of his parents.

After a melodramatic first episode of backstories dating to 1871, the ‘present’ of the series settles down. It is 1902: Nietzsche has been dead for two years and unavailable for comment much longer than that. The hermit kingdom of Joseon is waking up to a gold rush of colonial powers looking to exploit its resources—Russia, the United States, China, and especially Japan, to whom it matters most. Centuries-old social traditions are changing as well: Slavery has been abolished, a middle-class is emerging, and Western wear and customs are leaching into the hermetic society as foreigners arrive bearing their vices along with their virtues.

At the heart of this populous sweep of a tale is a love story. Most historical films rely on such a hook to lure the viewer back down to the human level of history. And nothing says ‘love’ quite like natural-born enemies. Think Romeo and Juliette. Think Tristan und Isolde.

But wait, hadn’t I left Nietzsche and Wagner behind? Not quite. As the episodes rolled by, I began to recognize what I call the Tristan effect, that intense yearning that goes on forever without ever reaching a climax. Wagner achieved this effect with music, building his romantic theme and leitmotifs to a fever pitch which seems to be leading inexorably to a final chord of consummation, but never arrives and is, in fact, brutally cut off at just the moment we expect to be bathing at last in ecstasy.

Mr. Sunshine’s love story, between the young Korean American consul Eugene Choi and the aristocratic rebel Ae-shin Go follows the same path, moving relentlessly and exquisitely toward a union, only to be foiled each time by the intervention of facts, fate or fatalism. Maintaining romantic tension over 24 episodes requires a meticulous manipulation of plot and dialogue, something Kim manages to do in surprisingly inventive ways.

Mr. Sunshine’s love story, between the young Korean American consul Eugene Choi and the aristocratic rebel Ae-shin Go follows the same path, moving relentlessly and exquisitely toward a union, only to be foiled each time by the intervention of facts, fate or fatalism. Maintaining romantic tension over 24 episodes requires a meticulous manipulation of plot and dialogue, something Kim manages to do in surprisingly inventive ways.

In today’s Western world where romance has been reduced to flirting-with-then- falling-into-bed with someone, the polite bonding rituals here might seem old-fashioned. But this is 1902: Different rules apply, and restraint is in order. We are given the chance to become reacquainted with the courtships of yore, the realms of Jane Austen, or even Kar-Wai Wong’s In the Mood for Love. The dialogue is spare, the silences vast, the euphemisms copious as we strain to read between the lines or listen to the silences. Eun-sook Kim’s elliptical dialogue is so refined, so suggestive, so sensitively filigreed, that Austen’s dialogue between Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth seems crudely literal by comparison. As we lean into the sweet nothings and somethings of intense romantic communication between two might-be lovers, the hormone oxytocin fairly oozes from the pixels on the screen as we find ourselves falling in love again—with falling in love.

The dialogue, paced in short phrases with silences wedged between them, exerts an almost hypnotic effect. It’s a way of conversing which owes much to nunchi, a unique Korean form of communication that has been described as “the subtle art and ability to listen and gauge others’ moods.” Nunchi, translated literally as ‘eye measure’, explains the verbally choreographed interlocutions between characters in Mr. Sunshine. Koreans ‘read’ people as they speak with them, adjusting their conversation and pauses to take into account whatever they intuit of the other person’s frame of mind. (Having lived in foreign cultures as a child and an adult, I recognize that need to ‘read’ the people I meet, as well as understand their language.)

Screenwriter Kim offers a sly send-up of nunchi in the confrontation between Choi and the villain Wan-ik Lee, who has just boasted of killing innocent farmers:

Choi: You son of a bitch!

Lee: What?

Choi: Ahhh. Being an American, I must’ve spoken my mind.

Here in the West, we do speak our mind. If something needs saying, we do so without hesitation, often without nuance and most often without consideration for the listener. We might leave room for a retort, but rarely for the lasting impact of our words—the meaningful silences. Hollywood romance reaches its zenith with ‘I love you.’ Or ‘I’m sorry.’ Repeatedly. Our screenwriters—and our society too—have lost the imagination and patience to slowly unwrap the package that is love, despite the richness of the language available to us.

Nunchi is also at the heart of the acting, forcing a Western viewer to strive for the same sensitivity to mood and emotion as a Korean audience might have, to read a face for the clues to be found in a slight movement of the eyes, the head or a corner of the lips. Byung-Hun Lee as Eugene Choi delivers a riveting performance full of contradictions and inner conflicts that slowly emerge, as from a fog, on the smooth landscape of his face. He is able to move seamlessly between the American part of his character (with a nearly flawless accent) and the Korean. His acting is a master class in subtlety. Even against the splendid work of Tai-ri Kim as the iron-willed porcelain lady Ae-shin, whose own nunchi-inspired performance offers another reading challenge, it’s difficult to take one’s eyes off him. The quiet intensity of his character makes those rare outbursts of rage and grief even more effective. His eyes seem to have a vocabulary all their own, while his voice, a deep whisper, conjures the chills associated with ASMR, or “autonomous sensory meridian response” which has gone viral as a sensual effect to offset the noise of our modern lives. (There’s a fair amount of other ASMR effects in the series, from the brushing sound of a silk hem moving over the back of a hand, to the enhanced whoosh of a hat being blown off the head, the rising volume of a ticking watch, the impossible echo of footsteps.)

Nunchi is also at the heart of the acting, forcing a Western viewer to strive for the same sensitivity to mood and emotion as a Korean audience might have, to read a face for the clues to be found in a slight movement of the eyes, the head or a corner of the lips. Byung-Hun Lee as Eugene Choi delivers a riveting performance full of contradictions and inner conflicts that slowly emerge, as from a fog, on the smooth landscape of his face. He is able to move seamlessly between the American part of his character (with a nearly flawless accent) and the Korean. His acting is a master class in subtlety. Even against the splendid work of Tai-ri Kim as the iron-willed porcelain lady Ae-shin, whose own nunchi-inspired performance offers another reading challenge, it’s difficult to take one’s eyes off him. The quiet intensity of his character makes those rare outbursts of rage and grief even more effective. His eyes seem to have a vocabulary all their own, while his voice, a deep whisper, conjures the chills associated with ASMR, or “autonomous sensory meridian response” which has gone viral as a sensual effect to offset the noise of our modern lives. (There’s a fair amount of other ASMR effects in the series, from the brushing sound of a silk hem moving over the back of a hand, to the enhanced whoosh of a hat being blown off the head, the rising volume of a ticking watch, the impossible echo of footsteps.)

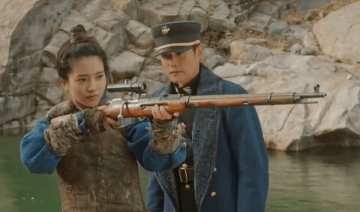

Byung-Hun Lee and Tai-ri Kim are not the only fine actors at the core of the series: Yohan Byun as the ne’er-do-well fiancé slowly develops a conscience, maturing in stature and emotional gravitas along the way. Min-Jung Kim as the duplicitous widow who owns the Glory Hotel maneuvers exquisitely over the treacherous terrain of her character and adds a fetching scrunch of the eyes to punctuate her charms. Seung-Joon Lee as the beneficent but ineffectual King of Joseon, Moo-Seong Choi as the gunner who teaches Ae-shin how to shoot, Kap-su Kim as the beer-swilling master potter and leader of the underground Righteous Army and Yeon-Seok Yoo as the Korean-born Japanese gangster who harbors a hopeless passion for Ae-shin. Few of these actors will ever become household names in the West, but their talents compare favorably with many iconic Hollywood performers.

Nietzsche may have left the building, but Wagner is still around in the form of the leitmotifs that screenwriter Kim harvests from a vivid imagination. Where Wagner provides them musically, Kim relies on words, phrases, concepts and material objects which she manipulates throughout the series to provide a variety of meanings, and differing levels of significance: Moving forward-stepping back, side by side, that look, trembling, bitter/sweet, ill intentions, sad ending among the phrases; shoes, daisies, flame, blackbird (Götterdämmerung’s raven?), watches, time, music box, sea, coffee, study, mountain, Russian doll, to name more than a few.

Using ‘language barrier’ as a recurring trope, Kim at one point extracts the word ‘love’ (or low-vuh in a Korean accent) and delivers it to Ae-shin’s character as a foreign word whose meaning she has not yet learned, only to have Choi break it down into components—introduction, handshake, hug, longing (Wagner again)—for the clueless Ae-shin who mistakenly thinks that the word ‘love’ refers to some worthy philanthropic project. It’s a charming sequence, full of gentle humor. It’s also unabashedly romantic and relies on the Tristan effect to prolong the suspense over several episodes. But what comes after ‘longing’? ‘Fishing.’ (Kim also knows when to put on the brakes.)

Great screenwriters are born, not made. The genius of Eun-sook Kim goes far beyond the realm of romance and dialogue. A master of irony and paradox, she eschews the clichés we’ve come to expect from high-end drama and replaces them with uniquely structured scenes that unfold with an almost musical precision and multi-layered ramifications that are never predictable, always fresh and original. She has a full grasp of narrative structure and character development—and she knows how to make a plot fold back on itself again and again. She could be tagged a Korean Julian Fellowes (Downton Abbey), but she’s much better than that.

In the end, a screenplay is only as good as its culmination on the screen. The young director Eung-Bok Lee provides his own bag of visual devices to bring Eun-sook Kim’s tour-de-force to life (the two have collaborated before). With a rare facility for maneuvering both grand-scale action and hothouse intimacy, he applies a highly sensitive mise-en-scène to the quiet moments between two or three characters, piling on close-up details and tracking shots that appear and disappear so quickly, we can’t be sure we’ve seen them. He tilts the frame sideways to comment on unresolved conflicts and introduces brief moments of slow motion to emphasize a point in the shot that matters but might be missed. His visual vocabulary is extensive, and always arresting, without calling too much attention to itself. Where he triumphs, however, is the direction of actors—clearly on the same wavelength as Kim and able to transform her highly structured scenes and dialogue (with asides) into natural consequence.

***

If there’s a deal-breaker in my unqualified affection for this series, it lies in the use of incongruous, slapstick humor at the periphery of the story. I first noticed this tendency in the Hong Kong martial arts epics of Tsui Hark in the Nineties and Aughts: An otherwise straightforward dramatic mood is suddenly interrupted by parody shtick from minor players, as though the viewer needed a comic olio to break the tension. What’s surprising about its appearance in Mr. Sunshine is that there is plenty of gentle humor that emerges organically from the main story, without having to inject screwball comedy at the edges. It is especially problematic when the parents of Ae-shin’s fiancé Hee-Sung Kim are introduced as overwrought parodies of aristocratic idiots, only to have to turn serious when Eugene Choi confronts them with their family’s crime. For a Western viewer unfamiliar with the oddities of comedy use in Asian films, the best way to get through these moments is to grimace and bear it.

My other caveat concerns soundtrack songs. I have an aversion to the use of songs within a film—a lamentable trend worldwide these days, one that catapults me immediately out of the mood: Lyrics are a spell-breaker, the words as intrusive as an uninvited dinner guest. The good news here is that most of the songs are in Korean, which becomes like another musical instrument to the foreign ear—and some are lovely. The bad news is that there are simply too many of them, threatening discreetly staged sequences with mawkish overkill.

The symphonic soundtrack, on the other hand, is splendid, written by the young composer Hye-Seung Nam. She certainly knows her classical repertoire (Bach, Dvorak, Debussy, Chopin, Rachmaninoff, Mozart, Bruckner, R. Strauss and of course Wagner) and delivers an astonishing variety of glorious symphonic moments as well as haunting, sensitive themes that underscore the narrative without compromising the scene’s dramatic integrity. She also sets a few of Eun-sook Kim’s leitmotifs to music, allowing their emotional implications to become familiar territory.

***

After weeks at sea on the flagship Netflix, I find myself back on dry land, in the present, home again from total immersion in a faraway land and time. Nietzsche (him again) once complained that Wagner’s “unending melody” forces one out to sea. I’d like to tweet back: What’s wrong with that?