by Mike O’Brien

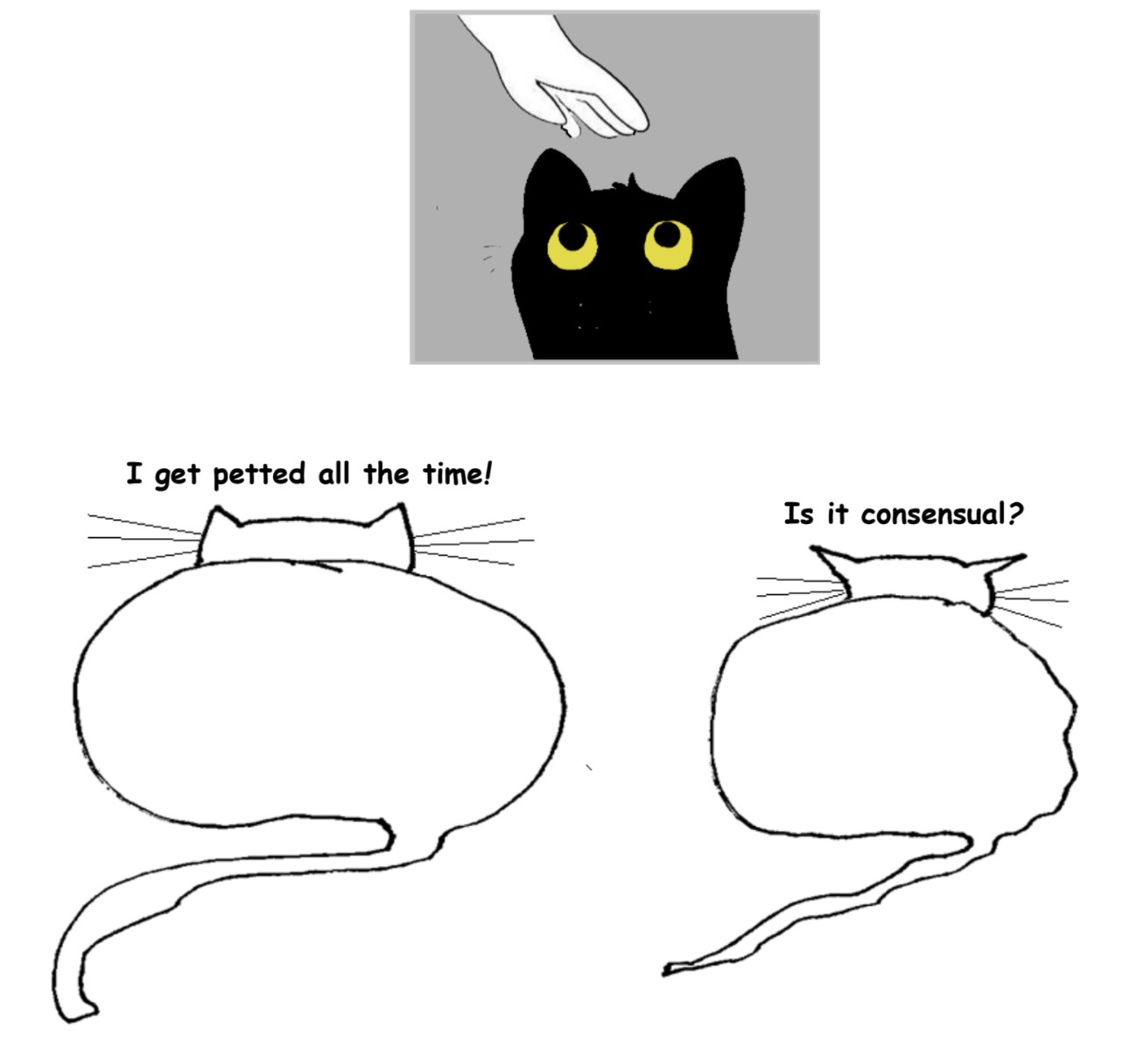

I heard a discussion about animal ethics recently, and the concept of “full moral standing” came up. The presumption was that we humans, certainly most of us and maybe even all of us, enjoyed this full moral standing, and the ethical quandary to be sorted was whether any other beings did as well. This is a common standpoint from which to philosophize about the rights and recognition due to our fellow earthlings: the view from the top. It is still quite common to assume that we are alone there. I suppose that this is a very sensible assumption, given the available data. Old modern myths, unfounded by anything except ignorance, arrogance and a deliberate withholding of curiosity about others’ experiences, denied animals any basis of consideration at all; no sensation, no consciousness, no “there” there at all. Increasing accumulation of knowledge, and decreasing self-delusion about the propriety of our collective abuse of nature, has lent more credibility to arguments for the moral enfranchisement of animals.

But facts only get you so far. When I was a wild and crazy youth, I pursued graduate philosophy studies and read a lot of works on sovereignty and the legitimacy of political power. One of the main take-aways of thousands of pages of obscure theory was the importance of make-believe. Not as a substitute for facts and logic, but rather as an accompanying dimension of thought. Even if humans are, in fact, completely determined in their behaviour by the laws of physics, the task of accurately predicting what billions of us will do decades hence is beyond our faculties. If we were simple enough to be predicted, we would be too simple to do the predicting. So, if we want to tell stories of what our collective future will look like, we have to make them up. The alternative is to be silent, and we are not the sort of apes to do that. Read more »

We think of AI as the stuff of science, but AIs are born artists. Those artistic talents are the key to their scientific power and their limitations.

We think of AI as the stuff of science, but AIs are born artists. Those artistic talents are the key to their scientific power and their limitations.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

Covid has

Covid has  One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?