by Tamuira Reid

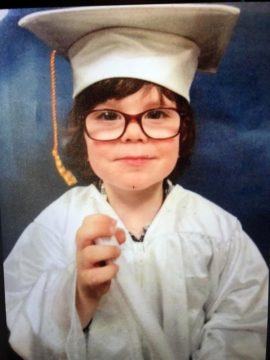

This is my son, Ollie.

This photo was taken five years ago. It’s one of my all-time favorites because of the look of absolute pride on his face. Hard-earned pride. I realize that pre-k graduation isn’t the most celebrated of milestones for a lot of families, but for us it was huge; Ollie was about to go mainstream.

Looking back at that little boy, and reflecting on the kid he is now, I feel lucky that we live in a city like New York. A city that has endless resources, creativity, spirit, hustle. The city that has taught us what it means to be humble, be grateful. A city that has afforded my disabled son access to an equal and appropriate education, and a public school with teachers who have loved and unconditionally supported him. A city that knows how to rally.

This is my son, Ollie.

Currently a proud in-coming fourth-grader, but with the same coke-bottle glasses and wide, generous smile. His backpack is usually absent-mindedly left open, and is stuffed with graphic novels, half-eaten bags of flaming hot Cheetos, a stress ball, and various contraband (slime, hotwheels cars, Skittles to share on the bus with potential friends, Pokemon cards to trade although he hasn’t figured out exactly how). As he passes you during drop-off, he will greet you with a “Good morning!”, maintaining direct eye contact, something that still feels, at times, unnatural to him.

Ollie Duffy doesn’t really walk from point A to point B, because the “electricity” running through his body, as he’d tell you, is hard to control. His movements are a little bit “more slippery” and unpredictable, like a sideways skip/grapevine type of thing, until he inevitably trips over his own feet. And even though he knows where he’s supposed to go, he often forgets mid-journey.

If Ollie sees your child crying, he will try to comfort them. Usually with a hug, sometimes with a Skittle. If that doesn’t work, he’ll sit nearby so they don’t feel alone. If Ollie is in class with a bully, he’ll feel sorry for them because being angry can mean you’re just frustrated, and he knows how that feels.

This is my son, Ollie.

Heart as big as the planet. Read more »

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

Covid has

Covid has  One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

Travelers to India came from all corners of the world through the ages for different reasons. The very first modern humans probably came there in order to escape harsh climate conditions elsewhere in the world. Latter day visitors arrived with varied objectives in mind. Some came seeking material fortune, some for spiritual enlightenment and others merely out of curiosity. A few who came, took what

Travelers to India came from all corners of the world through the ages for different reasons. The very first modern humans probably came there in order to escape harsh climate conditions elsewhere in the world. Latter day visitors arrived with varied objectives in mind. Some came seeking material fortune, some for spiritual enlightenment and others merely out of curiosity. A few who came, took what

—Change. Resilience. Where do we start? I’ve got no idea. What happens after this? Listen! The answer is here!—

—Change. Resilience. Where do we start? I’ve got no idea. What happens after this? Listen! The answer is here!— In 1940, at the height of Hitler’s invasion of Western Europe, Walter Benjamin, from Vichy France wrote, “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight.”

In 1940, at the height of Hitler’s invasion of Western Europe, Walter Benjamin, from Vichy France wrote, “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight.”

Mourning is in season. Newspapers of record these days publish interactive mass obituaries, images of “ordinary” people fallen to “the opioid crisis” or to Covid-19 (the front page of the Sunday New York Times was recently riven down the middle by a monolith composed of thousands of dots, growing denser towards the base, each representing a victim of the virus: the whole reminiscent of the graphic tributes to 9/11). The inauguration of the US president in January featured, in lieu of most spectators, ranks of flags, symbolizing the past year’s losses. The annual observation of International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Germany, held this year as for the past quarter century on January 27 at the Reichstag in Berlin, featured a remarkable ceremony marrying reconciliation with the starkest grief. In his latest book, the memoir-cum-poetics Inside Story, Martin Amis eschews his characteristic charades in a sincere and extended eulogy for Saul Bellow, Philip Larkin, and Christopher Hitchens, three of the central figures in the author’s professional and affective life. And, 15 years after it first appeared, The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion’s essay on death and bereavement, persists on various bestseller lists.

Mourning is in season. Newspapers of record these days publish interactive mass obituaries, images of “ordinary” people fallen to “the opioid crisis” or to Covid-19 (the front page of the Sunday New York Times was recently riven down the middle by a monolith composed of thousands of dots, growing denser towards the base, each representing a victim of the virus: the whole reminiscent of the graphic tributes to 9/11). The inauguration of the US president in January featured, in lieu of most spectators, ranks of flags, symbolizing the past year’s losses. The annual observation of International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Germany, held this year as for the past quarter century on January 27 at the Reichstag in Berlin, featured a remarkable ceremony marrying reconciliation with the starkest grief. In his latest book, the memoir-cum-poetics Inside Story, Martin Amis eschews his characteristic charades in a sincere and extended eulogy for Saul Bellow, Philip Larkin, and Christopher Hitchens, three of the central figures in the author’s professional and affective life. And, 15 years after it first appeared, The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion’s essay on death and bereavement, persists on various bestseller lists. Unfortunately, it is always worth your time to read a book in praise of the humanities. Given the unenviable position of the humanities in public education and in contemporary cultural and (especially) political discourse about valuable expertise, any author that comes to their defense has to find a strategy to shift the narrative, and will thereby almost invariably do something interesting.

Unfortunately, it is always worth your time to read a book in praise of the humanities. Given the unenviable position of the humanities in public education and in contemporary cultural and (especially) political discourse about valuable expertise, any author that comes to their defense has to find a strategy to shift the narrative, and will thereby almost invariably do something interesting.

Former Finnish President and

Former Finnish President and