by Carol A Westbrook

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

I am often asked why I chose oncology. Many people fear cancer, and do not even like talking about it. How can you deal with all the pain and death, I am asked.

My answer is straightforward–it’s the patients. I enjoy working with cancer patients. They are some of the bravest people you will ever meet. And they are honest. There are no malingerers in cancer. When a cancer patient complains about a stomachache, headache, nausea, or worsening pain, you can be sure it’s real. It is so gratifying to me, as a doctor, to provide a patient some relief, some hope, and even, sometimes, a cure. And they all have a story to tell, if you take the time to listen.

And we had the time, back in those days. Medicine was not as rushed as it is today, in the race to get patients through the clinic visit quickly, as it is today. The clinic visits were often a half hour or more, because we oncologists took over the role as their internists, managing their diabetes, hypertension, depression, and just about any other problem that today would get referred to their primary care physician or a specialist.

Medical Oncology was a relatively young field. Oncology certification–medical oncology boards–had only been offered for the first time in 1974. Prior to that time, cancer was treated by surgeons. The field of medical oncology developed when we began to treat cancer with medicines instead of surgery. At the beginning we only had a few medicines that could work on cancer. Some of these came out of post-WWII research, like Nitrogen Mustard, derived from poison mustard gas, which gave remarkable remissions and even cures in Hodgkin’s’ disease. Or adriamycin, developed as an antibiotic, which proved to be very bad at killing bacteria, but very effective at killing cancer cells. With these few medicines we treated cancer, and tested new cancer drugs as they became available.

Medical Oncology was a relatively young field. Oncology certification–medical oncology boards–had only been offered for the first time in 1974. Prior to that time, cancer was treated by surgeons. The field of medical oncology developed when we began to treat cancer with medicines instead of surgery. At the beginning we only had a few medicines that could work on cancer. Some of these came out of post-WWII research, like Nitrogen Mustard, derived from poison mustard gas, which gave remarkable remissions and even cures in Hodgkin’s’ disease. Or adriamycin, developed as an antibiotic, which proved to be very bad at killing bacteria, but very effective at killing cancer cells. With these few medicines we treated cancer, and tested new cancer drugs as they became available.

In those days, we had few remedies for the side-effect of cancer treatment, such as diarrhea and nausea. Yet these brave patients chose to undergo medical treatment of their cancer and put up with these side effects. The reason was the hope of a cure, or prolongation of their life at the very least. Oncologists gave them this hope, and a listening ear. And they joined clinical trials as a way to help future cancer patients, and a chance at a drug that might be a miracle cure.

On occasion a patient in a clinical trial would strike it rich.

Take, for example, Hairy Cell Leukemia. This blood cancer caused an enlarged spleen and low blood counts; there were no treatments in the early 1980’s, and it was fatal within 2 years. Many cancer drugs were tested which had no effect, until interferon became available. Most of my patients got complete remissions, and many were cured indefinitely. One of them told me that he was prepared for death, and I brought him back to life! Imagine how gratifying it is for us, the doctor, to be able to offer a curative drug, to rescue a patient from certain death.

We also had cis-platinum, which could cure testicular cancer, a cancer that usually struck down men in the prime of their life. Cis-platinum was effective, and usually curative in early stages of the cancer. However, it caused the most nausea of any drug I have ever given! Yet it was not a difficult choice–put up with the side effects in hopes of a cure.

I recall a 19-year-old man to whom we were giving Cis-platinum chemotherapy. This man joined a clinical trial testing whether nausea from chemo could be relieved by smoking marijuana.

Marijuana was illegal in the 80’s, so the marijuana we tested was carefully regulated. It was supplied by the National Cancer Institute in the form of rolled joints, which were kept under lock and key. He was lucky in this trial, too. He was the only one of our patients in which the joints got rid of his nausea. He was “high” throughout all the chemo treatments. Most of the other patients, especially older adults, did not like the marijuana, and it did not provide relief of the nausea. He asked if he could continue his marijuana treatment after the cancer was gone, but his request was not approved. Today we have much better anti-nausea medications, but marijuana remains an unofficial drug for many, and is finally gaining acceptance, 40 years later.

Not everyone was so lucky. One of the most colorful characters I met was an elderly man, a veteran, who was in residence at the VA hospital. He had leukemia that was not responding to any treatment, and there was nothing more to do. Technically speaking, he was not a patient of mine, but our research group was studying his cancer cells. We wanted to get another sample before he died. I went to ask his permission to draw some blood. (In those days we were quite lax about patient confidentiality, IRB approval, and written permissions.)

He was delighted to have a visitor. He was in great humor, and had many stories to tell. He joked about his leukemia. When his leukemia cells came back, he said his doctor told him not to buy any long-playing records! And his insurance agent sent him only a 3-month calendar this year! He went on and on, and we laughed and joked for hours.

He admitted he was not afraid of dying after facing war on two fronts. He graciously let me draw his blood. “Anything to help leukemia research,” he said. “Come back again.” I didn’t, though, because he died a few weeks later.

He admitted he was not afraid of dying after facing war on two fronts. He graciously let me draw his blood. “Anything to help leukemia research,” he said. “Come back again.” I didn’t, though, because he died a few weeks later.

The hardest part of my job was to tell a patient that the treatments weren’t working, and there was nothing more to do but stop treatment. I was assigned to Jim, a 40-year-old man in the hospital with prostate cancer who was failing all treatment. During his hospital stay, he was always surrounded by family members, many of whom camped in in reception room and spoke a foreign language. They told me it was Romanian.

After reviewing the chart, I had a frank discussion with Jim. I suggested that he stop all treatment and be discharged, to spend his lasts few days with his family. He said he would only make his decision when he discussed it with his uncle. His uncle was flying in, and arrived with his entourage a few days later. Uncle was an imposing man, treated with deference by everyone in the family. He listened politely to my evaluation, and then dismissed me and went to confer with the Jim and his family.

After he left, Jim called me in.

“Uncle said it was okay to stop all treatment, so please discharge me as soon as possible.”

“What are you going to do?” I asked.

“Drink a bottle of wine, and then head to Vegas. I’m feeling lucky,” he answered. He was anything but lucky, I thought.

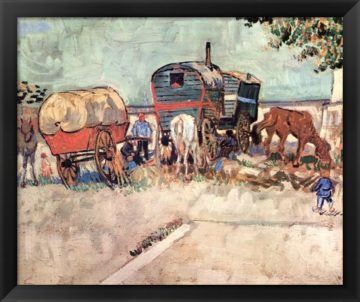

I realized then that the Gypsy King actually exists, and I was lucky enough to meet him.

I was caring for one patient with metastatic kidney cancer; he had a large, painful tumor in his chest, behind the bones. The cancer was stable, did not increase in size, but did not shrink with chemo, either. It was extremely painful, and he could only control it with narcotics. In Pennsylvania, our laws required that narcotics could only be given on a 1-month prescription which had to be written and delivered to the pharmacy in person. So my patient drove 35 miles each way over a winding mountain road to my clinic every month to get his prescription.

One of my favorite patients was a little old lady, Mrs. Zielinski (not her real name). She had recurrent Hodgkin’s disease, and we battled through the better part of a year, trying to keep her comfortable and hoping for a remission. I saw her frequently. Once she missed a visit, but returned to the clinic a few weeks later. She said she had been hospitalized in intensive care with pneumonia. The Intensive Care Unit staff didn’t bother to inform me about it. She looked remarkably well for someone who was on the brink of death for a week, on a respirator. She only complained about some chest pain.

“When did the chest pain start?” I asked, concerned that she might have some cardiac disease.

“I first noticed it the day after my cardiac arrest.”

“What?!! You had a cardiac arrest and they didn’t even notify me, your doctor?”

“Well I survived, I don’t remember much, but they did pound on my chest.”

“That explains your chest pain,” I said, “They cracked a few ribs. Nothing to do except take some Ibuprofen, the ribs will heal in about 1 or 2 weeks.”

Poor Mrs. Zielinski! She was battling Hodgkin’s disease, and all she wanted was to make it to her granddaughter’s wedding next summer. Then another complication came up—she was diagnosed with AIDS, which she had caught from a blood transfusion for emergency surgery year ago. In the 1980’s AIDS was a death sentence, as bad as any cancer. She was in tears when she found out. “I never did anything with anyone else except my husband. Everyone will think I’m a homosexual.” I reassured her that it was neither her nor her husbands’ fault.  We managed her as well as we could, and she made it to the wedding. She died shortly thereafter from AIDS.

We managed her as well as we could, and she made it to the wedding. She died shortly thereafter from AIDS.

I took care of an elderly woman, unmarried, who lived with two maiden sisters. The sisters brought her in because the big lesion her left breast was getting bigger and starting to ooze and smell funny. I wondered how it could progress for so long without her seeking medical attention, and the patient answered that it was not painful, but she was too blind to see it in the mirror. When I examined her, I found she had very dense cataracts over both eyes. And it took only a quick look to realize that she had invasive breast cancer.

At that first visit, I ordered her imaging studies to evaluate her stage, sent her to a surgeon for a biopsy, and referred her to an ophthalmologist. The bad news came back from the imaging studies and the biopsy report: she had stage 4, metastatic breast cancer. The good news was from the ophthalmologist, who was confident that she could restore the patient’s vision with simple cataract surgery. Within a week she could see again, for the first time in 5 years! She was so pleased that she could see her sisters and her nieces and nephews and grand-nieces and -nephews!

She initially had a good response to treatment, but in a few months her cancer recurred. After some months of trying various chemo regimens, she was advised to stop treatment. At her last clinic visit she said goodbye. She was resigned to dying soon of breast cancer, but she thanked me for referring her to cataract surgery. “Thank you for giving me my vision back, for making my last few months so wonderful!”

It was one of the best thanks that I ever got from a patient.

In those early days of oncology, we managed the side effects of drugs and cancer pain, and we held our patients’ hands, and listened to their stories. We became good friends. The hard part was when treatment failed, and we managed their care until death.

Nowadays, when treatment is stopped, we ship the patient to a hospice service and move on to the next case. It is more cost-effective and it frees up the oncologist to see patients who need treatment, but I find it cold-blooded, and it is not a compassionate way to treat a dying patient.

In retrospect, hospice care was the first step in turning cancer care into a business. The transition was gradual, and I’m not about to wax eloquent about the economics of health care. Many books and articles have been written on this topic, and my amateur analysis will be naive. Suffice it to say that the business side of the healthcare system began to have a larger say in how we practiced medicine. The hospital and clinical administrators controlled our facilities, our reimbursements, our nursing staff, and, in many cases, our salaries, so we had little say in reversing this process. But my perspective was that the purpose of healthcare had changed from providing care to patients to generating income.

No longer was cancer care defined as an individual doctor treating a patient with cancer. Today, the cancer patient is treated by a healthcare system, which includes doctors, nurses, nurse specialists, pharmacists, social workers, etc. As Nick Adams, MD, MBA, the medical economist wrote, “Healthcare organizes doctors and patients into a system where that relationship can be financially exploited and as much money extracted as often as possible by hospitals, clinics, health insurers, the pharmaceutical industry, and medical device manufacturers.”

Spending time with a patient to listen to their story, alleviate their cancer symptoms, and befriend them, was gratifying to us, the doctors. It’s what keeps us going, the reason why we became physicians in the first place. Trying to squeeze these old-fashioned medical practices into the modern healthcare model, with its emphasis on seeing as many patients as possible as quickly as possible, was a frustrating experience. We were just cogs in a wheel. It led to burnout in many of us. I finally succumbed in 2017 and quit clinical medicine. I still miss practicing oncology, and all the wonderful people I got to know.

Take for example, this elderly lady with colon cancer. We became good friends, but then her treatment stopped working and she knew she knew there was nothing more that I could do for her. She went into hospice care. A few days later the hospice nurse called me to tell me that the patient asked me to visit her. In all my years of practice I had never made a house call! But this time, I stopped by on my way home from work.

She lived by herself in a small house in a senior development, a tidy little place that was filled with flowers and pictures and hand-knitted items. “I’m happy to see you,” she said. “I missed you; I missed our little talks at the clinic visits. I wanted to say good-bye, and wanted to thank you for being a friend to me.”

I promised her I’ll always remember her. She died a few days later, but I still think of her often, the brave little lady facing death, holding my hand and saying good bye. My cancer patient.

This blog is dedicated to all my cancer patients, so they will never be forgotten.

citation:

Nick T. Sawyer, MD, MBA. In the U.S. “Healthcare” Is Now Strictly a Business Term. West J Emerg Med. 2018 May; 19(3): 494–495.