by Robyn Repko Waller

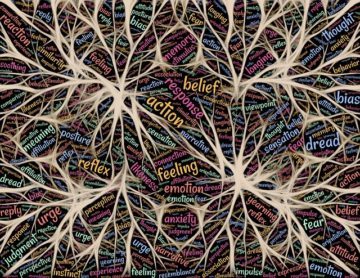

The case for the illusion of conscious agency from neuroscience is far from a straightforward conclusion.

Last month I introduced a curious disconnect in public perception of neurotechnology. Whereas reports of brain-computer interfaces (BCI) inspire celebration of expanding agency, the public seem wary that neuroimaging exposes the illusion of conscious agency. The curiosity being that both use neurotechnology to decode motor intentions from the same brain regions of interest. If one threatens our conscious control as human agents, doesn’t the other? If one is a celebration of human agential control, isn’t the other?

That is, I suggested there that, to the contrary, these like research programs ought to be treated alike. Either both applications of neurotechnology deal in diminished agency or, alternatively, neither does. I ended that discussion with a promissory note to defend my insistence that such research doesn’t threaten our control as agents. Here I’ll briefly outline the case, as it’s made, for the illusion of conscious will from neuroscience. Then I’ll argue why we ought to strike a more optimistic note about our scientific understanding of humans as acting consciously and freely (elsewhere I’ve laid out more detailed discussions of science of free will).

I’ve elaborated frequently in this column about the sense of agency and free will that most of us believe we enjoy. I’ll rehearse those important notions again here. The narrative of human agency is not simply that we act in goal-directed ways, actively affecting change beyond the impinging of happenings to us. Humans (and perhaps other complex animals) don’t just forage about locating resources or evading predators, or so we contend. It seems we exercise a much more meaningful kind of agency. That is, free will is not just that I control my bodily movements, but that I exercise meaningful control over what I decide to do. Read more »

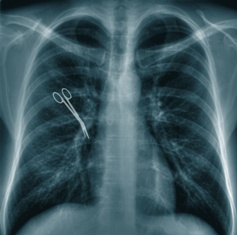

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

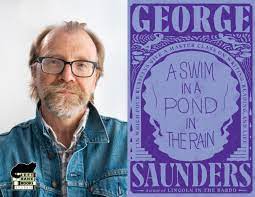

George Saunders’ recent book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the most enjoyable and enlightening book on literature I have ever read.

George Saunders’ recent book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the most enjoyable and enlightening book on literature I have ever read.

It seems as if everyone in the wine industry proclaims that wine tasting is subjective. Wine educators encourage consumers to trust their own palates. “There is no right or wrong when tasting wine,” I heard a salesperson say recently. “Don’t put much stock in what the critics say,” said a prominent winemaker to a large audience when discussing the aromas to be found in a wine. The point is endlessly promoted by wine writers. Wine tasting is wholly subjective. There is no right answer to what a wine tastes like and no standards of correctness for judging wine quality.

It seems as if everyone in the wine industry proclaims that wine tasting is subjective. Wine educators encourage consumers to trust their own palates. “There is no right or wrong when tasting wine,” I heard a salesperson say recently. “Don’t put much stock in what the critics say,” said a prominent winemaker to a large audience when discussing the aromas to be found in a wine. The point is endlessly promoted by wine writers. Wine tasting is wholly subjective. There is no right answer to what a wine tastes like and no standards of correctness for judging wine quality.

On February 18, 2021, NASA landed Perseverance rover on the surface of Mars. Perseverance is the latest of some twenty probes that NASA has sent to bring back detailed information about our neighboring planet, beginning with the Mariner spacecraft fly-by in 1965, which took the first closeup photograph. Though blurry by today’s standards, those grainy images helped ignite widespread wonder and fantasy about space exploration, not long before Star Trek also debuted on television. By the 1970s, science-fiction storytelling was moving from the margins of pop-culture into the mainstream in film and television—and so followed generations of kids, like myself, who grew up expecting off-world adventurism and alien encounters almost as much as we anticipated the invention of video-phones and pocket computers and household robots, as our conceptual bounds for the human story were pushed ever farther outward.

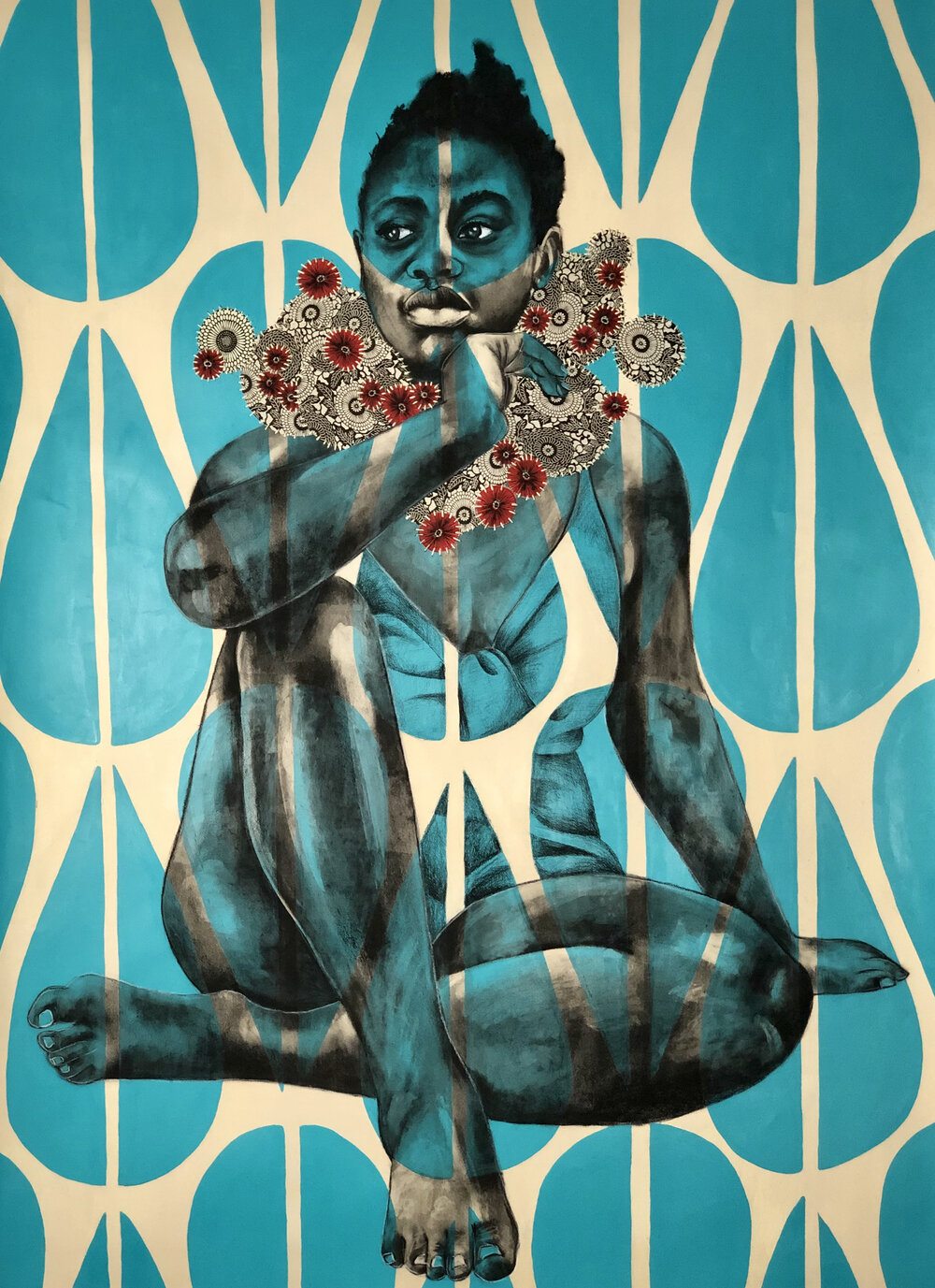

On February 18, 2021, NASA landed Perseverance rover on the surface of Mars. Perseverance is the latest of some twenty probes that NASA has sent to bring back detailed information about our neighboring planet, beginning with the Mariner spacecraft fly-by in 1965, which took the first closeup photograph. Though blurry by today’s standards, those grainy images helped ignite widespread wonder and fantasy about space exploration, not long before Star Trek also debuted on television. By the 1970s, science-fiction storytelling was moving from the margins of pop-culture into the mainstream in film and television—and so followed generations of kids, like myself, who grew up expecting off-world adventurism and alien encounters almost as much as we anticipated the invention of video-phones and pocket computers and household robots, as our conceptual bounds for the human story were pushed ever farther outward. Delita Martin. Rain Falls From The Lemon Tree. 2020

Delita Martin. Rain Falls From The Lemon Tree. 2020 It’s been 40 years this past month since the election of François Mitterrand as President of France. Today, June 21, is the day chosen by his first Minister of Culture for the

It’s been 40 years this past month since the election of François Mitterrand as President of France. Today, June 21, is the day chosen by his first Minister of Culture for the