by Ruchira Paul

Coming full circle from a medieval myth to present day reality – through a path strewn with storms, fires, snakes, spiders, dolphins, falling masonry, refugee ships, ghosts and goddesses

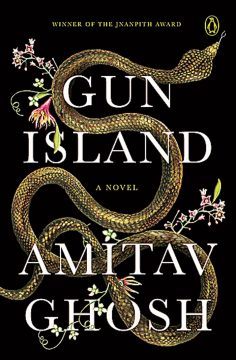

Following in the footsteps of the brilliant and exhaustive account of the British opium wars in his hefty Ibis Trilogy, Amitav Ghosh’s latest book Gun Island at just over 300 pages, is a relatively slim volume in which he returns to the Sundarbans to pick up from where his 2004 novel The Hungry Tide left off, with a dire warning about the ravaged ecological plight of the region. Only this time, Ghosh’s novel takes us out of the Sundarbans to Venice via Brooklyn, Kolkata and Los Angeles.

Following in the footsteps of the brilliant and exhaustive account of the British opium wars in his hefty Ibis Trilogy, Amitav Ghosh’s latest book Gun Island at just over 300 pages, is a relatively slim volume in which he returns to the Sundarbans to pick up from where his 2004 novel The Hungry Tide left off, with a dire warning about the ravaged ecological plight of the region. Only this time, Ghosh’s novel takes us out of the Sundarbans to Venice via Brooklyn, Kolkata and Los Angeles.

Added to nature’s fury are now new problems caused by the displacement of people and animals due to loss of habitat and livelihood, increase in crime and proliferation of unregulated industries that poison the environment. The result is more hardship on land and an unprecedented devastation of the region’s aquatic life. Some of the characters that figured in the previous book reappear in Gun Island. They are older, discouraged and fed up with the escalating degradation of the economy and the environment of this beleaguered part of the world. The prospect of fighting for a good life in the Sundarbans appears bleak.

Below is an excerpt from my review of The Hungry Tide describing the Sundarbans and the age old battle between its inhabitants and Mother Nature.

The story unfolds in the Sundarbans, the ferocious untamed jungle country in the Gangetic peninsula which begins at the edge of West Bengal in eastern India and stretches across the southern parts of Bangladesh up to its border with Myanmar. The region consists of a vast archipelago on the Bay of Bengal which the author describes as the “ragged fringed edge” of Mother India’s sari. It is a place where nature is both beguilingly prolific and ruthlessly savage. The jungles are thick and teeming with flora and fauna, the former dominated by the hardy mangrove and the latter by the magnificent Royal Bengal tiger. The intricate canals of the Sundarbans with channels of salt and fresh water, support numerous aquatic creatures which include fish, crocodiles, crabs and snakes. It is also the home of the south Asian Irrawady dolphin – a rare species of river dolphins. The islands of the Sundarbans are regularly battered by floods and cyclones. The human inhabitants of the islands are poor and depend mostly on the river and the jungle for their livelihood because the land is not suitable for agriculture due to repeated flooding with salt water. And they live their precarious and meager lives with one eye on the ebb and flow of the tide and the other on the menacing clouds which signal that a storm is brewing.

Throughout history, natural geological and meteorological upheavals have caused mass migration (and sometimes extinction) of living beings on earth. More recently, with humans having learned to manipulate the earth’s resources for their own advantage and comfort, natural causes are no longer the only contributor to the displacement and disappearance of various species. Man-made enterprises like commerce, slavery, colonization, urbanization, war, famine, globalization, environmental pollution etc. too have for many centuries contributed to the migration of man, sometimes playing havoc with animal and plant life both on land and in water. Some of the changes can be traced to chains of events that were set in motion centuries ago. Others are of more recent vintage resulting from the explosion in technological advances.

Gun Island is a first person narrative by the novel’s main character, the mild mannered Dinanath Dutta aka Deen, a dealer of rare books who lives and makes his living in Brooklyn, NY. Deen’s placid middle aged life is mostly occupied by books, academic meetings, worrying about his finances and trips to the therapist to figure out why he can’t form a stable romantic relationship. Every winter Deen travels to his childhood home in Kolkata (where his parents had come as refugees from East Bengal after the partition of India) to avoid the bitter cold of North America. During one such visit to the city, he is thrown into a maelstrom of unexpected events that spiral out on a path that is both bewildering and at times terrifying. It begins with a visit to the Sundarbans at the request of a family member as also by Deen’s own scholarly interest in a 17th century shrine associated with an ancient Bengali folklore about a sea faring merchant known as Bandooki Saudagar (Gun Merchant) and his power struggle with Manasa Devi, the Hindu deity of snakes and venomous creatures. The scenario that unfolds from there is rife with accidents, coincidences, natural disasters, feverish dreams, eerie precognition and trips across the continents by the novel’s characters – some with official travel papers and others without. The main characters besides Deen that figure in the novel are a pair of teenage boys – Tipu and Rafi – both denizens of the Sundarbans, Piya Roy, an Indian American professor of marine biology (she was one of the principal figures in The Hungry Tide) and the flamboyant Giacinta Schiavon (Cinta to her friends), a celebrated scholar of the history of Venice and the Jewish Ghetto situated in its inner island.

Gun Island is an intricate tale about climate change, environmental devastation, commerce, human aspirations, ambitions and desperation narrated in the manner of a fairy tale crisscrossed by modern day realities. It is also about the connectedness of the world over centuries, between far apart places that language, art and folklore can unexpectedly reveal. Amitav Ghosh is an anthropologist and historian by training. His fiction deftly interweaves current affairs with little known events of the past. Gun Island is no exception. Ghosh knits together the mythical tale of a long ago fugitive merchant sailor from Bengal who was persecuted and pursued by a vengeful goddess across many seas, with the life stories of 21st century modern characters many of whom too are fleeing from dangers to their lives. The stories of the characters are believable even if some of their experiences challenge credulity. The most unconvincing portrayal of the novel’s many characters is that of Cinta who in all her worldly wisdom and scholarly erudition comes across as the least credible because of her unerring ability to tie up every loose end, locate every lost piece of a confounding puzzle, not just through her knowledge of history but occasionally by her uncanny talent for “seeing” and “hearing” things that no one else does. In that respect she comes across almost like a goddess with supernatural powers. In contrast the no-nonsense scientist Piya is much more convincing as a rational but compassionate person who recognizes the fragility of life on earth and despite her clinical mindset she is occasionally surprised by her own vulnerability. All of these people with different interests and concerns follow their separate routes across the globe to converge on the island of Venice where myth and reality merge amidst a spectacular burst of activity on land and sea.

I am not sure how many readers here are fans of Ghosh and how much interest will be generated about Gun Island by this review. I myself enjoyed the book but it doesn’t rate among the author’s top five by my reckoning. The book is littered with abundant historical minutiae that Ghosh’s novels always provide and which is a large part of why I find his books fascinating. Human migration through the ages, voluntary and involuntary, caused by the lure of commerce or by the disruption of lives due to environmental and political catastrophes is the central theme of Gun Island. Upon his arrival in Venice in search of the history behind the Gun Merchant’s legend, Bengali American Deen is surprised by the clamor of Bengali he hears all around him. It is the language of Bangladeshi vendors, construction workers, cooks and cleaners who have replaced the locals in businesses that prop up the slowly sinking infrastructure of the beautiful city and offer the “authentic” Venetian experience to the millions of tourists who throng the island. Upon enquiry he learns that most of the immigrants arrived from Bangladesh on rickety and dangerous refugee ships from Libya and Egypt or over land through India, Pakistan, Iran and Turkey, their journeys facilitated by ruthless smugglers of human cargo. Like the Gun Merchant who fled Bengal in the 17th century to escape the venomous wrath of a goddess, the young men from Asia and North Africa have come there to escape the poisonous political and economic conditions of their respective places of birth. While the swarthy medieval Indian merchant may have blended well in the Jewish Ghetto of Venice in his day, the newcomers stand out as dark skinned foreigners, targets of vicious abuse by right wing politicians and natives who see them as cultural misfits and economic invaders even as they do all the low paying hard labor that the local population is no longer interested in doing. (A similar situation exists at the southern border of the US.)

Two outstanding authors who forever changed the nature of South Asian literature written in English are Salman Rushdie and Amitav Ghosh. They made their debuts within a few years of each other in the last part of the 20th century. Thanks to the excellent American public libraries, I came across them soon after Shame by Rushdie and Circle of Reason by Ghosh came out and well before either was widely known in the literary world. I was hooked. I followed the two avidly for many years. I have read all of Ghosh’s novels as also many of his non-fiction books. Rushdie and Ghosh employ entirely different cadence and velocity in their writings but they share some common aspects in their style of storytelling. Each has a propensity to whip back and forth between the past and present, legends and reality, to find connections between seemingly disparate events that occur centuries apart, all the while twisting the tongues of English speaking readers through linguistic calisthenics. Both resort to a touch of magic when plain facts alone wouldn’t get your attention. If dire predictions about the state of the world communicated by scientists and scholars do not penetrate the public psyche, a fantasy tale about looming disasters may convey a more urgent message. The digressions, feverish dreams, improbable coincidences in the novels of Rushdie and Ghosh may seem like long winded shaggy dog yarns to some readers. But the serpentine narratives do always end by making a relevant point about the world and the human condition. Ghosh said in an interview, “I read a lot of science, especially climate science, but I don’t think science is the only way to understand reality. It doesn’t exhaust our knowledge of the world.” I guess art as public service has always been a useful tool.