by Joseph Shieber

Yeats composed his poem, “Among School Children”, after visiting St. Otteran’s School in Waterford in February, 1926, when Yeats was in his early 60s. It is probably best known for the couplet that concludes it: “O body swayed to music, O brightening glance,/ How can we know the dancer from the dance?” (Here is Helen Vendler leading a class on the poem at the Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, Harvard University, in 2007.)

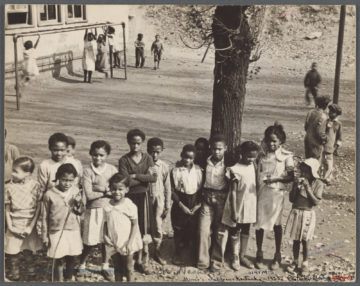

Read in its entirety, one of the major themes of its eight stanzas is the divergence between image and reality, and how humans suffer from attempting to privilege ideas over reality. In a note he wrote for himself in March, 1926, while composing the poem, Yeats describes the theme of the poem this way: “School children, and the thought that life will waste them, perhaps that no possible life can fulfill their own dreams or even their teacher’s hope.”

Despite the suggestion of Yeats’s own note, the poem doesn’t really deal with the dashed hopes of the students themselves. Instead, Yeats’s focus in the poem is on the illusions of the childrens’ mothers — and of the nuns who are their teachers.

For example, here is the seventh stanza:

Both nuns and mothers worship images,

But those the candles light are not as those

That animate a mother’s reveries,

But keep a marble or a bronze repose.

And yet they too break hearts—O Presences

That passion, piety or affection knows,

And that all heavenly glory symbolise—

O self-born mockers of man’s enterprise;

In previous stanzas, Yeats addresses the way in which a mother’s imagined future for her children doom her to disappointment when she compares those hopes against the reality of their lives. In the seventh stanza, Yeats turns to the expectations of the nuns who teach the children at the unnamed school of the poem — and at St. Otteran’s School, which inspired it.

Yeats suggests that the marble or bronze statues that are physical manifestations of the nuns’ love of “heavenly glory” will also “break hearts”. Those images, created by humans (“self-born”), will in the end also lead to disappointment (“mockers of man’s enterprise”).

Note Yeats’s unwillingness here to invest much belief in the objects of the “images” that the nuns “worship”. That is, in his description, they “worship images”, not God or Jesus or the saints themselves.

Given this, there’s an odd contrast between the illusions of the parents and nuns and the subject matter that the children learn in school. In the first stanza, Yeats writes that the “children learn to cipher and to sing,/ To study reading-books and history,/ To cut and sew, be neat in everything/ In the best modern way …” The implication here is that the illusory aspect of life “among school children” involves the expectations of the adults for the children’s future. There is no sense at all that the subjects that the children learn might also involve illusion, rather than reality.

This would seem to be a significant lacuna in Yeats’s musings in the poem. If “both nuns and mothers worship images”, surely they will pass on that worshipful attitude to their children. And if those images are misleading — “mockers of man’s enterprise” — surely the children will be misled by them no less than the adults.

Recent news and opinion coverage has been consumed with the myths and images that children learn about in school. Both those who embrace and those who decry the introduction of anti-racist curricula in schools have spilled a great deal of ink on this topic, with detractors lamenting the introduction of “Critical Race Theory” in classrooms and supporters welcoming changes that more accurately reflect both the country’s past and the experiences of its current crop of students, many of whom have seen countless images of repression against minority groups reproduced on social media.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the shallowness and banality of most public discourse, the debate between supporters and detractors of the discourse of anti-racism in schools has largely been characterized by an attempt to seize the mantle of truth against incursions of propaganda into the education system.

For example, in a recent piece for The Week entitled, “The left is anti-anti-Critical Race Theory”, Damon Linker pushes back on the idea that the outcry over so-called “Critical Race Theory” is merely being ginned up by Fox News (and other even more rightist media outlets). Instead, Linker argues, it is concerned parents who “do not want public schools propagandizing their children into becoming left-wing radicals. And it is perfectly reasonable for them to hold that position.”

As Linker sees it, “the effort to get schools to adopt assumptions derived from CRT for use in teaching history is itself a political act, an effort to prevail in a scholarly and civic dispute by seizing control of the means of knowledge production and dissemination.”

Supporters of the supposedly ascendant discourse of anti-racism might be excused for treating Linker’s description of the current outcry over CRT with a great deal of skepticism. When it comes to “seizing control of the means of knowledge production and dissemination”, it is conservative legislatures and conservative-controlled college and university boards that have tried to use the levers of political power to influence school curricula. Indeed, according to The New York Times, “more than 20 states including New Hampshire, Michigan, Texas and South Carolina have introduced legislation restricting teaching about race.” (You can now add my home state of Pennsylvania to that list.)

For example, consider the June 16 “Joint Statement on Legislative Efforts to Restrict Education about Racism and American History” signed by a number of learned societies, intellectual organizations, and associations in higher education, including the American Association of University Professors, the American Historical Association, the Association of American Colleges & Universities, and PEN America. The signatories of the Joint Statement decry “legislative efforts seek to substitute political mandates for the considered judgment of professional educators …” The signatories continue to argue that such “regulations constitute an inappropriate attempt to transfer responsibility for the evaluation of a curriculum and subject matter from educators to elected officials. … Politicians in a democratic society should not manipulate public school curricula to advance partisan or ideological aims.”

In seeing this debate as one in which the correct side — “our” side — is standing against an opposing force that seeks to “manipulate public school curricula to advance partisan or ideological aims” or “to prevail in a scholarly and civic dispute by seizing control of the means of knowledge production and dissemination”, both of these perspectives — those of the opponents of anti-racist discourse in public education as well as of the supporters — are flawed.

In fact, determining public school curricula always also involves “ideological aims,” as well as “control of the means of knowledge production and dissemination.” The AAUP and other learned organizations are correct in demanding that public school curricula be shaped by the “considered judgment of professional educators”. However, the statement by those organizations offers a false dichotomy.

The Joint Statement contrasts “the considered judgment of professional educators” with the “partisan or ideological aims” of “politicians”. This ignores two aspects of the shaping of educational curricula that shouldn’t be elided.

First, in a democratic society, experts have to convince the public that their expertise is worth acknowledging. This is requires political engagement. So, while it is fine to assert that we should design curricula according to “the considered judgment of professional educators”, it would be even better to give reasons why this is the case — the more concrete, the better.

Second, we shouldn’t ignore the fact that professional educators’ considered judgments might themselves involve “ideological aims.” Anti-racism is also an ideology. Given this, the contest is not between pure facts, on the one side, and ideology, on the other, but between multiple competing ideologies.

One of the few essays subtle enough to note the failings inherent in both sides’ attempt to claim the imprimatur of factuality in this debate is Matthew Karp’s striking essay in Harper’s, “History as End”. There, Karp suggests that both the supporters of anti-racism — represented by the 1619 Project — and their opponents — represented by the Trump Administration’s slapdash 1776 Report — share a focus on historical origins that distorts history in ways that make it ill-suited to the problems that face us now.

Karp criticizes both strands as “origins-obsessed” history:

Whatever birthday it chooses to commemorate, origins-obsessed history faces a debilitating intellectual problem: it cannot explain historical change. A triumphant celebration of 1776 as the basis of American freedom stumbles right out of the gate—it cannot describe how this splendid new republic quickly became the largest slave society in the Western Hemisphere. A history that draws a straight line forward from 1619, meanwhile, cannot explain how that same American slave society was shattered at the peak of its wealth and power—a process of emancipation whose rapidity, violence, and radicalism have been rivaled only by the Haitian Revolution. This approach to the past, as the scholar Steven Hahn has written, risks becoming a “history without history,” deaf to shifts in power both loud and quiet.

In contrast to “origins-obsessed” history, Karp suggests that we follow Frederick Douglass in recognizing that history is a battleground on which we steer the course of our activities now:

Douglass questioned the wisdom of any historical politics that undermined the prospects for present-day change. This did not imply a purely instrumental contempt for the past, in the manner of the Trumpian right, but rather reflected a clear-eyed determination to treat history not as scripture or DNA, but as a site of struggle. “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future,” Douglass declared. “To all inspiring motives, to noble deeds which can be gained from the past, we are welcome. But now is the time, the important time.” For some scholars, this must read like rank presentism—yet unlike the neo-originalist framing of the 1619 Project, it gets the order of operations right.

The past may live inside the present, but it does not govern our growth. However sordid or sublime, our origins are not our destinies; our daily journey into the future is not fixed by moral arcs or genetic instructions. We must come to see history, as [the theorist Wendy] Brown https://polisci.berkeley.edu/people/person/wendy-brown put it, not as “what we dwell in, are propelled by, or are determined by,” but rather as “what we fight over, fight for, and aspire to honor in our practices of justice.” History is not the end; it is only one more battleground where we must meet the vast demands of the ever-living now.

To return to the framing of the debate between Damon Linker and the signatories of the Joint Statement, to say (in Karp’s phrase) that history is a “site of struggle” is to recognize that its use in the public sphere is always political and ideological. (Another illustration sensitive to the fact this is a debate between rival ideologies, rather than between ideology and unadulterated fact, is the discussion between Aaron Hanna and Glenn Loury on the limitations of Black conservative thought in Quillette.)

This is not to say that facts don’t matter when it comes to history — they do. Nor is it to say that “both sides” of this debate are on equal footing when it comes to respect for the facts, for professional academic norms, or for open inquiry.

It is to say that even when both sides of a debate do respect the facts, observe professional norms, and embrace open inquiry, there will still be room for metaphors and unquestioned first principles in shaping their positions. These are the spaces in which ideology flourishes. These are the openings for political negotiation, if a consensus is to be found, or for political struggle, if consensus is impossible.