by Tim Sommers

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such debate. If so, you’re not wrong. But I think it’s still worth asking, ‘Why is so much anger, seemingly out of nowhere, suddenly directed against this obscure academic subfield called Critical Race Theory?’

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such debate. If so, you’re not wrong. But I think it’s still worth asking, ‘Why is so much anger, seemingly out of nowhere, suddenly directed against this obscure academic subfield called Critical Race Theory?’

Critical Race Theory came out of a law school movement called Critical Legal Studies in the late 70s and early 80s. The key ideas that connected CRT to CLS were that (i) the law is much less coherent and much more indeterminate than scholars, judges, and lawyers like to admit. (ii) This indeterminacy both obscures and abets the laws’ real purpose, which is to protect the interests of those who created and enforce it. (iii) The law is racist, therefore, but how it is racist is not always obvious, and that’s the most important question. And so (iv) we should be more concerned with systematic, institutional racism than the fact that individual people hold racist beliefs or attitudes.

In response to the recent controversy, some academics have reacted by saying that this is all that there is to CRT and that we should distinguish CRT from (for example) Critical Race Studies – which is essentially CRT outside of law schools. I don’t think that before this debate started, however, many people would have drawn a sharp line between CRT and CRS. Nor is it quite accurate, I think, to say that this is all that there is to CRT. In my experience, CRT has come to be used in academia as shorthand for the view that (i) racism is a big problem in America and that (ii) that problem is more of a systemic, institutional one – than a problem about specific individuals having racists attitudes and beliefs. Read more »

Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable.

Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable. A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

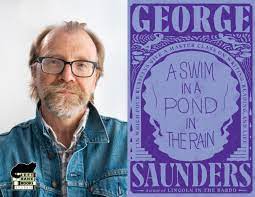

George Saunders’ recent book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the most enjoyable and enlightening book on literature I have ever read.

George Saunders’ recent book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the most enjoyable and enlightening book on literature I have ever read.