by Robyn Repko Waller

In April, many watched in awe as Elon Musk’s Neuralink demonstrated how Pager the rhesus monkey can play the video game Pong using only the power of thought. No bodily movements required. That is, he can control the virtual paddle with his mind. How? The researchers at Neuralink have fitted Pager with a brain-computer interface (BCI) — in this case, around 1000 fine-wire electrodes have been fitted onto Pager’s motor cortex via surgery. A decoding algorithm trains on neural activity data from Pager’s playing Pong the good old fashioned way, with a joystick. Later, the joystick is disconnected, and when Pager merely thinks about moving the paddle via the joystick in response to the virtual bouncing ball, the technology uses his decoded motor intentions to issue in digital commands to move the virtual paddle. (His reward for playing? A delicious smoothie.) He’s really good at Pong. So good that he’s been challenged to a game of Mind Pong by a human with a BCI.

Notably, such technology has been around in experimental and clinical settings for some time. To take another recent success, BCI has been used to produce text at a comparable speed to smartphone texting. A man who is paralyzed from the neck down was fitted with micro electrodes in his motor cortex. A recurrent neural network trained on neural activity data from the hand region of his premotor cortex while he imagined grasping a pencil and writing letters, a form of motor imagery. Using this method, the participant was able to “write” with minimal lag by imaging letters at the rate of ninety characters per minute with greater than 99% accuracy with autocorrect, a significant improvement over previous BCI feats of 40 characters per minute using point and click typing. Read more »

John Adams was not the kind of man who easily agreed, and it showed. Nor was he the kind of man who found others agreeable. Few have accomplished so much in life while gaining so little satisfaction from it. When you think about the Four Horsemen of Independence, it’s Washington in the lead, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and, last in the hearts of his countrymen, John Adams. You could add to that mix James Madison and even the intensely controversial Alexander Hamilton, and, once again, if you were counting fervent supporters, Adams would still bring up the rear.

John Adams was not the kind of man who easily agreed, and it showed. Nor was he the kind of man who found others agreeable. Few have accomplished so much in life while gaining so little satisfaction from it. When you think about the Four Horsemen of Independence, it’s Washington in the lead, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and, last in the hearts of his countrymen, John Adams. You could add to that mix James Madison and even the intensely controversial Alexander Hamilton, and, once again, if you were counting fervent supporters, Adams would still bring up the rear.

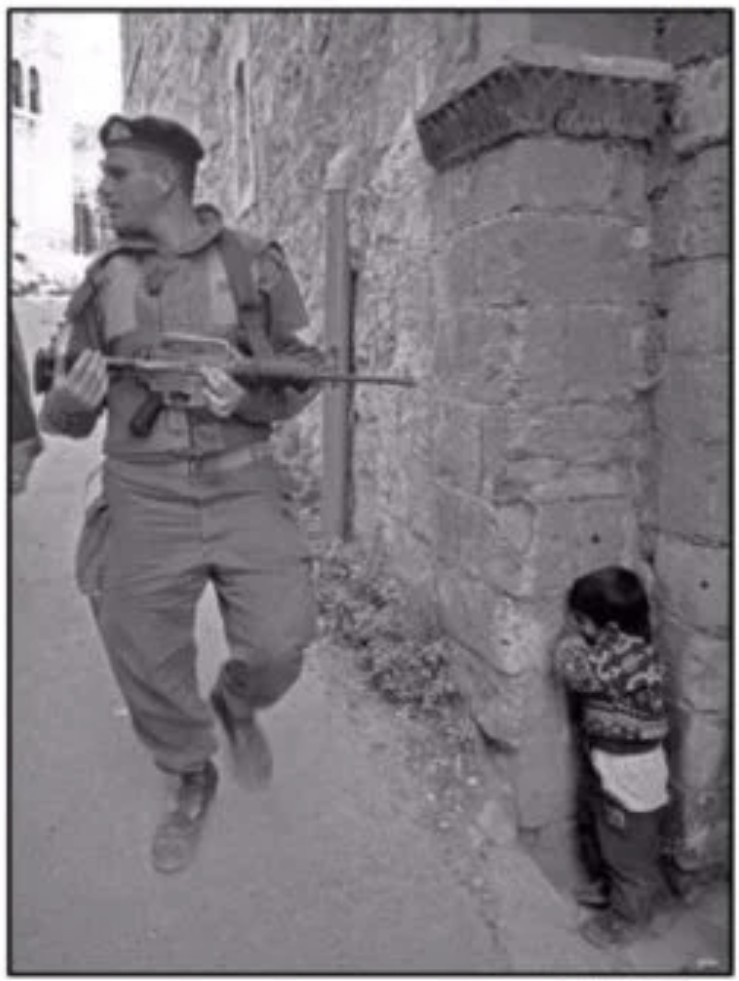

Shada Safadi. Promises. 2014.

Shada Safadi. Promises. 2014. The overwhelming majority of pre-service and in-service teachers I have worked with over the past two decades believe that they should, first and foremost, love, care, and nurture their students. Everything else associated with what is euphemistically called “best practice,” they believe, will follow. When pushed to describe what loving, caring and nurturing their students actually looks like within and beyond the classroom and school—in theory and practice—many of them have trouble getting beyond superficial appeals to “multiple intelligences,” “diversity,” “safe spaces,” and “culturally responsive pedagogy.” Focused primarily on making their students feel safe and emotionally supported, they’ve reduced their pedagogical responsibilities to a metaphorical big hug. Stir in a tablespoon of standardized ideological content, blend with a half cup of research-based strategies, add a pinch of job training/college prep, stir in a few high-stakes tests and, voilà, the neoliberal agenda for public education is rationalized and set.

The overwhelming majority of pre-service and in-service teachers I have worked with over the past two decades believe that they should, first and foremost, love, care, and nurture their students. Everything else associated with what is euphemistically called “best practice,” they believe, will follow. When pushed to describe what loving, caring and nurturing their students actually looks like within and beyond the classroom and school—in theory and practice—many of them have trouble getting beyond superficial appeals to “multiple intelligences,” “diversity,” “safe spaces,” and “culturally responsive pedagogy.” Focused primarily on making their students feel safe and emotionally supported, they’ve reduced their pedagogical responsibilities to a metaphorical big hug. Stir in a tablespoon of standardized ideological content, blend with a half cup of research-based strategies, add a pinch of job training/college prep, stir in a few high-stakes tests and, voilà, the neoliberal agenda for public education is rationalized and set.

Aye Chan Zin, a 22 year old competitive cyclist, once raced from Yangon to Mandalay and back. He fell and lost both incisors to gold teeth.

Aye Chan Zin, a 22 year old competitive cyclist, once raced from Yangon to Mandalay and back. He fell and lost both incisors to gold teeth.

For the past year or so there have been a considerable number of cases of teachers or authors or journalists who have been threatened with sanctions, had sanctions imposed, or lost their positions, because of articles they wrote or statements they made as part of their occupations. Many of these cases involved the appearance of the N-word in their speech or written work. Here are some of them.

For the past year or so there have been a considerable number of cases of teachers or authors or journalists who have been threatened with sanctions, had sanctions imposed, or lost their positions, because of articles they wrote or statements they made as part of their occupations. Many of these cases involved the appearance of the N-word in their speech or written work. Here are some of them. Please, See My Innocence

Please, See My Innocence Marine biologist Helen Scales’ book, The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed is a triumph. The four major sections in the book, ‘Explore’, ‘Depend’, ‘Exploit’ and ‘Preserve’ are indicators of the breadth of issues addressed in the book: the variety of life forms in the different levels of the oceans; the significance of the oceans to life on the planet; the various ways in which human activity exploits the oceans resources, and concludes with her ideas about how to prevent the ocean from becoming just another area of resources of the planet for exploitation by human beings.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ book, The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed is a triumph. The four major sections in the book, ‘Explore’, ‘Depend’, ‘Exploit’ and ‘Preserve’ are indicators of the breadth of issues addressed in the book: the variety of life forms in the different levels of the oceans; the significance of the oceans to life on the planet; the various ways in which human activity exploits the oceans resources, and concludes with her ideas about how to prevent the ocean from becoming just another area of resources of the planet for exploitation by human beings.