by Dave Maier

A while back, when I lived in Philly, my housemates and I got into a memorable discussion. It probably started off innocently enough, with someone wondering what it would be worth to you to lose a limb or something. But since I was involved, the conversation soon got weird, and soon we were thinking of more and more involved and downright bizarre contracts. I’ve forgotten most of them, but I’ve thought up a few more since then.

When someone came up with a good one, we’d each say how much money it would take for us to agree to the deal. It soon became clear that there were forces pulling in opposite directions. On the one hand, you didn’t want to look like a wuss. I shouldn’t need a billion dollars to spend my life in a wheelchair; plenty of people do that out of necessity, with no financial compensation, and they live perfectly fulfilling lives. Such people might be pretty offended to learn that you’d need vast sums of money to put up with the horror of living like they do. Keeping the number down would help to show that you regard such a thing as only a minor inconvenience.

On the other hand, you didn’t want to look like some guy on a Japanese game show, making a fool of himself seemingly for the sole purpose of appearing on TV (or earning a nominal sum). If I’m going to change my life in any real way, I’m not going to do it for a pittance. Some things, we often say, are priceless, and it’s easy to think of things I wouldn’t agree to for any amount of money. But what about things which aren’t quite so uniquely valuable? Everyone’s got his price. Make it high enough and I’m listening. If you really want me to give up nuts, berries and legumes, or agree never to visit South America, surely nine figures can get that done.

At the extremes, it seems that ethical considerations can come into play.

If the price goes high enough, it seems that one might be ethically obliged to take the deal no matter what. Think of what you could do with ten billion dollars – fund all kinds of worthy charities, or simply give it away as you see fit. People’s lives could depend on that money, and what kind of self-absorbed, entitled jerk would turn it down because it would cramp his style to eat Brussels sprouts at every meal, or wear only bright red clothing? Even as it is, philosophers like Peter Singer think you are ethically obliged to live frugally and donate as much as possible to charity.

Let’s ignore the numbers, then, and turn to particular cases. I remember Tom had a good one: what if you had to travel only on foot? Naturally this means no overseas travel, ever; but even going from NYC down to Philly would be a logistical nightmare. In this case, I demanded enough money to hire a staff, to help arrange things should I want to travel: map out the route, arrange accommodations along the way – maybe a tent if we’re in the middle of nowhere, which would require security as well – things like that. As it turned out, I was roundly mocked for this common-sense requirement. (“A staff!” they said. “Well, excuse me!” they said. Hmmph.)

My suggestions, as I recall, were mostly things which might seem like minor inconveniences – especially in the context of the vast fortune one would receive in return – but which would surely grate after a while, even to the point of making you rue the day you made that devil’s bargain. Little things, like having to make a loud sniffing sound at least once every hour of your waking life. Most of the time that would be easy to do: just excuse yourself, go to the restroom and do it there. But it wouldn’t always be so easy, and it would drive people crazy (part of the deal is that you can’t explain it to anyone). Worst of all, I think, would be the constant nag of always having to think about it: planning ahead, or worrying about whether the hour will be upon me at a particularly inconvenient time (a romantic moment, say, or at the movies).

My suggestions, as I recall, were mostly things which might seem like minor inconveniences – especially in the context of the vast fortune one would receive in return – but which would surely grate after a while, even to the point of making you rue the day you made that devil’s bargain. Little things, like having to make a loud sniffing sound at least once every hour of your waking life. Most of the time that would be easy to do: just excuse yourself, go to the restroom and do it there. But it wouldn’t always be so easy, and it would drive people crazy (part of the deal is that you can’t explain it to anyone). Worst of all, I think, would be the constant nag of always having to think about it: planning ahead, or worrying about whether the hour will be upon me at a particularly inconvenient time (a romantic moment, say, or at the movies).

There are a lot of things which would be like this: tolerable to an extent if your social sphere allowed that sort of eccentricity, but even then there would be the odd unanticipated, uncomfortable moment. I don’t remember which of these I thought of at the time, but it’s definitely a fertile source of examples:

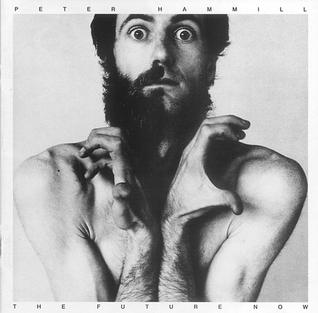

— having to shave off only the left half of your beard, and keep it that way

— having to greet everyone, always, with a loud, high-pitched “Helloooooooooo!”

— having to wear wayyy too much perfume/cologne

— having to correct every minor – or even debatable – grammatical error uttered in your presence, and having to study grammar books to be sure to catch them all (I have to say, this one will cost you)

My favorite suggestion was this: having to hold a potato in your left (or non-dominant) hand at all times. This makes an interesting contrast with (merely!) losing a limb. Your limb is in perfectly good shape, but it’s hard to use, and this comes up in all kinds of ways. (Again, too, you’re not allowed to explain it; you just have a potato in your hand all the time, that’s all.) Here too, as with the sniffing, life’s most precious moments – even if there are more of them, due to your wealth – will be in danger of being shot through with that element of ridiculousness, as notably lacking in the missing-limb cases. You take your newborn daughter into your arms for the first time, careful not to let the potato bonk her in the head. Everyone in the sky box at the World Cup final raises their arms in jubilation, but one of them has a potato in his hand, and can only high-five with the other hand. At the fancy dinner party, when I accept the serving platter from my neighbor, do I keep my hand in my lap, making the transfer difficult, or do the best I can with both hands? In either case my expensive clothing may start to feel too dearly bought.

The theme of enforced silliness can bring back into consideration our moral obligations to others. Maybe I can justify having people think me eccentric if it’s only my own life, but if others are involved, things look different. An example I thought of only recently (yes, my mind is a strange place) is this. In exchange for the riches of Croesus, you must name your first-born son “Crutbelg,” and your first-born daughter “Blaptod.” (A third child, or a second child of the same gender? Dutfleep. And so on.) Rest assured, every loophole has been anticipated. You may not put them up for adoption and then adopt other children with normal names. You may not use, or allow them to use, nicknames. You must refer to them by their names whenever you can, avoiding locutions like “my children” (“I can’t stay, Your Eminence, Crutbelg and Blaptod will be home any minute now.”) And, of course, you may not explain to anyone, even to them, why they have the names they do.

Morally, though, we might wonder whether it is fair to young Master Crutbelg to saddle him with such a moniker, even if it allows him (unbeknownst to him, remember) to live in the lap of luxury. At issue is not only his undoubtedly hellish childhood, nor that the children of the rich don’t necessarily have better lives than those brought up in poverty. Who knows which doors would be closed, even given her wealthy background, to someone named Blaptod (who refused, for private reasons, to change her name)? These children were not consulted when such a life-changing decision was made on their behalf. On the other hand, even without thereby attaining great wealth, people make such decisions affecting their children all the time (even if not quite so silly). They risk passing on inherited diseases, even horrible ones. They join communes where children are only barely tolerated. They take jobs which require them to move from place to place every year, or leave home for months at a time, or divorce on the flimsiest of pretexts. A silly name looks minor in comparison.

Sometimes, as in our example, they do odd things for the intended benefit of their children, even if the latter don’t understand why at the time. Recall the Johnny Cash song “A Boy Named Sue” (written by Shel Silverstein). The song’s narrator believes his life has been ruined by his maddeningly inappropriate name, and dedicates his life to finding the man who did this to him and paying him back in deadly fashion. But as that person notes when the confrontation arises, it was being forced to fight everyone who mocked his name that made Sue the focused and determined man he became. Maybe Crutbelg would learn to fight just as Sue did. On the other hand, if this guy with the weird name is filthy rich, maybe people would think twice about picking on him. But again, as with Sue, he might come to hate the person responsible. Is it worth the risk? Consider carefully, lest the eccentric djinn come upon you with his head-scratching offers while you are still unprepared to answer!

Addendum: A post at my old blog details some remarkable – indeed barely believable – examples of unusual naming, as culled from the book Freakonomics, which reveals as well that when we consider, as we did above, whether people are held back if they have weird and/or self-evidently minority (esp. black) names, the answer, when one controls for other factors, seems to be no. Still, I don’t think that’s going to be much consolation, during her childhood at least, to poor Blaptod.