Dear Rafiq,

I just received your new book of poems, “My Mother’s Scribe,” and was delighted to learn your mother’s name is Maryam.

My maternal grandmother was named Maryam. My mother (Araxie, ten-years old) last saw her and her 3 younger brothers in Urfa on the Death March in 1915. They were in bad shape. Presumed dead. Her father, Giragos, my maternal grandfather, was killed in their village before the Death March began. My paternal grandfather, Barsam, was killed in a massacre in 1895, when my father was born. Araxie ended up in an orphanage in Aleppo where she was from 1915-1921, when she went to Beirut, where she met and married my father.

By ship to France and another ship to New York where they lived for the next many decades at 521 E. 87th St, between York and East End. Father had a grocery store; we lived three flights up in a railroad flat. My father, Bedros, 80-years-old, was hit by a car at 87th and First Ave, just a block and a half from their apartment, in late January 1975. It was a Saturday. The car was driven by (I later learned) a Turkish doctor!

My father had escaped from the Turks in 1912 when he was 17. He reached New York in 1914. Some of his fellow Villagers—he was from Nibishi in Palu district, were already in New York. One of them was his brother-in-law, Kevork Garabedian. His wife, my father’s sister, Anna, was still in the “old country.” Bedros would not see her again until 1921 when they, including Araxie, all met in Beirut. Read more »

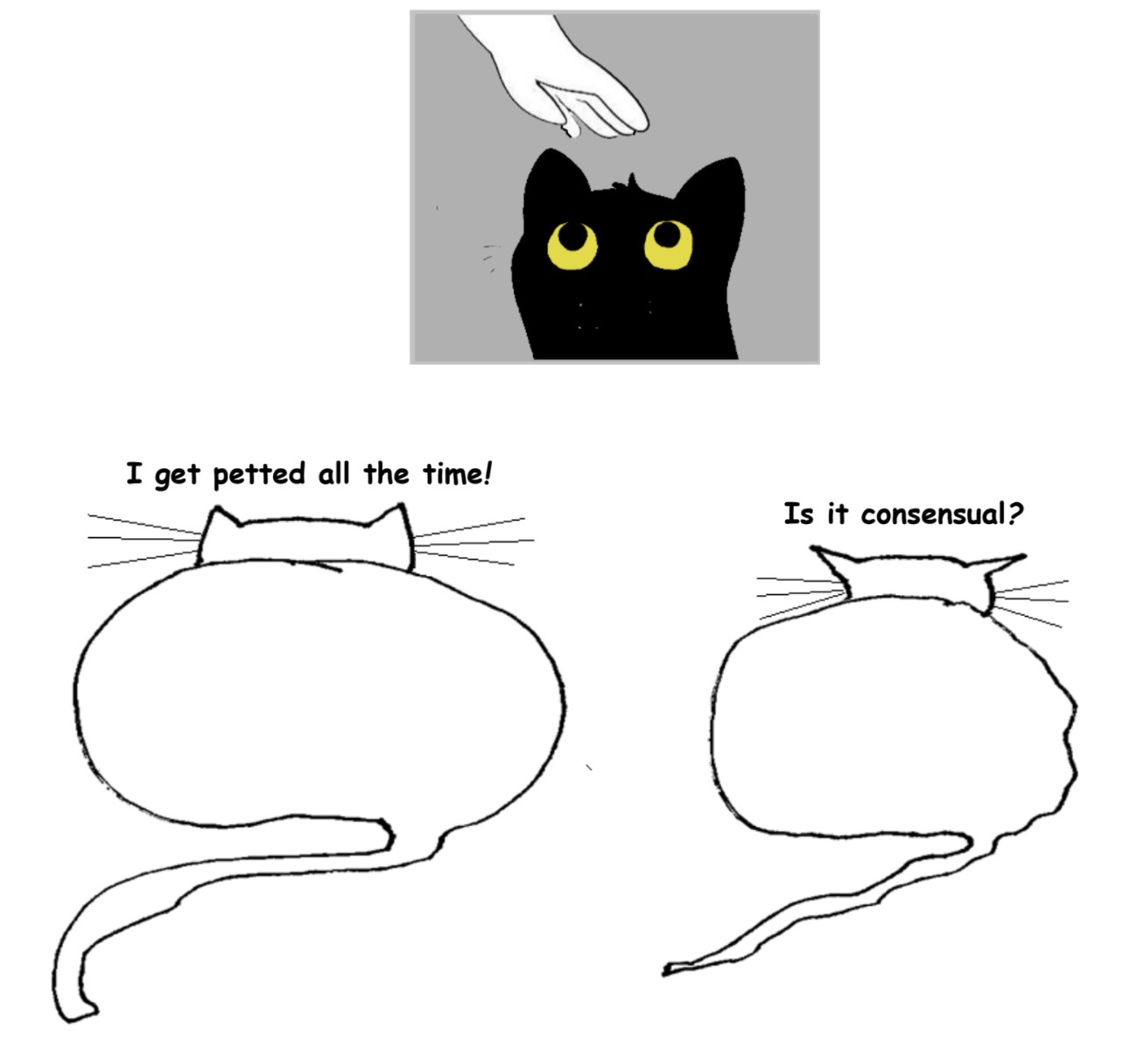

We think of AI as the stuff of science, but AIs are born artists. Those artistic talents are the key to their scientific power and their limitations.

We think of AI as the stuff of science, but AIs are born artists. Those artistic talents are the key to their scientific power and their limitations.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

Covid has

Covid has  One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

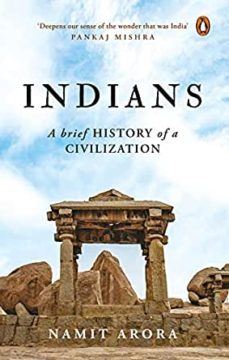

Travelers to India came from all corners of the world through the ages for different reasons. The very first modern humans probably came there in order to escape harsh climate conditions elsewhere in the world. Latter day visitors arrived with varied objectives in mind. Some came seeking material fortune, some for spiritual enlightenment and others merely out of curiosity. A few who came, took what

Travelers to India came from all corners of the world through the ages for different reasons. The very first modern humans probably came there in order to escape harsh climate conditions elsewhere in the world. Latter day visitors arrived with varied objectives in mind. Some came seeking material fortune, some for spiritual enlightenment and others merely out of curiosity. A few who came, took what